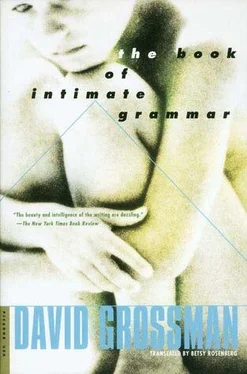

Papa’s magnificent encore lasted forty-five minutes. Edna Bloom leaned forward, staring so hard she seemed to see strange new vistas inside her, cleaved by the blade of a giant plow, or the huge propellor of a ship. Even the noise didn’t disturb her, she who had always slept with cotton flying out of her ears; she who had been taught the secret of Tantra yoga by a gentle Indian student in London some years before but had never dared to take that plunge in her building, because what if, at the supreme moment of silent meditation, when the kundalini serpent rose up from the lowest chakra and wound its way through the five brains to the third eye, the locus of union, she should happen to hear a disturbing shout from a nearby balcony or a toilet flushingsomewhere. She knew now that she was longingly anticipating not merely the reverberation of the sledgehammer in her bowels but everything that went with it: the smell of his exertion, the beads of sweat, and the words exchanged over the past three days among her visitors, and the ensuing silences, all abuzz with secret communications, unintelligible to her; the father, and the son watching him with adoration; and the pudgy teenage daughter glowering at her mother; how wrong she had been about them! She rebuked herself: they had seemed so pathetic to her with their lumpish sheep faces. You were wrong, you were wrong, Edna, see how the air around them shimmers, and learn a lesson from this; maybe you were wrong not only about them but about life itself, about everything, go on, have a good cry, maybe you came close to dying, and maybe you were almost, she gulped and uttered the ghastly word, barren.

In silent gratitude she bowed to Mama, who only turned away. Then she glanced imploringly at Aron, whose eyes widened at her, and her heart soared for a moment, till Mama glared at him, and like a chick warned by the mother bird of approaching danger, he sealed his face to hide the living glow in his eyes, but he blushed for shame. What we have here is a tiny tribe with strict, even pitiless laws — she melted — a violent and repressed civilization. She had not felt such a trembling inside since the day she arranged her National Geographics according to subject and country.

At a quarter to eight that evening Papa flourished his hammer one last time. A snag of plaster, hanging from the ceiling, crumbled down. The wall disappeared and there on the opposite wall was Guernica. Papa stood still, his hammer on his shoulder, studying the picture as though he had just noticed it the first time. Mama took a deep breath. Carefully she folded her knitting. Edna Bloom, worn out and bleary-eyed, could barely sit up in her dusty chair.

“Schoin,” said Mama. “Pay what you owe and we’ll be leaving.”

Papa laid his hammer down and slumped as he hesitated before turning to look at the women.

“I have an idea,” said Edna nervously.

Mama froze.

“I will pay Mr. Kleinfeld another fifty pounds to tear down the other wall as well.” She pointed limply to the second bedroom wall. Withoutso much as a glance at Mama she revealed the wad of moist bills she had been clutching for the past four hours and set them on the table.

Mama looked down at the five-pound notes, with the picture of a muscular farmer holding a hoe, young and virile, staring out at her. “Miss Bloom,” she said, her bosom rising, “I spit on your money.” Never had Aron seen her so red. “There’s something wrong with you, you’re not normal. You let everyone see what’s going on in your head. My husband is a respectable man, Miss Bloom, and what I think is that you should go live in an insane asylum, where you’ll be taken care of.” Aron’s knees began to shake. It wasn’t like Mama to tell strangers to their faces what she usually said behind their backs.

“Sixty pounds, then,” said Edna Bloom, turning to Papa.

“Over my dead body,” said Mama, not budging.

“Seventy.”

Mama gasped. Before her eyes danced fur-lined boots, a new set of dinner dishes to replace the old ones from their wedding that looked as if they came from the flea market, a new steam iron, a modern foam-rubber mattress to replace the straw one, a new marble counter for the kitchen to replace the cracked …

“Your money is dirty,” croaked Mama, never taking her eyes off the moistened wad, which seemed to come to life and reach out to her. “I spit on it,” she muttered weakly, but didn’t spit.

“A hundred,” ordained Edna with astonishing composure.

“If Moshe’s willing. I’m not.” She tottered out the door as scalding tears of humiliation ran down her cheeks, and this was Mama, Mama who would rather die than give anyone the satisfaction of seeing her cry.

