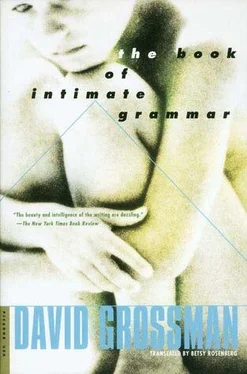

The night after, I crouched outside the hut again as usual; there were eyes in the back of my head, though, and Molochinko jumped up onme, hippety-hop, and in through the hatch, and I turned and ran in the opposite direction; I was an animal in those days, for better or worse I was an animal, that’s how I got out of the ice, Miss Edna; he was pounding with his whole body now, pressing his chest and loins against the wall, and Aron thrust the door open and fled, down four steps at a time, home through the rain, through the darkness, straight into bed with all his clothes on, with the blanket over his head, training himself in secret like a sumo. And so, Miss Bloom, Miss Edna, I ran for maybe half the night, till I couldn’t hear the dogs barking or the people shouting anymore, but all night long I saw the smoke rising out of the hut, and I never even knew the woman, only her smell.

With all his might he smashed the wall. A last chunk of stone was stuck between the bricks and he waved his hammer at it. Another bolt of lightning zigzagged across the sky, but lassitude leaked in between the raindrops, as though all the spunk had gone out of winter. Papa bellowed hoarsely and struck again. And again. Edna sprawled in her armchair, all-seeing though her eyes were shut tight, with an unfamiliar violence whirling up from the abyss inside her, causing her little frame to tremble and shake; a spark flew out of the somber sky, and a bolt of lightning spat fire, but the rain had relented. Papa groaned again and paused: the rest of the wall caved in. Lightning hissed with rancor and recoiled, and there was a moment’s silence. Then the clouds began to fade into the distance, withering as they mounted higher, like an assembly of grumbly old men.

Somewhere a window opened. The lamps in the street went on. The apartment was filled with a gentle light. Papa sank down, utterly exhausted. He raised his heavy head in search of Edna and was surprised to find her crouching under the piano, her arms crossed over her knees. Her eyes caressed him with tender compassion. And he smiled at her apologetically, as though waking from a dream, reflecting how young she looked, how fragile, not much older than his Aron.

“This wall is finished,” he said at last in a husky voice.

Edna stood up and stumbled and sank down again. She laced her fingers as tightly as she could to stop the trembling. Papa approached and stood limply before her, waiting for her to say something. When he looked he saw her bashful smile, the gleam of mischief in her eyes, and her finger pointing at the kitchen wall.

“Hinda will want more money,” he said. This was his first mention of Mama, and the way he said her name filled Edna with glee, as though the two of them had become conspirators against her.

She thought a moment. Her bank clerk, a little man who behaved like a tall one and always tried to flirt with her, had warned: profits on the fund that paid for her annual summer trip were poor this year; she shuddered at the thought, but suddenly imagined the way he moved his hips, and something inside her, a bucking bronco, whinnied and stamped before the gaping bespectacled eyes of the clerk. “A hundred and twenty,” she said in a scintillating voice.

“No, no,” said Aron’s father. “That’s too much. It isn’t a very big wall.”

“But it may be tricky. It’s probably crawling with electric wires.” She smiled.

“Excuse me for asking, Miss Bloom, but where do you get all the money?”

She smiled a little smile, cryptically feminine, the kind of smile she’d always despised. It succeeded nicely. She smiled again.

“It’s late now,” said Papa, peering out the window. The gloomy clouds were drifting away, gnawing each other spitefully. Papa weighed the hammer in his hand and brandished it at the window. “We can’t start today,” he said, “we have to wait until tomorrow, if that’s okay with you, Miss Bloom.”

“Tomorrow is Friday,” she answered, still smiling. “And my name is Edna.”

He blinked at her, distraught, recalling something faraway, impossible, staring wildly at the swift yellow animal flapping her tail, and Edna was amazed to see that even his eyes were throbbing. Like a giant he towered over her, her narrow waist, her slender thighs, and on the wall outside that led to her entrance some brat, maybe Zacky Smitanka, had scribbled a nasty jingle about a bull and a mouse who want to play house, the coarseness of which estranged them. Suddenly, Papa swerved around, waved his hammer high, and struck a blow at the kitchen wall. Aron shivered in his sleep. The hammer remained at Edna’s over the Sabbath, implanted like an ax inside her wall, where it vibrated uninterruptedly, emitting shock waves in concentric circles.

