And then a little later, almost before he jumped, Willie thought, “But that is romantic and wrong. It takes much more to be a man. Bhoj Narayan was choosing a short cut.”

The express slowed down, to about ten miles an hour. Willie jumped onto the steep embankment and allowed himself to roll down.

The daylight was going. But Willie knew where he was. He had a walk of three miles or so to a village and a hut, more a farmhouse, whose owner he knew very well. The monsoon was over, but now, as if out of spite, it began to rain. Those three miles took a long time. Still, it could have been worse. If courage had not come to him, and he hadn’t jumped off the train at that dangerous steep bend, he would have been taken many extra miles to where the express stopped: a day’s journey on foot, at least.

It was just before eight when he came to the village. There were no lights. People went to sleep early here; nights were long. The village street ran along the mud-and-wattle front wall of Shivdas’s high farmhouse. Willie shook the low door and called. Presently Shivdas called back, and soon, wearing almost nothing, a very dark and tall and gaunt man, he opened the low door and let Willie into the kitchen, which was at the front of the house, behind the mud-and-wattle street wall. The thatch was black and grainy from years of cooking smoke.

Shivdas said, “I wasn’t expecting you.”

Willie said, “There’s been an emergency. Bhoj Narayan has been arrested.”

Shivdas took the news calmly. He said, “Come, dry yourself. Some tea? Some rice?”

He called to someone in the next room, and there was movement there. Willie knew what that movement meant: Shivdas was asking his wife to give up their bed to the visitor. It was what Shivdas did on such occasions. The courtesy came instinctively to him. He and his wife then left the thatched main house and moved to the low, open, tile-covered rooms at the side of the courtyard at the back, where their children slept.

Less than an hour later, lying in Shivdas’s bed below the high, black, cool thatch, in a warm smell of old clothes and tobacco which was like the smell of the third-class railway compartment of just a couple of hours before, Willie thought, “We think, or they think, that Shivdas does what he does because he is a peasant revolutionary, someone created by the movement, someone new and very precious. But Shivdas does what he does because he is instinctively following old ideas, old ways, old courtesies. One day he will not give up his bed to me. He will not think he needs to. That will be the end of the old world and the end of the revolution.”

FIVE. DEEPER IN THE FOREST

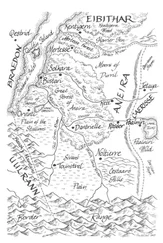

HE GOT TO his base — it had been his and Bhoj Narayan’s, his commander — late the next afternoon. It was a half-tribal or quarter-tribal village deep in the forest and so far not touched by police action; it was a place where he might truly rest, if such rest was possible for him now.

He arrived at what some people still called the hour of cow-dust, the hour when in the old days a cattle boy (hired for a few cents a day by the village) drove the village cattle home in a cloud of dust, and the golden light of early evening turned that sacred dust to soft, billowing gold. There were no cattle boys now; there were no landowners to hire them. The revolutionaries had put an end to that kind of feudal village life, though there were still people who needed to have their cattle looked after, and there were still little boys who pined to be hired for the long, idle day. But the golden light at this time of day was still considered special. It lit up the open forest all around, and for a few minutes made the white mud walls and the thatch of the village huts and the small scattered fields of mustard and peppers look well cared for and beautiful: like a village of an old fairy tale, restful and attractive to come upon, but then full of menace, with dwarves and giants and tall wild forest growth and men with axes and children being fattened in cages.

This village was for the time being under the control of the movement. It was one of a number of headquarters villages and was subject to something like a military occupation by the guerrillas. They were noticeable in their thin olive uniforms and peaked caps with a red star: trousers-people, as the tribals respectfully called them, and with guns.

Willie had a room in a commandeered long hut. He had a traditional four-poster string bed, and he had learned like a villager to store small objects between the rafters (of trimmed tree branches) and the low thatch. The floor, of beaten earth, was bound and made smooth with a mixture of mud and cow-dung. He had got used to it. The hut for some months had become a kind of home. It was where he returned after his expeditions; and it was an important addition to the list he carried in his head of places he had slept in, and was able to count (as was his habit) when he felt he needed to get hold of the thread of his life. But now the hut had also become a place where, without Bhoj Narayan, he was horribly alone. He was glad to have got there, but then, almost immediately, he had become restless.

The rule of privacy, of not saying too much about oneself and not inquiring into people’s circumstances in the world outside, which had been laid down during his first night in the camp in the teak forest, that rule still held.

He knew only about the man in the room next to his. This man was dark and fierce and with big eyes. When he was a child or in his teens he had been badly beaten up by the thugs of some big landlord, and ever since then he had been in revolutionary movements in the villages. The first of those movements, historically the most important, had faded away; the second had been crushed; and now, after some years of hiding, he was on his third. He was in his mid or late forties, and no other style of life was possible for him. He liked tramping through villages in his uniform, browbeating villagers, and talking of revolution; he liked living off the land, and this to some extent meant living off village people; he liked being important. He was completely uneducated, and he was a killer. He sang dreadful revolutionary songs whenever he could; they contained the sum of his political and historical wisdom.

He told Willie one day, “Some people have been in the movement for thirty years. Sometimes on a march you may meet one, though they are hard to find. They are skilled at hiding. But sometimes they like to come out and talk to people like us and boast.”

Willie thought, “Like you.”

And repeatedly during the evening of his return, hearing the man next door singing his revolutionary songs again and again (the way some boys at Willie’s mission school used to sing hymns), Willie thought, “Perhaps some feeling of purpose will come back to me.”

Once or twice during the night he got up and went outside. There were no outhouses; people just used the forest. There were no lights in the village. There was no moon. He was aware of the sentries with guns. He gave the password, and then a little while later he had to give it again, so that as he walked he felt the strange word “comrade” echoing about him, as question and reassurance. The forest was black, and full of sound: sudden wing-beating, amid cries of alarm and pain from birds and other creatures, calling for help that wouldn’t come.

Willie thought, “The most comforting thing about life is the certainty of death. There is no way now for me to pick my way back to the upper air. Where was the upper air? Berlin? Africa? Perhaps there is no upper air. Perhaps that idea has always been a mirage.”

In the morning someone knocked on the door of Willie’s room and came in before Willie answered. The man who came in carried an AK-47. He was as pale as Einstein, but much smaller, about five feet. He was very thin, with a skeletal but handsome face and bony, nervous hands. Another six or seven inches would have given him an immense presence.

Читать дальше