I put the ring binder back in its place on the shelf, and got ready to leave the library, feeling embarrassed and conned, when, as I passed the computer, the clerk asked me if I'd found what I was looking for. I confessed that I hadn't.

'Oh, but don't give up so quickly.' He stood up and, not giving me time to explain anything, went to the shelf and got the binder down again. 'What's the person's name?'

'Pere or Pedro Figueras Bahi. But don't worry: he probably wasn't ever in any prison.'

'Then he won't be here,' he said, but insisted: 'Have you an idea of when he might have been in prison?'

'In '39,' I yielded. 'At the latest '40 or '41.'

The clerk quickly found the page.

'No one of that name,' he confirmed. 'But the prison officer could have made an error in writing it down.' He smoothed his moustache and muttered: 'Let's see. .'

He flipped ahead and back through the pages of the register several times, running down the lists of names with his index finger, which finally stopped.

'Piqueras Bahi, Pedro,' he read. 'That must be him. Wait a moment, please.'

He went out through a side door and returned a short while later, smiling and carrying a document case with faded covers.

'There's your man,' he said.

The document case did in fact contain Pere Figueras' dossier. Extremely excited, my self-esteem suddenly restored, and telling myself that if Pere Figueras' prison stay wasn't an invention then nor was the rest of the story, I examined the dossier. It stated that Pere Figueras was a native of Sant Andreu del Terri, a municipality assimilated over time into Cornellá de Terri. That he was a farmer and single. That he was twenty-five years old. That his background was unknown. That he'd been incarcerated in the prison of the Military Government, without any charge being laid against him, on 27 April 1939, and that he'd left it not even two months later on 19 June. It also stated that he'd been released by the General Auditor in accordance with an order included in the dossier of a certain Vicente Vila Rubirola. I looked up Rubirola in the index, found him, and asked the clerk for his dossier, which he brought me. A member of the Catalan Republican Left, Rubirola had been in prison after the revolution of 1934 and had been sent back there at the end of the war, the very same day as Pere Figueras and his eight comrades from Cornellá de Terri; all of them were freed on 19 June, the same day as Figueras, in accordance with an order from the Auditor General, which didn't specify any reason justifying this decision; Vila Rubirola, however, had been sent back to jail in June of the same year and having been tried and found guilty, hadn't finally left it again for another twenty years.

I thanked the archive clerk and, as soon as I got to the newspaper office I phoned Aguirre. Many of the names of those imprisoned with Figueras were familiar to him — the majority notorious activists of left-wing parties — and especially Vila Rubirola, who in the early days of the war had participated in the assassination, in Barcelona, of the Secretary-General of the Municipality of Cornellá de Terri. According to Aguirre, the fact that Pere Figueras and his eight comrades were incarcerated without explanation was perfectly normal at the time, when everyone who'd had any kind of military or political link to the Republic had their past submitted to rigorous albeit arbitrary scrutiny, and meanwhile they stayed in prison; nor did he find it strange that Pere Figueras was released after a short time, as this happened often with those the new regime didn't consider a danger.

'What does strike me as odd is that someone as well known as Vila Rubirola, and a few of the others who went into prison with Figueras, should have been released with him,' observed Aguirre. 'And what I really just can't understand is all of them getting out the same day without any explanation, and all so that Vila Rubirola — and I wouldn't be surprised if one or two others — were sent straight back in. I don't get it.' Aguirre fell silent. 'Unless. .'

'Unless what?'

'Unless someone interceded,' Aguirre concluded, avoiding the name we both had in mind. 'Someone with real power. A hierarch.'

That very evening, having dinner with Conchi in a Greek restaurant, I solemnly announced, because I felt the need to announce it solemnly, that after ten years of not writing a book, the moment had come to try again.

'Bloody brilliant!' shouted Conchi, who was hoping to add a third book to the two escorting her Virgin of Guadalupe in the living room; with a piece of pita bread dipped in tzatziki on its way to her mouth, she added: 'I hope it's not a novel.'

'No,' I said, very confidently. 'It's a true tale.'

'What's that?'

I explained; I think she understood.

'It'll be like a novel,' I summed up. 'Except, instead of being all lies, it's all true.'

'I'm glad it's not going to be a novel.'

'Why's that?'

'No reason,' she answered. 'It's just that — well, honey, I don't think imagination is really your strong suit.'

'You're a real sweetheart, Conchi.'