Mama stood in the kitchen, cooking lunch. Her hands went through the motions like a pair of trusty horses as she sank in contemplation of the sudden turn her life had taken, thanks to a certain Hungarian Miss Eegan-meegan; thanks to her idiot of a husband too, who, like all men, had a tendency to lose his head at the first scent of fresh meat; three weeks, she reckoned, this farce had been going on, sapping her strength, preventing her from attending to any number of tasks; when was the last time she repapered the kitchen cupboards, for instance, or changed the mothballs in the linen closet, or sat down for a talk with Aron; the child was going out like a candle before her eyes, what was happening to him, it wrenched her heart, he would doze for days like somebody’s grandfather, it was having an effect on him, all this, all this … She searched for the appropriate word, but caught a whiff of a strange odor that made her lose her train of thought, and she turned her attention back to the pot in front of her, stirring gradually.

Mama stood in the kitchen, cooking lunch. Her hands went through the motions like a pair of trusty horses as she sank in contemplation of the sudden turn her life had taken, thanks to a certain Hungarian Miss Eegan-meegan; thanks to her idiot of a husband too, who, like all men, had a tendency to lose his head at the first scent of fresh meat; three weeks, she reckoned, this farce had been going on, sapping her strength, preventing her from attending to any number of tasks; when was the last time she repapered the kitchen cupboards, for instance, or changed the mothballs in the linen closet, or sat down for a talk with Aron; the child was going out like a candle before her eyes, what was happening to him, it wrenched her heart, he would doze for days like somebody’s grandfather, it was having an effect on him, all this, all this … She searched for the appropriate word, but caught a whiff of a strange odor that made her lose her train of thought, and she turned her attention back to the pot in front of her, stirring gradually.

Who would have believed it, such a thing happening to us, she sighed, a model family. Mechanically she tasted the soup, added a pinch of salt, stirred joylessly. She had even stopped worrying her head about Edna Bloom in the past few days. If nothing had happened so far, chances were it wouldn’t. Passions are like fruit, she whispered to her image in the shiny pot, pick them when they’re ripe or they rot on the tree. Again she caught a whiff of the unfamiliar odor, impelling her hands to stir more vigorously, and when this is over, and Moshe comeshome with his tail between his legs … she crushed a clove of garlic, added a tablespoon of oil, and began to peel the vegetables for another soup: a vegetarian I’ve got me now, on top of everything, the food I make him isn’t good enough anymore, the boy’s a regular fein-schmecker. He has more pity for a chicken than he does for me here, killing myself to cook his dinner. But then the odor pierced her nose and startled her out of these ruminations.

For a full fifteen years Mama had lived in this dingy-gray building project, and she knew the luncheon menus and baking repertory of the housewives inside out, shrewdly identifying each curlicue of smell in the tangled skein of aromas that wafted out of their kitchens.

So it must have been appalling, a veritable stab in the belly, when these undreamed-of smells infiltrated the familiar ranks, assailing her nostrils with a gypsy effrontery, a fandango of exotic spice. Still ablaze with the memory of her debacle, Mama lost her head, picked up her umbrella, put on her heavy Khrushchev, and walked out the door. Down the stairs to the muddy, neglected garden she hurried, turning left and right. She sniffed the air. Where was it coming from? Dreary gray rain had been drizzling down for the past few days. She flared her nostrils, shut her umbrella so it wouldn’t get in the way, and marched ahead, nose in the air, her goider bulging toadishly till, all at once, in back of the house, she inhaled an aromatic cluster that burst in her nose like a bustling bazaar and filled her heart with foreboding.

Читать дальше

Mama stood in the kitchen, cooking lunch. Her hands went through the motions like a pair of trusty horses as she sank in contemplation of the sudden turn her life had taken, thanks to a certain Hungarian Miss Eegan-meegan; thanks to her idiot of a husband too, who, like all men, had a tendency to lose his head at the first scent of fresh meat; three weeks, she reckoned, this farce had been going on, sapping her strength, preventing her from attending to any number of tasks; when was the last time she repapered the kitchen cupboards, for instance, or changed the mothballs in the linen closet, or sat down for a talk with Aron; the child was going out like a candle before her eyes, what was happening to him, it wrenched her heart, he would doze for days like somebody’s grandfather, it was having an effect on him, all this, all this … She searched for the appropriate word, but caught a whiff of a strange odor that made her lose her train of thought, and she turned her attention back to the pot in front of her, stirring gradually.

Mama stood in the kitchen, cooking lunch. Her hands went through the motions like a pair of trusty horses as she sank in contemplation of the sudden turn her life had taken, thanks to a certain Hungarian Miss Eegan-meegan; thanks to her idiot of a husband too, who, like all men, had a tendency to lose his head at the first scent of fresh meat; three weeks, she reckoned, this farce had been going on, sapping her strength, preventing her from attending to any number of tasks; when was the last time she repapered the kitchen cupboards, for instance, or changed the mothballs in the linen closet, or sat down for a talk with Aron; the child was going out like a candle before her eyes, what was happening to him, it wrenched her heart, he would doze for days like somebody’s grandfather, it was having an effect on him, all this, all this … She searched for the appropriate word, but caught a whiff of a strange odor that made her lose her train of thought, and she turned her attention back to the pot in front of her, stirring gradually.