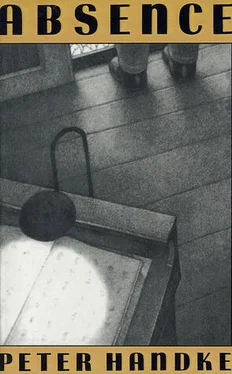

Peter Handke - Absence

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Handke - Absence» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2000, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Absence

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2000

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Absence: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Absence»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

follows four nameless people — the old man, the woman, the soldier, and the gambler — as they journey to a desolate wasteland beyond the limits of an unnamed city.

Absence — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Absence», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Though we were alone in the room, the festive illumination, the trailing plants along the walls, and the bay trees that flanked the tables gave us the feeling that we were surrounded by invisible people. Every time the waiter came through the swinging door with his brass, dome-shaped cart — revealing a kitchen so glaringly white as to efface any figures that may have been there-he was followed by cries and a hubbub of busy voices, as though this were a moment of feverish activity. We were sure that when the meal was over the old man would appear in the doorway in a chef’s hat and receive our applause, smiling bashfully, with the modesty characteristic of master chefs.

Suddenly the hall was full of diners; additional waiters hurried in from all directions; evidently people kept late dinner hours in this town; and though we had seen only foreigners in the streets, all these late diners seemed as casual as only natives can be.

Each time we looked up in vain, our hope waned a little; each time we mistook someone for the Awaited One, our memory of the man himself grew dimmer. Did he really exist? Weren’t he, his pencil, and his notebook mere delusions? And who were we — the woman with the pursed lips, the young fellow with the dirty fingernails, the unknown man with the pimp’s bracelet and the corresponding bundle of banknotes?

When did the thought come to us, all of us at once, that the missing man had vanished forever? It happened suddenly in the dining room that was once again empty — the waiters had left long ago; the festive illumination and harpsichord music were unchanged, but the singing voice was gone. A thought without an image, accompanied by a nausea that made us speechless, incapable of so much as an outcry. Each for himself, without a parting word, by separate itineraries — elevator, stairs, service entrance — we went to our separate rooms, followed by the music, which resounded through the corridors, that music of which the poet said that heard in the distance it filled all those with horror who knew that they would never return home.

All night long the city seemed to be one vast railroad station: in all the rooms shunting sounds were heard, interspersed with loudspeaker voices calling out strings of place-names such as “Venice-Milan-Ventimiglia-Lyon-Paris,” or “Istanbul-Salonika-Belgrade-Zagreb-Munich-Ostend,” and it seemed to us that these resonant litanies intensified the effect of the music. The only other sounds were strangely tinny bells and an occasional whimpering and howling nearby, so wild that one of us thought of a madhouse, one of a prison, and one of a zoo. But never a barking, not even in the distance, as though, perhaps since the earthquake, there was not a single dog in the whole city.

But to make up for it, the cocks started crowing in the early darkness, so many in so many different places that we thought we were out of doors and that hotel and city were an illusion. Our only certainty was that something had happened to the old man, and that certainty, instead of calming us, made us see ghosts. Didn’t people who had just died — especially those who had been dear to one in life — become terrifying revenants if one hadn’t taken leave of them properly?

So then the old man went into the phase of evil absence. And it persisted. He lurked in the darkest corners of the room and attacked us in our instant-long insomniac dreams; and in the morning sun he was still there, ready to pounce. At the very same moment, one of us screamed because he had seen the old man’s cape on a clothes hanger, one recoiled from the glove on the balcony railing, while one pulled his knife and spun around because he had mistaken his own hair, hanging down over his face, for a marauder. The “dead man” had become a multitude of dead men, and all had banded together against us forlorn survivors.

Breakfast was served us on the terrace overlooking the hotel park. Though seated at the same table, we were not in any sense “together.” We were strangers to one another, more so than the night before. Shoulder to shoulder, we seemed to have partitions between us. Had we ever had anything in common? Stupid mishap, falling in with these particular people! Stupid illusion of kinship that has sent me and these people to this weird place.

Worse than estrangement, there was hostility between us. None of us found the strength to go his separate way or to content himself with staying there, looking around him and playing with his thoughts. Glued to the spot, unable to take an interest in anything, we were enemies and would soon come to blows. The woman kept crumpling slips of paper and setting fire to them, as though burning us in effigy. The gambler shivered in the balmy air and at intervals exploded in suicidal laughter, as though about to run amok. Even the mild-mannered soldier, staring at always the same line in his book, incapable of reading, red in the face, bared his teeth from time to time. Losing each other’s contours, we were no longer face to face; we did what we had never done before — we judged, deprecated, and in the end hated one another.

It was a clear, cloudless day in the early fall, with a breeze such as one might imagine on an atoll in the South Seas. The whole plateau unfolded before us; in our normal state of mind every rise and fall in our journey would have come alive for us; with a sense of being young that we would never have had without our journey, we would have seen ourselves as human clouds, advancing from station to station, resting, sleeping, indestructible. We would have delighted in the glittering streak of mist at the foot of the pedestal — or was it a field with a sheet of plastic over it? No, it was actually the sea. The one giant cedar tree in the garden, deep-dark, bushy, covered with candle-shaped cones, was the façade of a grave-countenanced cathedral which, had it been offered us at eye level without our having to look up, would have impressed us as the natural goal of our journey.

But here where we had arrived we felt we had gone astray. The light was too much for us and its beauties were not only meaningless but offensive. The pillar-framed view from our arbor seemed a mockery. The vines blowing from shadow to sunlight wounded the soul. Never would we have dreamed that the birds of heaven-except, perhaps, for crows — could have become repugnant to us; but now we heard the same mocking screams from each of the many varieties in the cedar bower, and when the wood pigeons fluttered in place as though about to land on empty air, their slender throats had swollen to bull necks.

There was also our sense of guilt. Everywhere people were doing something, working or studying — here in the park, for instance, the gardeners with their apprentices; and down in the city those masons who had been working for years, faithfully rebuilding the cathedral with the original stones. What better occupation could there be in this day and age? And weren’t those men, without being in a hurry, more than usually absorbed in their work? The lamb on the façade was already looking over its shoulder into space. The relief of the dove faced the morning sun with falcon’s eyes. The three stone kings in their niches, all deep in blissful sleep, were once again following the star in their dream. Only the tip of the steeple still lay where it had been hurled, far away, in the midst of a thicket that had grown up around it. To us idle onlookers on the terrace, who had only to turn our heads to be served like kings, the repeated piping of the cash register in the background sounded like the distress signal of a rudderless space capsule that was carrying us away from our earth. So this was what came of trying to get rid of history, individual as well as universal, and escaping into so-called geography?

We were terribly at odds, and there was nothing to pull us together again. If the old man had reappeared and made a proposal to all of us, we would have laughed, not only at his proposal, but at his person as well.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Absence»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Absence» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Absence» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.