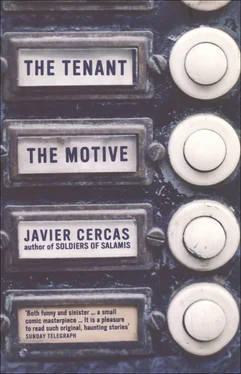

Javier Cercas

The Tenant and The Motive

‘Have you never been in love?’

‘Yes. With you.’

‘And how do you love me?’

‘With this.’

‘That’s your liver.’

‘Sorry, that’s not what I meant. I love you with my heart.’

SILVERIO LANZA

Mario Rota went out for a run at eight o’clock on Sunday morning. He immediately noticed the street was suffused in a halo of mist: the houses opposite, the cars parked by the sidewalk and the globes of light from the street lamps seemed to shimmer with an unstable and hazy existence. He did a few arm and leg stretches on the tiny rectangle of lawn in front of the house and thought: Fall’s here already. Instinctively, while jumping up and down and pulling his knees up to his chest, he reconsidered. He told himself September had barely begun, and vague threats flitted through his mind of ecological catastrophes. The initial symptoms, according to a well-known Italian weekly he’d been reading on the plane, on the way back from his summer vacation, would be a gradual disruption to each season’s normal weather conditions. After this worrying reflection he smiled somewhat incongruously. He went back inside and came out again a moment later, this time with his glasses on. The mist having dissolved, Mario began to run along the path of greyish flagstones between the road and the meticulous gardens, enclosed by flowerbeds and wooden fences lined up in front of the houses.

Although the difficult relationship he maintained with reality withheld any benefits that might have resulted, Mario was a fanatic for order: when he went out for a run each morning he followed an identical itinerary. Last year he ran up West Oregon, crossing Coler, McCollough and Birch, turned left on Race and kept going till Lincoln Square, an early twentieth-century plaza dominated by the mass of new stone and strange capitals of the First United Methodist Church. There he took Springfield, now on the way back, past automotive repair shops, banks, supermarkets and pizzerias, and when he got to Busey, turned left again and carried on until arriving back at West Oregon. This year, however, he’d decided to modify his route. Since he’d resumed his morning jogging routine, having returned from his vacation two days earlier, he ran in the opposite direction: now he turned left on McCollough, where the First Church of Christ Scientist stood at the corner of West Oregon, and headed towards the west of the city, crossing Nevada, Washington and Orchard. Then he ran along Pennsylvania to the end, where it was cut off by Lafayette Avenue; beyond that he ran across a grass field and up a gentle slope topped with a bare spot. Mario stopped for a moment at the crest, inhaled and exhaled deliberately, trying to keep his breathing regular, briefly admired the scenery and then took the same route back: colonial two-storey wooden houses painted white, red or olive-green, with ironwork screen-doors and garden fences covered with creepers; brick bungalows with sloping roofs; big mansions converted into student residences; squirrels swarming walnut, plane and chestnut trees, their profuse branches occasionally obstructing the paths of greyish flagstones running between the road and the meticulous gardens.

It was eight o’clock on Sunday morning. The streets were deserted. The only person he saw during the first five minutes of his run was a young woman crouched down beside an anemone bush in the back garden of the First Church of Christ Scientist, as he was turning right on to McCollough. The girl turned: she bared her teeth in a devout smile. Mario felt obliged to return the greeting: he smiled. Later, by then on Pennsylvania, he crossed paths with a grey-haired man in shorts and a black T-shirt, who was jogging in the opposite direction. The man’s expression seemed concentrated on a buzzing emitted from two earphones fed from a cassette player strapped to his waist. After that came a postal truck, an old, bandy-legged black man, who supported his decrepit steps with a wooden walking stick, a young woman with diligent Oriental features, a family having a boisterous breakfast on the front porch, complete with laughter and parental warnings. When, on the way home, he turned back on to West Oregon, the city seemed to have resumed its daily pulse.

That’s when he twisted his ankle.

Since he was feeling agile and keeping his breathing even, he picked up the pace for the last part of his run. When he got to West Oregon he tried to take a little short cut by jumping over a bed of dahlias. He landed badly: his left instep took the weight of his whole body. At first he felt a piercing pain and thought he’d broken his foot. With some difficulty, sitting on the lawn, he took off his running shoe and sock, checked that his ankle wasn’t swollen. The pain soon eased and Mario told himself that with any luck the mishap wouldn’t matter at all. He put his sock and shoe back on, stood up and began to walk carefully. A sharp pain tore through his ankle.

He arrived home with an obvious limp. On the porch, accompanied by a man, was Mrs Workman.

‘Mr Rota, what happened?’ said the woman with alarm, pointing at Mario’s ankle. ‘You’re limping.’

Mrs Workman was a tiny old woman, a widow with white curly hair, scrawny hands and lively green eyes. She was also Mario’s landlady.

‘Nothing serious,’ said Mario, grabbing on to the railing to pull himself up the porch steps. Neither Mrs Workman nor the man came to help him. ‘I just twisted my ankle in the most idiotic way.’

‘I hope it’s not serious,’ said Mrs Workman.

‘It won’t be,’ said Mario, as he reached the top of the steps.

Mrs Workman changed her tone.

‘I’m so pleased to have bumped into you, Mr Rota,’ she said, stretching out a hand: Mario felt as if he was shaking a bundle of dry skin and bones. ‘Let me introduce Mr Berkowickz. Barring unforeseen circumstances he’ll be the new tenant of the apartment across from yours, where Nancy used to live.’

‘Nancy’s moved?’ asked Mario.

‘She was offered a job in Springfield,’ said Mrs Workman. ‘A good job. I’m happy for her, she’s a nice girl; I loved her like a daughter. I suppose you’ll also be pleased that Nancy’s moved to Springfield,’ she added ambiguously.

‘Of course,’ Mario agreed hurriedly.

‘As for her apartment,’ Mrs Workman went on, looking at the new tenant with eyes that sought confirmation of her words, ‘I got the impression Mr Berkowickz was pleased with it.’

‘Absolutely,’ Berkowickz said. ‘It’s exactly what I need.’

He paused, then looked at Mario. ‘Besides,’ he added, ‘I’m sure I’ve found the perfect neighbour.’

Berkowickz cited the title of the only specialist article Mario had published in the last three years, in Italica. Smiling and turning to Mrs Workman, he declared that he and Mario were colleagues, researching matters of a similar nature, and that they’d undoubtedly be working in the same university department. Mrs Workman could not hide the satisfaction this happy coincidence gave her: a surprised smile lit up her face. Only then did Mario take a good look at Berkowickz. He was a tall, broad-shouldered man with suntanned skin and a frank expression in his eyes; his incipient baldness didn’t contradict the youthful air his face exuded. He was dressed with elegance but without affectation. Otherwise, his appearance was less that of a university professor than of an elite athlete. But perhaps his most striking feature was his solid self-confidence revealed by each and every one of his gestures, as if he’d planned them in advance, or as if they were ruled by necessity.

Читать дальше