I began my first day in Kissingen with a stroll in the grounds of the spa. The ducks were still asleep on the lawn, the white down of the poplars was drifting in the air, and a few early bathers were wandering along the sandy paths like lost souls. Without exception, these people out taking their painfully slow morning constitutionals were of pensioner age, and I began to fear that I would be condemned to spend the rest of my life amongst the patrons of Kissingen, who were in all likelihood preoccupied first and foremost with the state of their bowels. Later I sat in a cafe, again surrounded by elderly people, reading the Kissingen newspaper, the Saale-Zeitung. The quote of the day, in the so-called Calendar column, was from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and read: Our world is a cracked bell that no longer sounds. It was the 25th of June. According to the paper, there was a crescent moon and the anniversary of the birth of Ingeborg Bachmann, the Austrian poet, and of the English writer George Orwell. Other dead birthday boys whom the newspaper remembered were the aircraft builder Willy Messerschmidt (1898–1978), the rocket pioneer Hermann Oberath (1894–1990), and the East German author Hans Marchwitza (1890–1965). The death announcements, headed Totentafel, included that of retired master butcher Michael Schultheis of Steinach (80). He was extremely popular. He was a staunch member of the Blue Cloud Smokers' Club and the Reservists' Association. He spent most of his leisure time with his loyal alsatian, Prinz. -