Papa gathered up his tools, glanced at Edna with gratitude and stifled excitement, and went out the door, followed by Yochi. Aron remained behind a moment more, obscured between the piano and the wall. Here, this was his big chance to speak to her alone. To confess: I feel so happy in your house, so at home, and you’re nice, pay no attention to what they said to you. It’s only words. But she didn’t even know he was there, she stood with her back to him and began to gasp with laughter. Aron crouched down. She raised her voice again, wreathing herself round with sobs of pleasure, ticklish spasms, as though this laughter could release her very soul. Her wispy yellow hair floated around herface. Aron dared not move. For a moment he didn’t even recognize her. It was as if a stranger in her skin were shaking her. Slowly she calmed herself, raised a slender forefinger, and pointed thoughtfully at the bedroom wall. Then another wall. And another, and another, while endless tears of mirth rained down over her dust-powdered cheeks.

Mama declared she would not set foot in Edna Bloom’s or speak to Papa until he finished the work there. At night Papa took out the scrimpy Gandhi mattress he brought back from reserve duty once and slept in the salon. Mama ordered Yochi to fill in for her at Edna’s, but Yochi had exams coming up, so was excused. I’ll go, ventured Aron cautiously; and Mama gave him a dirty look; she didn’t trust him, maybe she thought he was too young, or then again, maybe she thought he was getting to be too much like Papa. If only he could bring himself to ask her why now, he wouldn’t have to agonize endlessly over that look on her face, but at least she didn’t say he wasn’t allowed to go, and if he went, he would be representing the family.

Mama declared she would not set foot in Edna Bloom’s or speak to Papa until he finished the work there. At night Papa took out the scrimpy Gandhi mattress he brought back from reserve duty once and slept in the salon. Mama ordered Yochi to fill in for her at Edna’s, but Yochi had exams coming up, so was excused. I’ll go, ventured Aron cautiously; and Mama gave him a dirty look; she didn’t trust him, maybe she thought he was too young, or then again, maybe she thought he was getting to be too much like Papa. If only he could bring himself to ask her why now, he wouldn’t have to agonize endlessly over that look on her face, but at least she didn’t say he wasn’t allowed to go, and if he went, he would be representing the family.

How long does it take to tear down a simple wall? About four hours. But how long did it take Papa to tear down the second wall at Edna Bloom’s? Five days. God Almighty, Mama screamed in silence from the Bordeaux sofa, where she lay with an ice pack on her head, that’s enough time to create the earth and the moon with the stars thrown in, and to the neighbors listening outside, Papa seemed to be prolonging every blow, searching for the vulnerable point in the wall, the tender nerve center of wires and pipes and rods, so it would collapse at his feet in perfect resignation. As soon as he arrived each day Edna would serve him a glass of freshly squeezed orange juice, a large glass for him and a small one for Aron. But she isn’t smart like Mama yet, thought Aron, she doesn’t know you’re supposed to cover the glass with a little saucerso the vitamins stay in till Papa gets there, though the juice was no less delicious for that. Papa slurped and gulped while Aron sipped politely to correct the bad impression. “L’chaim,” whispered Edna, beaming a smile, and took the glass from Papa’s hand; a blush spread over their faces, and Papa stammered, Nu, where’s the hammer, and Edna giggled, Here it is, it’s waiting just for you; and before he’d even taken off his shirt, Papa struck a few blows at the wall to hide his embarrassment, or maybe he wanted to show the wall who’s boss, but eventually he relaxed and got into his stride, and Edna swooned in her armchair.

Читать дальше

Mama declared she would not set foot in Edna Bloom’s or speak to Papa until he finished the work there. At night Papa took out the scrimpy Gandhi mattress he brought back from reserve duty once and slept in the salon. Mama ordered Yochi to fill in for her at Edna’s, but Yochi had exams coming up, so was excused. I’ll go, ventured Aron cautiously; and Mama gave him a dirty look; she didn’t trust him, maybe she thought he was too young, or then again, maybe she thought he was getting to be too much like Papa. If only he could bring himself to ask her why now, he wouldn’t have to agonize endlessly over that look on her face, but at least she didn’t say he wasn’t allowed to go, and if he went, he would be representing the family.

Mama declared she would not set foot in Edna Bloom’s or speak to Papa until he finished the work there. At night Papa took out the scrimpy Gandhi mattress he brought back from reserve duty once and slept in the salon. Mama ordered Yochi to fill in for her at Edna’s, but Yochi had exams coming up, so was excused. I’ll go, ventured Aron cautiously; and Mama gave him a dirty look; she didn’t trust him, maybe she thought he was too young, or then again, maybe she thought he was getting to be too much like Papa. If only he could bring himself to ask her why now, he wouldn’t have to agonize endlessly over that look on her face, but at least she didn’t say he wasn’t allowed to go, and if he went, he would be representing the family.