'Don't take it like that, darling. What I meant to say was. .' Since she didn't know how to say what she meant to say, she picked up another piece of pita bread and said, 'Anyhow, what's the book about?'

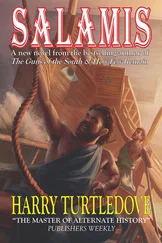

'The battle of Salamis.'

'The what?' she screeched.

Several pairs of eyes turned to look at us, for the second time. I knew the story line of my book wasn't going to appeal to Conchi, but, since I didn't want her to kick up a fuss and call everyone's attention to us, I tried to explain it briefly.

'What are you like?' was her comment, accompanied by a look of disgust. 'How can you want to write about a fascist with the number of really good lefty writers there must be around! Garcia Lorca, for example. He was a red, wasn't he? Ooh,' she said not waiting for a reply, reaching under the table: alarmed, I lifted the table cloth up a bit and looked, 'God, my pussy's so itchy.'

'Conchi!' I scolded her in whisper, sitting up quickly and forcing a smile while glancing around at the neighbouring tables, 'I'd appreciate it, when you go out with me, if you'd at least wear panties.'

'What an old fart you are!' she said with her most affectionate smile, but without bringing the submerged hand out into the open; I felt her toes creeping up my calf. 'Don't you think it's sexy? Anyway, when do we start?'

'I've told you a million times I don't like doing it in public toilets.'

'I didn't mean that, dummy. I mean when do we start on the book?'

'Oh that,' I said as one flush went up my leg and another down my face. 'Soon,' I stammered. 'Very soon. As soon as I finish the research.'

But it would actually take me a while yet to reconstruct the story I wanted to tell and to get to know, if not each and every one of its hidden aspects, at least what I judged its essential ones. In fact, for many months I spent all my free time at the newspaper studying the life and work of Sánchez Mazas. I reread his books, I read a lot of the articles he published in the press, many articles by his friends and enemies, his contemporaries, and also everything I came across about the Falange, fascism, the Civil War, and the equivocal, changeable nature of the Franco regime. I scoured libraries, newspaper archives, public records. I travelled to Madrid several times, and constantly to Barcelona, to talk to scholars, professors, friends and acquaintances (or friends of friends and acquaintances of acquaintances) of Sánchez Mazas. I spent an entire morning at the Sanctuary of Collell, which, as I was told by Mossen Juan Prats — the priest with the shiny bald patch and devout smile who showed me the garden with its cypress and palm trees and immense empty halls, low corridors, stairways with wooden handrails and deserted classrooms where Sánchez Mazas and his cellmates had wandered like premonitions of shades — had, once the war was over, gone back to being used as a boarding school for boys until, a year and a half before my visit, it was reduced to its present lonely status of a conference centre for pious associations and occasional lodging for sightseers. It was Father Prats himself, only just born when the events in question occurred in Collell, but not unaware of them, who told me the real or apocryphal story according to which, when Franco's regulars took the Sanctuary, they left not a single prison guard alive. Father Prats also gave me precise directions to get to the spot where the execution took place. Following them, I left the monastery by the access road, arrived at a stone cross commemorating the massacre, turned left down a path which snaked through pines and came out in the clearing. I stayed there for a while, walking beneath the cold sun and immaculate, windy October sky, not doing anything other than sounding out the leafy silence of the forest and trying in vain to imagine the light of another less crystal clear morning, that inconceivable January morning, sixty years ago in the same place, when fifty men suddenly faced death and two of them managed to evade its grasp. As if a revelation by osmosis might await me, I stayed there a while. . I didn't feel anything. So I left. I went to Cornellá de Terri, because the same day I was having lunch with Jaume Figueras, who that afternoon took me to see Can Borrell, the Ferré's old house, Can Pigem, the Figueras' old house, and the Mas de la Casa Nova, which had been Sánchez Mazas', Angelats' and the Figueras brothers' temporary hiding place. Can Borrell was a farm located in the township of Palol de Rebardit; Can Pigem was in Cornellá de Terri; the Mas de la Casa Nova was between the two villages and in the middle of the woods. Can Borrell was uninhabited, but not in ruins, so was Can Pigem; the Mas de la Casa Nova was uninhabited and in ruins. Sixty years before they'd surely been three quite different houses, but time had virtually equalled them, and their common air of abandonment, of stone skeletons among whose fleshless ribcages the winds groaned in the autumn evening, held not a single suggestion that anyone had ever once lived in them.

Читать дальше