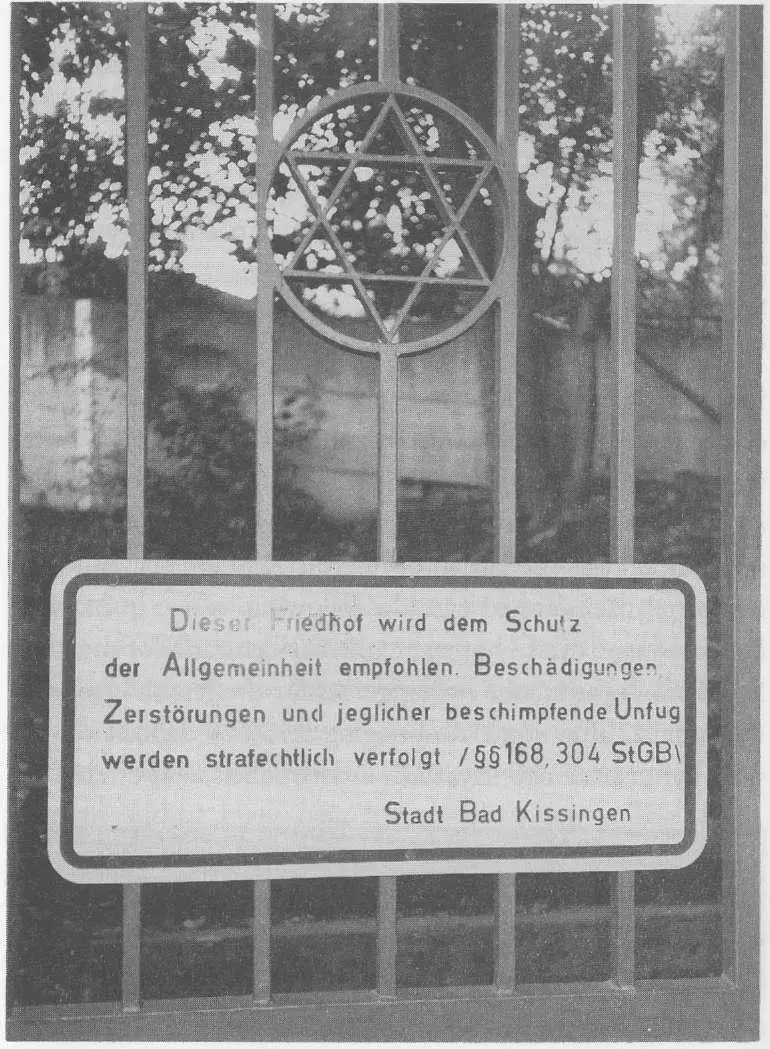

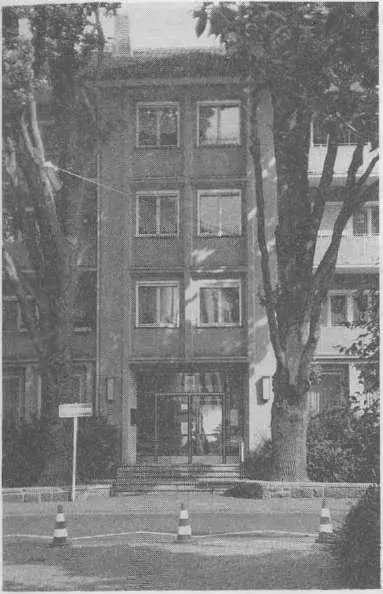

Pondering the peculiar sense of history apparent in such notices, I went to the town hall. There, after being referred elsewhere several times and getting an insight into the perpetual peace that pervades the corridors of small-town council chambers, I finally ended up with a panic-stricken bureaucrat in a particularly remote office, who listened with incredulity to what I had to say and then explained where the synagogue had been and where I would find the Jewish cemetery. The earlier temple had been replaced by what was known as the new synagogue, a ponderous turn-of-the-century building in a curiously orientalized, neo-romanesque style, which was vandalized during the Kristallnacht and then completely demolished over the following weeks. In its place in Maxstrasse, directly opposite the back entrance of the town hall, is now the labour exchange. As for the Jewish cemetery, the official, after some rummaging in a key deposit on the wall, handed me two keys with orderly labels, and offered me

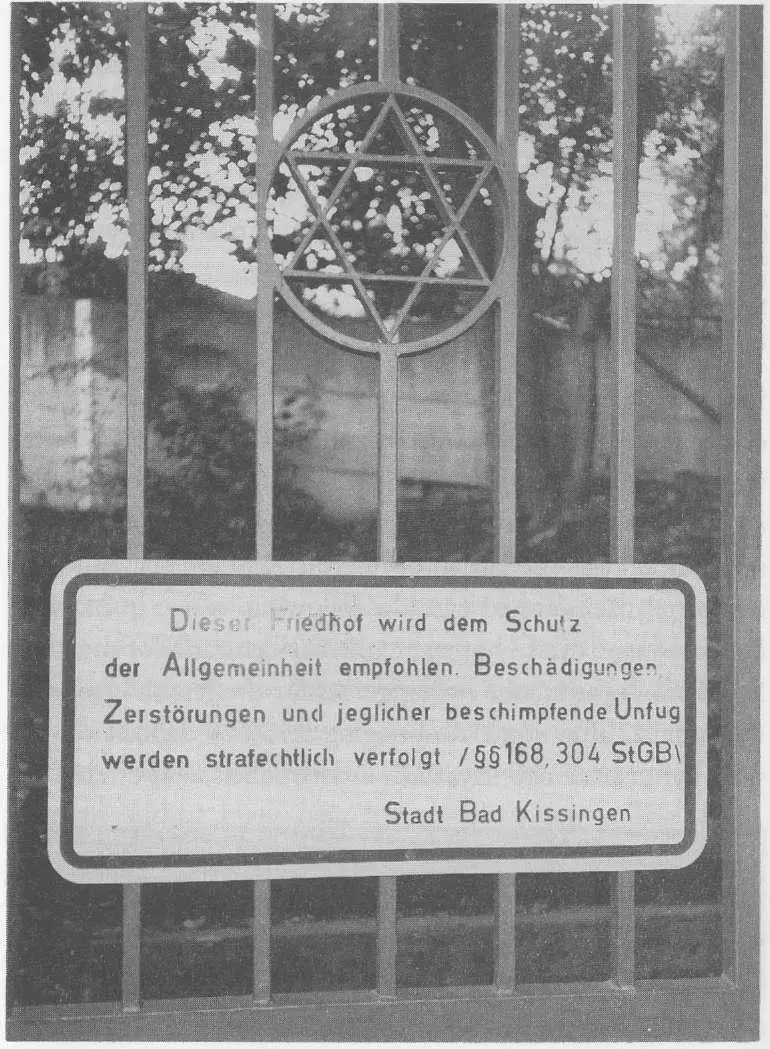

the following somewhat idiosyncratic directions: you will find the Israelite cemetery if you proceed southwards in a straight line from the town hall for a thousand paces till you get to the end of Bergmannstrasse. When I reached the gate it turned out that neither of the keys fitted the lock, so I climbed the

