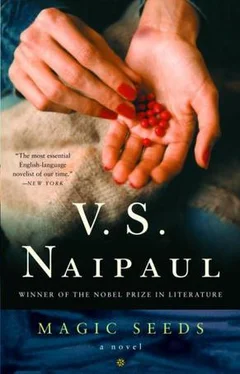

INTERNATIONAL ACCLAIM FOR V. S. NAIPAUL AND

Magic Seeds

“Naipaul has a great gift for … crushingly economical observations…. [His] books … are passionately engaged with the world.”

— The New York Review of Books

“An elegant little story — with a moral…. What is distinctive [is] the light that it sheds on India, especially rural India.”

— The Wall Street Journal

“A masterful and evocative writer…. The language is clear and readable…. [His] ideas are rich, provocative, and worthy.”

— Rocky Mountain News

“Original, ruthlessly honest, intellectually stimulating and masterfully written.”

— The Times (London)

“There is a terrible purity to the prose. It is clean and dry, tough but never brittle…. [Magic Seeds] revisit[s] most, if not all, of the themes, obsessions and social worlds of his earlier fiction.”

— Newsday

“Offers a gripping glimpse at the sadness of a dream deferred.”

— Entertainment Weekly

“Bleakly comic…. Full of all Naipaul’s exact and cumulative brilliance.”

— The Guardian

“A remarkably astute … witness to the world with an extraordinary contribution to literature.”

— The Village Voice

“Riveting…. Masterful prose … indelible images.”

— Commentary

“[Naipaul] has achieved the top of his form.”

— The Star-Ledger (Newark)

“Magic Seeds occupies an identifiable place in Naipaul’s philosophy, and those who generally enjoy his work will like what’s here. Readers unfamiliar with his work have much to gain as well…. His precise art offers something revelatory.”

— The Plain Dealer

“Richly drawn…. Vivid and revealing.”

— The Decatur Daily

“Beautiful, enchanting prose…. In some ways, Willie [Chandran] embodies every character Naipaul has created in his brilliant career.”

— Associated Press

LATER — IN THE teak forest, in the first camp, when during his first night on sentry duty he had found himself for periods wishing only to cry, and when with the relief of dawn there had also come the amazing cry of a far-off peacock, the cry a peacock makes in the early morning after it has had its first drink of water at some forest pool: a raucous, tearing cry that should have spoken of a world refreshed and remade but seemed after the long bad night to speak only of everything lost, man, bird, forest, world; and then, when that camp was a romantic memory, during the numbing guerrilla years, going on and on, in forest, village, small town, when to travel about in disguise had often appeared to be an end in itself and it was possible for much of the day to forget what the purpose of the disguise was, when he had felt himself decaying intellectually, felt bits of his personality breaking off; and then in the jail, with its blessed order, its fixed timetable, its protecting rules, the renewal it offered — later it was possible to work out the stages by which he had moved from what he would have considered the real world to all the subsequent areas of unreality: moving as it were from one sealed chamber of the spirit to another .

IT HAD BEGUN many years before, in Berlin. Another world. He was living there in a temporary, half-and-half way with his sister Sarojini. After Africa it had been a great refreshment, this new kind of protected life, being almost a tourist, without demands and without anxiety. It had to end, of course; and it began to end the day Sarojini said to him, “You’ve been here for six months. I may not be able to get your visa renewed again. You know what that means. You may not be able to stay here. That’s the way the world is made. You can’t object to it. You’ve got to start thinking of moving on. Do you have any idea of where you can go? Is there anything you feel you want to do?”

Willie said, “I know about the visa. I’ve been thinking about it.”

Sarojini said, “I know your kind of thinking. It means putting something to the back of your mind.”

Willie said, “I don’t see what I can do. I don’t know where I can go.”

“You’ve never felt there was anything for you to do. You’ve never understood that men have to make the world for themselves.”

“You’re right.”

“Don’t talk to me like that. That’s the way the oppressor class thinks. They’ve just got to sit tight, and the world will continue to be all right for them.”

Willie said, “It doesn’t help me when you twist things. You know very well what I mean. I feel a bad hand was dealt me. What could I have done in India? What could I have done in England in 1957 or 1958? Or in Africa?”

“Eighteen years in Africa. Your poor wife. She thought she was getting a man. She should have talked to me.”

Willie said, “I was always someone on the outside. I still am. What can I do here in Berlin?”

“You were on the outside because you wanted to be. You’ve always preferred to hide. It’s the colonial psychosis, the caste psychosis. You inherited it from your father. You were in Africa for eighteen years. There was a great guerrilla war there. Didn’t you know?”

“It was always far away. It was a secret war, until the very end.”

“It was a glorious war. At least in the beginning. When you think about it, it can bring tears to the eyes. A poor and helpless people, slaves in their own land, starting from scratch in every way. What did you do? Did you seek them out? Did you join them? Did you help them? That was a big enough cause to anyone looking for a cause. But no. You stayed in your estate house with your lovely little half-white wife and pulled the pillow over your ears and hoped that no bad black freedom fighter was going to come in the night with a gun and heavy boots and frighten you.”

“It wasn’t like that, Sarojini. In my heart of hearts I was always on the Africans’ side, but I didn’t have a war to go to.”

“If everybody had said that, there would never have been any revolution anywhere. We all have wars to go to.”

They were in a café in the Knesebeckstrasse. In the winter it had been warm and steamy and civilized with its student waiters and waitresses and welcoming to Willie. Now in late summer it was stale and oppressive, its rituals too well known, a reminder to Willie — in spite of what Sarojini said — of time passing fruitlessly by, calling up the mysterious sonnet they had had to learn by heart in the mission school. And yet this time removed was summer’s time …

A young Tamil man came in selling long-stemmed red roses. Sarojini made a small gesture with her hand and began to look in her bag. The Tamil came and held the roses to them, but his eyes made no contact with theirs. He claimed no kinship with them. He was self-possessed, the rose-seller, full of the idea of his own worth. Willie, not looking at the man’s face, concentrating on his brown trousers (made by tailors far away) and the too-big gold-plated watch and wristlet (perhaps not really gold) on his hairy wrist, saw that in his own setting the rose-seller would have been someone of no account, someone unseeable. Here, in a setting which perhaps he understood as little as Willie did, a setting which perhaps he had not yet learned to see, he was like a man taken out of himself. He had become someone else.

Willie had met a man like that one day, some weeks before, when he had gone out on his own. He had stopped outside a South Indian restaurant, without customers, with a few flies crawling on the plate-glass windows above the potted plants and the display plates of rice and dosas, and with small amateurish-looking waiters (perhaps not really waiters, perhaps something else, perhaps electricians or accountants illegally arrived) lurking in the interior gloom against the cheap glitter of somebody’s idea of oriental decoration. An Indian or Tamil man had come up to Willie then. Soft-bodied, but not fat, with a broad soft face, and with a flat grey cap marked with thin blue lines in a wide check pattern, like the “Kangol” golfer’s caps that Willie remembered seeing advertised on the back pages of the early Penguin books: perhaps the style had come to the man from those old advertisements.

Читать дальше