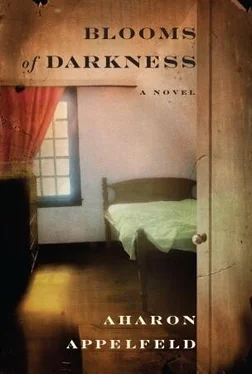

Aharon Appelfeld

Blooms of Darkness

In memory of Gila Ramraz Rauch

Tomorrow Hugo will be eleven, and Anna and Otto will come for his birthday. Most of Hugo’s friends have already been sent to distant villages, and the few remaining will be sent soon. The tension in the ghetto is great, but no one cries. The children secretly guess what is in store for them. The parents control their feelings so as not to sow fear, but the doors and windows know no restraint. They slam by themselves or are shoved with nervous movements. Winds whip through every alley.

A few days ago Hugo was about to be sent to the mountains, too, but the peasant who was supposed to take him never came. Meanwhile, his birthday approached, and his mother decided to have a party so Hugo would remember the house and his parents. Who knows what awaits us? Who knows when we will see one another again? That was the thought that passed through his mother’s mind.

To please Hugo, his mother bought three books by Jules Verne and a volume by Karl May from friends already marked for deportation. If he went to the mountains, he would take this new present with him. His mother intended to add the dominoes and the chess set, and the book she read to him every night before he went to sleep.

Again Hugo promises that he will read in the mountains and do arithmetic problems, and at night he will write letters to his mother. His mother holds back her tears and tries to talk in her ordinary voice.

Along with Anna’s and Otto’s parents, the parents of other children, who had already been sent to the mountains, are invited to the birthday party. One of the parents brings an accordion.

Everybody makes an effort to hide the anxieties and the fears and to pretend that life is going on as usual. Otto brought a valuable present with him: a fountain pen decorated with mother-of-pearl. Anna brought a chocolate bar and a package of halvah. The candies make the children happy and for a moment sweeten the parents’ grief. But the accordion fails to raise their spirits. The accordion player goes to great lengths to cheer them up, but the sounds he produces only make the sadness heavier.

Still, everybody tries not to talk about the Actions, or about the labor brigades that were sent to unknown destinations, or about the orphanage or the old age home, whose inmates had been deported with no warning, and of course not about Hugo’s father, who had been snatched up a month before. Since then there has been no trace of him.

After everyone has left, Hugo asks, “Mama, when will I go to the mountains, too?”

“I don’t know. I’m checking all the possibilities.”

Hugo doesn’t understand the meaning of “I’m checking all the possibilities.” He imagines his life without his mother as a life of attention and great obedience. His mother repeats, “You mustn’t act spoiled. You have to do everything they ask of you. Mama will do her best to come and visit you, but it doesn’t depend on her. Everybody is sent somewhere else. Anyway, don’t expect me too much. If I can ever come, I will.”

“Will Papa come, too?”

His mother’s heart tightens for a moment, and she says, “We haven’t heard from Papa since he was taken to the labor camp.”

“Where is he?”

“God knows.”

Hugo has noticed that since the Actions his mother often says, “God knows,” one of her expressions of despair. Since the Actions, life has been a prolonged secret. His mother tries to explain and to soothe him, but what he sees keeps telling him that there is some dreadful secret.

“Where do they take the people?”

“To labor.”

“And when will they come back?”

He has noticed. His mother doesn’t answer all his questions the way she used to. There are questions she simply ignores. Hugo has learned meanwhile not to ask, to listen instead to the silence between the words. But the child in him, who just a few months ago went to school and did homework, can’t control itself, and he asks, “When will the people come back home?”

Most days Hugo sits on the floor and plays dominoes or chess with himself. Sometimes Anna comes. Anna is six months younger than Hugo, but a little taller. She wears glasses, reads a lot, and is an excellent pianist. Hugo wants to impress her but doesn’t know how. His mother has taught him a little French, but even at that Anna is better than he. Complete sentences in French come out of her mouth, and Hugo has the impression that Anna can learn whatever she wants, and quickly. Unable to think of an alternative, he takes a jump rope out of a drawer and starts skipping rope. He is better at hopping than Anna. Anna tries very hard, but her ability at that game is limited.

“Did your parents find a peasant for you already?” Hugo asks cautiously.

“Not yet. The peasant who promised to come and take me didn’t show up.”

“My peasant didn’t show up, either.”

“I guess we’ll be sent away with the adults.”

“It doesn’t matter,” says Hugo, bowing his head like a grown-up.

Every night Hugo’s mother makes sure to read him a chapter from a book. Over the past few weeks, she has been reading him stories from the Bible. Hugo was sure that only religious people read the Bible, but, surprisingly, his mother reads it, and he sees the images very clearly. Abraham seems tall to him, like the owner of the pastry shop on the corner. The owner liked children, and every time a child happened into his shop, a surprise gift awaited him.

After his mother read to him about the binding of Isaac, Hugo wondered, “Is that a story or a fable?”

“It’s a story,” his mother answered cautiously.

Hugo was very glad that Isaac was rescued, but he was sorry for the ram that was sacrificed in his place.

“Why doesn’t the story tell any more?” asked Hugo.

“Try to imagine,” his mother advised him.

That advice turned out to work. Hugo closed his eyes and immediately saw the high, green Carpathian Mountains. Abraham was very tall, and he and his little son Isaac walked slowly, the ram trailing behind them, its head down, as if it knew its fate.

The next night a peasant came and took Anna away with him. Hugo heard about it in the morning, and his heart tightened. Most of his friends were already in the mountains, and he remained behind. His mother kept telling him that a place would soon be found for him. Sometimes it seemed to him that children were no longer wanted, and that was why they were sent away.

“Mama, why are they sending the children to the mountains?” He can’t stop his tongue.

“The ghetto is dangerous, don’t you see?” She is curt.

Hugo knows that the ghetto is dangerous. Not a day goes by without arrests and deportations. The road to the railway is crammed with people. They are burdened with heavy packs, so heavy that they can hardly move. Soldiers and gendarmes brandish their whips over the deportees. The miserable people are shoved and collapse. Hugo knows now that his question, “Why are they sending the children to the mountains?” was foolish, and he is sorry he hadn’t been able to restrain himself.

Every day his mother equips him with short instructions. She repeats one directive: “You must look around you, listen, and not ask. Strangers don’t like it when you ask them questions.” Hugo knows his mother is preparing him for life without her. He has had the feeling that over the past few days she has for some reason been trying to keep him at a distance. Sometimes her strength fails her, and she weeps and moans.

Otto sneaks in to play chess. Hugo is better than Otto at the game, and beats him easily. Seeing his defeat, Otto raises his hands and says, “You won. There’s nothing to do.” Hugo is sad for Otto, who doesn’t play well and doesn’t even notice a simple threat. He consoles him and says, “In the mountains you’ll have time to practice. And when we meet after the war, you’ll be well trained.”

Читать дальше