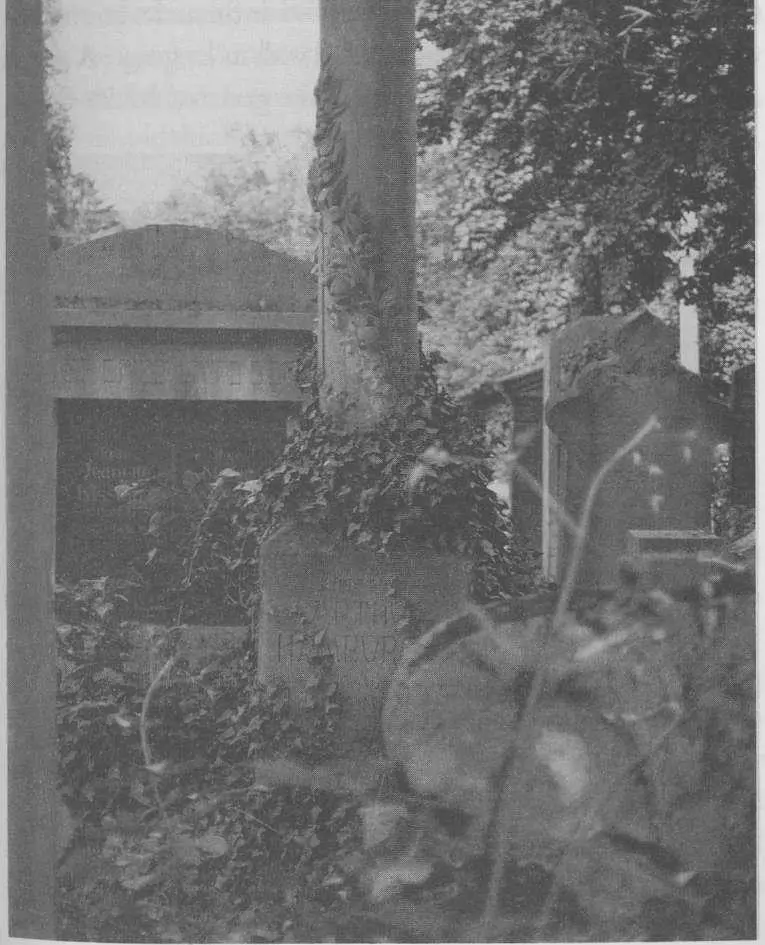

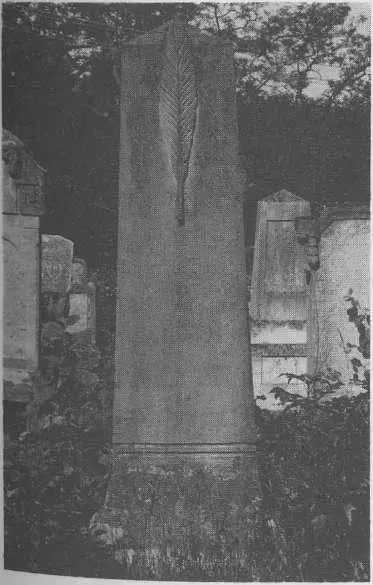

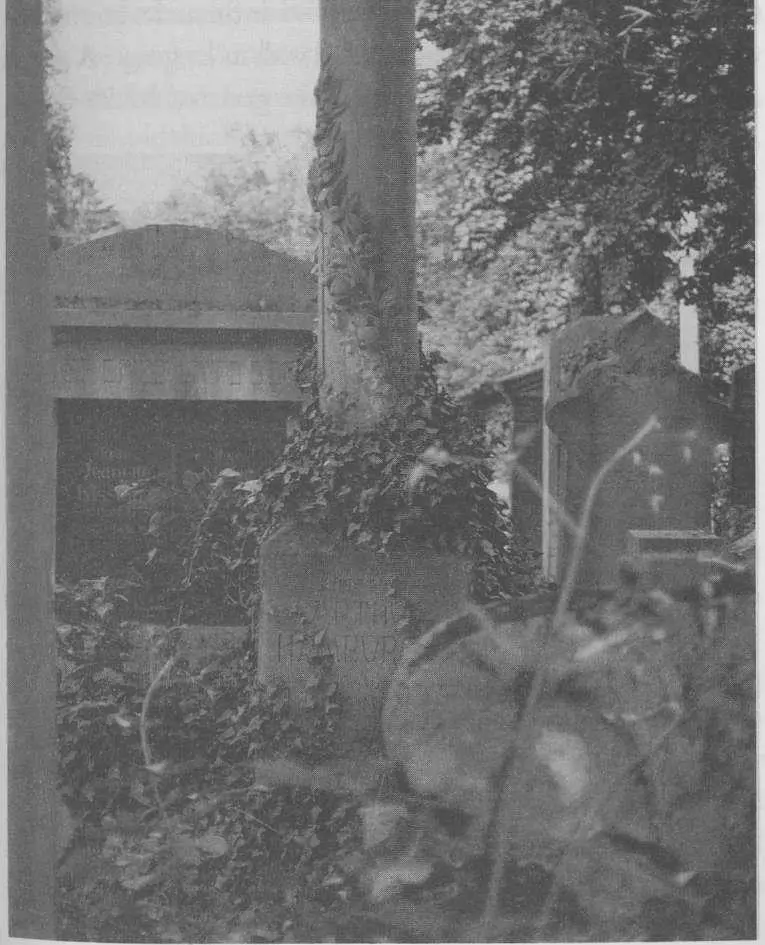

wall- What I saw had little to do with cemeteries as one thinks of them; instead, before me lay a wilderness of graves, neglected for years, crumbling and gradually sinking into the ground amidst tall grass and wild flowers under the shade of trees, which trembled in the slight movement of the air. Here

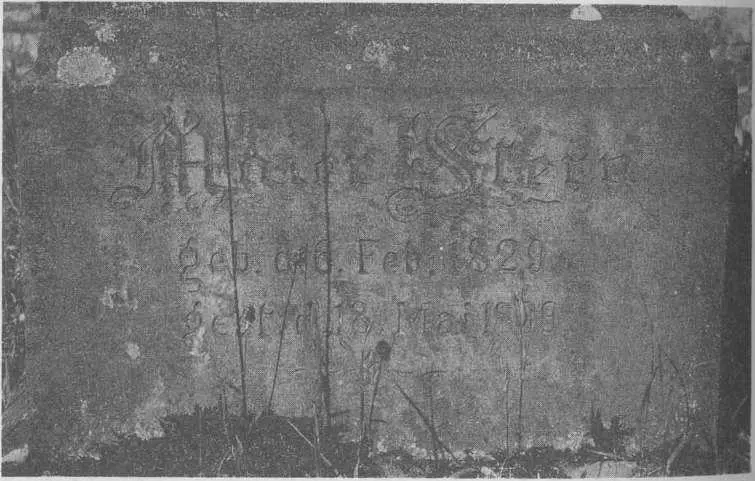

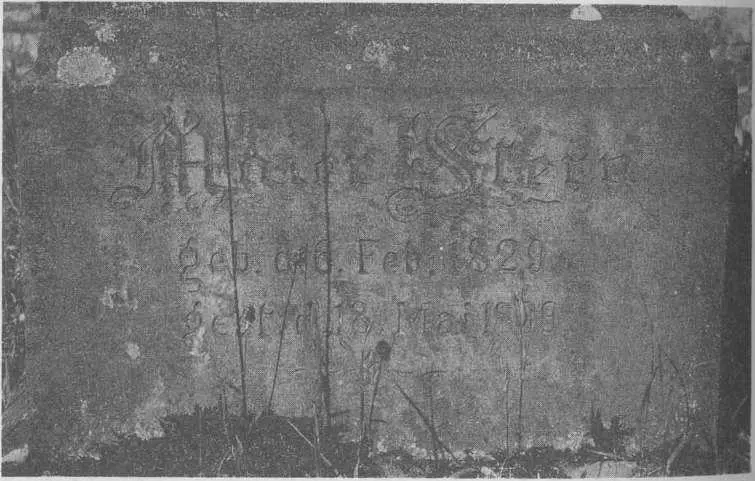

and there a stone placed on the top of a grave witnessed that someone must have visited one of the dead — who could say how long ago. It was not possible to decipher all of the chiselled inscriptions, but the names I could still read — Hamburger, Kissinger, Wertheimer, Friedlànder, Arnsberg, Auerbach, Grunwald, Leuthhold, Seeligmann, Frank, Hertz, Goldstaub, Baumblatt and Blumenthal — made me think that perhaps there was nothing the Germans begrudged the Jews so much as their beautiful names, so intimately bound up with the country they lived in and with its language. A shock of recognition shot through me at the grave of Maier Sterm,

who died on the 18th of May, my own birthday; and I was touched, in a way I knew I could never quite fathom, by the symbol of the writer's quill on the stone of Friederike Halbleib, who departed this life on the 28th of March 1912-I imagined her pen in hand, all by herself, bent with bated breath over her work; and now, as I write these lines, it feels as if / had lost her, and as if / could not get over the los. 1despite the many years that have passed since her departure. I stayed in the Jewish cemetery till the afternoon, walking up and down the rows of graves, reading the names of the dead, but it was only when I was about to leave that I discovered a more recent gravestone, not far from the locked gate, on which were the names of Lily and Lazarus Lanzberg, and of Fritz and Luisa Ferber. I assume Ferber's Uncle Leo had had it erected there. The inscription says that Lazarus Lanzberg died in Theresienstadt in 1942, and that Fritz and Luisa were deported, their fate unknown, in November 1941. Only Lily, who took her own life, lies in that grave. I stood before it for some time, not knowing what I should think; but before I left I placed a stone on the grave, according to custom.

