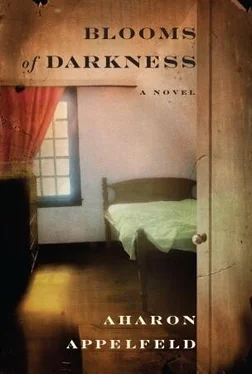

The morning light filters into the closet, drop by drop, and the darkness remains untouched. The hours pass slowly, and hunger oppresses him. This time, too, Mariana is late in coming, and all his attention is focused on his distress, wiping away the clear visions that had moved him during the night.

It isn’t until eleven that Mariana, her face rumpled, appears in a nightgown and hands Hugo a cup of milk.

“I fell deeply asleep, darling,” she says. “You’re probably thirsty and hungry. What have I done, dear?”

“I was thinking about my house.”

“Do you miss it?”

“A little.”

“I would take you out, but everything is dangerous. Soldiers are looking from house to house, and informers are swarming in every corner. You have to be patient.”

“When will the war be over?”

“Who knows?”

“Mama told me that the war would end soon.”

“She’s suffering, too. It’s not easy for her, either. The peasants are afraid to hide Jews in their houses, and the few who do are living in great fear. You understand that, don’t you?”

“Why are they punishing the Jews?” he asks, and he immediately regrets his question.

“The Jews are different. They were always different. I like them. But most people don’t like them.”

“Because they ask when they shouldn’t?”

“Why did you think of that?”

“Mama told me not to ask questions but to listen, and I’m always breaking that rule.”

“You can ask as much as you want, sweetie,” Mariana says, and hugs him. “I like it when you ask me. When you ask me, I see your father and mother. Your mother was my angel. Your father is a handsome man. What luck your mother has, to have a man like that. I was born without luck.”

Hugo listens and senses that envy has sneaked into her voice.

A few days earlier he heard Mariana conversing with one of her friends. “I miss the Jewish men,” she said suddenly. “They were good and gentle. Contact with them was mild and correct. Do you agree?”

“I completely agree.”

“And they always bring you a box of candy or silk stockings, and they always kiss you as if you were their faithful girlfriend. They never hurt you. Do you agree?”

“Absolutely.”

For a moment it seemed to Hugo that he understood what they were talking about. Mariana’s speech was different from anything he had heard at home. She spoke about her body. Rather, she spoke about the fear that her body would betray her.

“Honey, soon we’re going to have to take a bath. The time has come, right?”

“Where?”

“I have a secret bathtub. We’ll talk about it soon,” she says, and winks.

Every few days Mariana forgets about Hugo, and this time she has forgotten about him for many hours. At twelve o’clock she stands at the closet doorway, dressed in a pink nightgown, and looks at him guiltily, saying, “What’s my darling puppy doing? I neglected him. All morning long he’s had nothing to eat, and he’s certainly hungry and thirsty. It’s all my fault. I slept too much.”

She quickly hurries to bring him a cup of milk and a slice of bread spread with butter. The warm milk is quickly swallowed.

“Have you been awake for many hours? What were you thinking about?”

“I was thinking about my uncle Sigmund.” Hugo doesn’t hide it from her.

“Poor guy, a good man.”

“Did you know him?” Hugo allows himself to ask.

“Since my childhood. He was handsome, and a genius, too. Your mother was sure he’d become a professor at the university, but he became enslaved to drink and destroyed his life. Too bad about him. He was a good uncle, right?”

“He always brought me presents.”

“What, for example?”

“Books.”

“Sometimes he would come to me, and we would talk and laugh. He always made me laugh. Where is he now?”

“He’s in a labor camp with Papa,” Hugo answers quickly.

“I liked him very much. I even dreamed about marrying him. You’re still hungry. I’ll bring you some sandwiches.”

Hugo likes the food that Mariana brings him. In the ghetto food was scarce. His mother did everything possible and even the impossible to prepare meals from nothing. Here the food is tasty, especially the sandwiches. Because of the sandwiches, the place seems to him like a big restaurant where people come from all over the city, like Laufer’s restaurant, where his parents went on his birthday and on his mother’s birthday. His father refused to celebrate birthdays.

After eating the sandwiches, Hugo asks, “Is there a school here?”

“I already told you. There is one, but not for you. You’re in hiding now with Mariana until the end of the war. Children like you have to hide. Are you bored?”

“No.”

“In the afternoon, we’ll take a bath. The time has come to take a hot bath, right? But meanwhile I brought you a little present, a cross to wear around your neck. I’ll put it on you right away. That will be your charm. The charm will protect you. You mustn’t take it off either by day or by night. Come here, and I’ll put it on you. It suits you very well.”

“Do all the children here wear crosses?”

“Certainly.”

Hugo feels the way he felt on the day he was called up to the blackboard to get his report card from the teacher. The teacher said, “Hugo is a good pupil, and he will improve.”

It turns out there is a bathroom behind the cupboard in Mariana’s room. The bathroom is wide and luxurious, with little cupboards, a dresser, a mat, soap bars of every color, and bottles of perfume.

“I’ll bring two pails of boiling water. We’ll add cold water from the faucet, and we’ll have a bath from paradise,” Mariana says in a festive tone.

Hugo is stunned by the colors. It is a bathroom, but different from any he’s ever seen. The ostentatious luxury says that here people do more than take baths.

In a few moments, the bathtub is full. Mariana touches the water and says, “Marvelous water. Now get undressed, my dear.” Hugo is astonished for a moment. Since he was seven, his mother had stopped washing him.

Mariana, seeing his embarrassment, says, “Don’t be ashamed. I’ll wash you with perfumed soap. Plunge in, dear, plunge in, and I’ll soap you down right away. You start by plunging in, and only afterward you soap yourself.”

The embarrassment evaporates and a strange pleasantness envelops his body.

“Stand up now, and Mariana will soap you from your feet to your head. Now the soap will do wonders.” She soaps him and washes him hard, but it’s a pleasant hardness. “Now plunge in again,” she orders. In the end she pours tepid water on him and says, “You’re good. You do everything Mariana tells you to do.”

She wraps him in a big, fragrant towel, puts the cross around his neck, looks at him, and says, “Wasn’t it nice?”

“Excellent.”

“We’ll do it often.”

She kisses his face and neck and says, “Now it’s night. Now it’s dark. Now I’ll lock you in your kennel, honey. You’re Mariana’s, right?” Hugo is about to ask her something, but the question slips out of his mind.

Mariana says, “After a bath, you sleep better. Too bad they don’t let me sleep at night.”

Why? he is about to ask, but he stops his tongue in time.

That night is quiet. Though he does hear voices from Mariana’s room, they are muffled. He can feel the chilly darkness and the thin night lights that filter through the cracks between the boards and make a grid on his couch.

The bath and the cross that Mariana put around his neck seem to mingle into a secret ceremony.

Both gestures gave him pleasure, but he doesn’t understand what is visible here and what is a secret.

Читать дальше