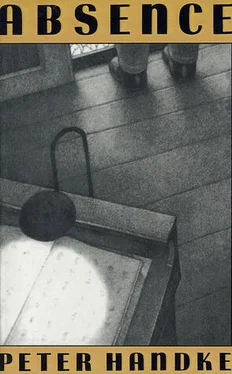

Peter Handke - Absence

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Handke - Absence» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2000, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Absence

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2000

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Absence: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Absence»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

follows four nameless people — the old man, the woman, the soldier, and the gambler — as they journey to a desolate wasteland beyond the limits of an unnamed city.

Absence — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Absence», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This last word had been shouted. Knife in hand, the soldier jumped up from the bench. But instead of throwing the knife, he threw pebbles, which rained down on the rock. Outside, the upland stars flickered as though twisted by the wind. A wild boar was a motionless hump in the underbrush; some smaller humps lay beside it. A cornfield with its glittering, waving leaves counterfeited the moving surface of a lake; the handcart alongside it played the part of a boat. The curving glow over the undulating, always identically distant horizon rose from the big seaport at the foot of the plateau; it was as though the soldier’s shout had landed there and the glow was its echo.

Much later, as we were all lying on our bed of foliage, the woman spoke. The oil lamp had been turned low, and the room lay in half darkness. As we were lying prone, our heads to one side and our hands over our eyes, it was impossible to tell who was awake and who was asleep. Only the woman was visible, lying with her eyes closed and her face framed and half buried in her pillow of foliage, as children sometimes do in their autumn games. And so clear was her toneless voice that, again as with children, it would have been hard to say whether she was talking in her sleep or pretending. On her couch, which was somewhat higher than the others, she lay as on a royal bed, and with her under it the army blanket lost its military look. This is what she said: “You’re a liar. You’ve deceived me from the first. You’ve never meant what you said. You’re a cheat, a con man, a swindler. You lured me into a trap. If I go to the dogs, you’re to blame and you should be punished for it. DIM is not an unconquered sun god, it’s a brand of pantyhose. You’re a rotten reader. You say: I like to be disturbed; the truth is, you can only be alone, and not just with yourself, no, you’ve got to be alone with your books, your gold pencils, and your stones. Your supposed sundial wasn’t scratched on the rock centuries ago by some great man, but only yesterday by a child at play, and it’s not a sundial, it’s just a scribble. You’re a phony scholar. There’s no inspiration at the bottom of your reading, deciphering, and interpreting — they’re just a quirk; you invented the voice that said to you: Take this and read; ever since you’ve been able to see, you’ve been obsessed with your written word, your letters, your signs. Your Roman milepost was a prop left here by some filmmakers. Same with your oldest inscriptions, they came from a movie set. Tap your bronze — it sounds hollow; run your fingernail over your runes — the cardboard will squeak. Your Egyptian scarab was manufactured last year in Murano, and the flower on your fragment of a Cretan vase was etched in Hong Kong. And even if they are authentic, what they have to say is old stuff and signifies nothing today. Their meaning is lost, their relevance forgotten, their context broken off. Far from recapturing the thread, we can’t even get an inkling of it. Only your words on your false and authentic stones remain, and they have been drowned out not only by the thunder of war machines but by the fall of the very first empire. Never again will your Euphrates and your Tigris flow from Paradise. Never again will your child carried across the sea by a dolphin serve as a symbol of solace on the graves of those who die young. In none of your books will there be another Odysseus, another Queen of Sheba, another Marcellus. You yourself no longer believe in the fords you’ve shown me. Your springs mean no more to you than they do to me; your crossroads and clearings have long ceased to be special places for you; at your watersheds you stand bewildered like any other tourist — what good does it do you to know that the water from one of the twin pipes flows into the Baltic and from the other into the Black Sea? And for years your country here hasn’t been to you what it once was. The emptiness here no longer promises you anything; the silence here has ceased to tell you anything; your walking here has lost its effect; the present here, which once seemed so pure and uniquely luminous to you, darkens between your steps as it does anywhere else. Here, too, empty has become empty, dead dead, the past irrevocable, and there is nothing more to hand down. You should have stayed alone in your room. Out of the sun, curtain drawn, artificial light, easy chair, television, no more adventures or distractions, gaze straight ahead, no more looking for inscriptions out of the corner of your eye, no more glancing over your shoulder into dark recesses, no more turning about, no more prayer, no more talk; only silence, without you. It would be so lovely there now, without you, in an entirely different prairie from yours. Vanity Fair! Vogue! Amica! Harper’s Bazaar!” While she was speaking, the wind had slackened, and by the time she finished, it had died down completely. In the upper window openings the night sky had come closer; the veil hanging from a branch was the Milky Way. The four sleepers lay in different directions, as though dropped at random. The gambler’s hand above the blanket took the woman’s hand under the blanket, and so their hands rested. Suddenly the sleeping woman cried out with pain; her breath caught, then came a sob that shook her whole body, and tears streamed from her closed eyes. In her dream she saw a man who had just died, and that made her the last human being in the world. She cowered on the ground, and all she had left was a childlike whimpering, stopping and starting up again each time on a higher note, filling the room but heard by no one.

The countryside is utterly silent. The cave dwelling takes on steel edges in the dawning light. The mounds of bat droppings on the floor of the bunker are shaped like sleeping bags. No more smoke above the chimney hole; no dew in the grass; certain stones have holes in them like animal skulls, the sky enclosed in them is a grayer, more ancient stone. The old man with the canvas-covered book has stepped out into the open; wet as though newly washed, his hair shows its length. He combs it without a mirror, looking inward. Instead of his cape, he is wearing a wide shirt; hanging down over his belt and buttoned askew, it is well suited to his clown’s trousers; but the creases are sharp, as though he were wearing it for the first time.

He walks quickly, at first swinging his notebook like a discus, then tucking it into his trousers and drumming on it to the rhythm of his steps. The drumming sounds hollow and soon fills the wilderness; little by little the details of the landscape emerge from the gloom and take on contours.

Later, when, glancing over his shoulder, he sees the cave dwelling as nothing more than a rock among many others, the old man begins to sing. He has long since changed direction — what started out as an open plateau has acquired steep walls on all sides. Now he is roaming through a jungle almost all of whose trees are dead — roaming happily, as though triumphing every time he stumbles. He has kept on writing, but now he does it while walking, no longer in his book but in the air, drawing big letters. In a hoarse falsetto voice he sings:

Into the silence.

Alone into silence.

Silence alone.

Where are you, silence?

You’ve always been good to me, silence.

I’ve always been happy in you, silence.

Time and again, I’ve become a child with you, silence;

through you I came into the world, silence;

in you I learned to hear, silence;

from you I acquired a soul, silence;

by you alone have I let myself be taught, silence;

from you alone have I gone as a man among men, silence.

Be to me again what you were, silence.

Embrace me, silence.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Absence»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Absence» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Absence» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.