Although I was amply occupied, during my several days in Kissingen and in Steinach (which retained not the slightest trace of its former character), with my research and with __the writing itself, which,

as always, was going laboriously, I felt increasingly that the mental impoverishment and lack of memory that marked the Germans, and the efficiency with which they had cleaned everything up, were beginning to affect my head and my nerves. I therefore decided to leave sooner than I had planned, a decision which was the easier to take since

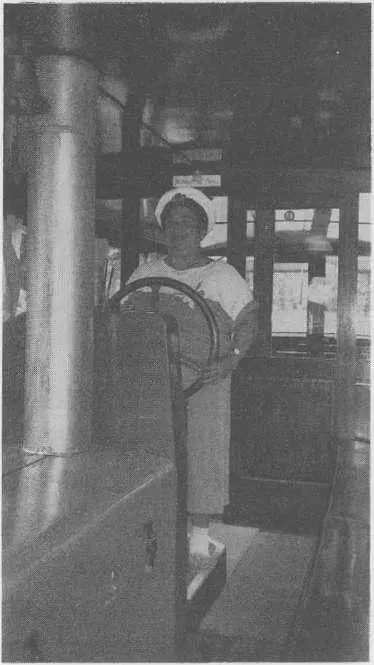

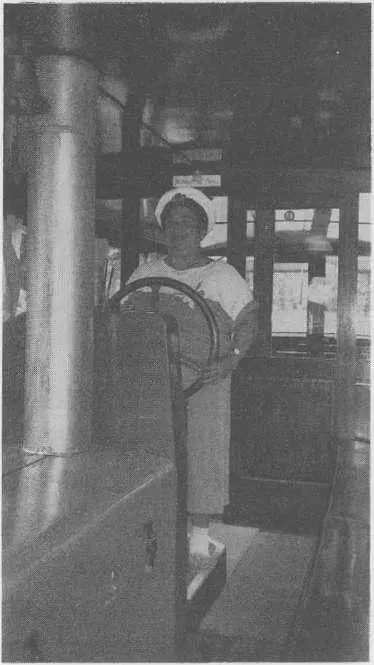

my enquiries, though they had produced much on the general history of Kissingen's Jewry, had brought very little to light concerning the Lanzberg family. But I must still say something about the trip I took up to the salt-frames in a motor launch that was moored at the edge of the spa grounds. It was about one o'clock on the day before I left, at an hour when the spa visitors were eating their diet-controlled lunches, or indulging in unsupervised gluttony in gloomy restaurants, that I went down to the riverbank and boarded the launch. The woman who piloted the launch had been waiting in vain, till that moment, for even a single passenger. This lady, who generously allowed me to take her picture, was from Turkey, and had already been working for the Kissingen river authority for a number of years. In addition to the captain's cap that sat jauntily on her head, she was wearing a blue and white jersey dress which was reminiscent (at least from a distance) of a sailor's uniform, by way of a further concession to her office. It soon turned out that the mistress of the launch was not only expert at manoeuvring her craft on the narrow river but also had views on the way of the world that were worth considering. As we headed up the Saale she gave me a few highly impressive samples of her critical philosophy, in her somewhat Turkish but nonetheless very flexible German, all of which culminated in her oft-repeated point that there was no end to stupidity, and nothing as dangerous. And people in Germany, she said, were just as stupid as the Turks, perhaps even stupider. She was visibly pleased to find a sympathetic ear for her views, which she shouted above the pounding of the diesel engine and underlined with an imaginative repertoire of gestures and facial expressions; she rarely had the opportunity to talk to a passenger, she said, let alone one with a bit of sense. The boat ride lasted some twenty minutes. When it was over, we parted with a shake of hands and, I believe, a certain mutual respect. The salt-frames, which I had only seen in an old photograph before, were a short distance upriver, a little way off in the fields. Even at first glance, the timber building was an overwhelming construction, about two hundred metres long and surely twenty metres high, and yet, as I learnt from information displayed in a glass-fronted case, it was merely part of a complex that had once been far more extensive. There was currently no access — notices by the steps explained that the previous year's hurricane had made structural examinations necessary — but, since there was no one around who might have denied me permission, I climbed up to the gallery that ran along the entire complex at a height of about five metres.

Читать дальше