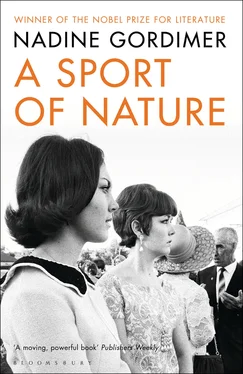

Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Bloomsbury UK, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Sport of Nature

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury UK

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Sport of Nature: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Sport of Nature»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Sport of Nature — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Sport of Nature», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In many ways it was more than the distance of a back yard from the house to Alpheus’s garage. It was the only outing they took, that Saturday. Hillela did not use the telephone. This was a day before them, all around them, untouched either at beginning or end by the week that preceded it or the week that would follow when on Sunday night, familiarity, a family would return. The luxury of its wholeness extended the ordinary course of a day, measured time differently, as Hillela’s breath had measured it in the night. The cat followed and stayed with them everywhere, perhaps only because they did not know it was accustomed to getting trimmings from Bettie. It kneaded Sasha’s thighs and Hillela kissed one by one the four sneakers of white fur for which it had got its name, Tackie. What they took for affection, weaving them into its caresses, was only greed. They themselves did not touch. There were several chess lessons that ended in laughter, they even quarrelled a little; it was impossible to have Hillela to oneself, at one’s mercy, without frustration at her lack of adolescent apprehension, envy of her — what? Adults begin to predicate from the time children are very small. What do you want to be when you grow up? What are you going to do when you leave school? What career are you interested in? This predication was not an answer to anything about life it was needed to know. These questions, formulae put absently by men and women preoccupied by financial takeovers, property speculation, divorces, political manoeuvres, Sasha knew were lies. From the beginning: —They knew you were never going to be an engine driver … not if they could help it. They despise engine drivers. They know it’s not what you want to be , it’s what they’ve already decided you’ll settle for, so they can say they’ve done all they could for you.—

— You should do whatever you want to do.—

— Can’t you understand?—

— You wrangle away at it too much. You’ll get hungry, you’ll have to eat; you’ll have to work.—

— I don’t understand you. You’re the one who’s had a lousy time, you’ve been pushed around as it suited them, and you — I don’t know … you seem to feel free. No-one’s less free than you! What’s going to happen when you leave school next year? Are they going to pass the hat round to send you to university?—

— Now don’t be unfair, you know they would.—

— Or are they thinking that for you it’s a secretarial course and a useful job through influence at the Institute of Race Relations, and someone will pay for a degree by correspondence, on the cheap, like for Alpheus.—

— Well, maybe I’ll go to Rhodesia.—

— You’ve just thought of that for something to say, this minute.—

She laughed; they were eating apples and the juice trickled down her chin.

— Maybe I’ll get a job.—

— What job?—

— Oh journalism, or maybe nursing.—

— For pete’s sake! The difference is … tremendous, total. You’d think it was choosing between chocolate or vanilla. When do you suppose you’ll decide?—

— Then. I’ll say, then. Nursing; newspaper.—

— Hilly, Rhodesia’s a horrible place, there’s going to be a war there.—

— Len never says anything.—

— When he writes you a birthday card, no.—

With regular bites, she was shaping a spool out of the apple core.

— Sasha … Why d’you let everything make you so angry. Sasha …—

He felt a fresh surge of what she called anger. — Because you forgive them.—

The castaway raft that was carrying the day dropped out of rapids into quiet water. She played the guitar to herself, bent over cradling it to save him from disturbance. Out of his week’s pay at the liquor store he had bought himself some books, and had begun one this weekend. The Brothers Karamazov was in the house in the old red hardback uniform edition of Dostoevsky along with all the other books under whose influence he had been reared without knowing it or having read them, but he had bought the paperback as if the other had not been there all his life, on one of the shelves that narrowed every passage as well as stretched up the walls in every room, and made the odours he associated with home compound with the smell of paper and the livingroom fruit bowl. He wanted to read the book because he had heard one of the masters at school mention, in a debate on capital punishment (the school tried hard to introduce issues that schoolboys could not be expected to think about), that the writer Dostoevsky had stood before a firing squad and found himself suddenly reprieved instead of dead. The extremity of this experience attracted Sasha, who sometimes was secretly drawn to the possibility of committing suicide. One of the reasons for the anger which Hillela had gently mocked was that he felt his mother had wormed this secret out of him — not in words, but in the concentration of signs only she and he could read: the way he left a room, the shift in his attention when someone was speaking — he could not stop her adding these things up. But he was safe from that secret now. Hillela was there. It was not possible to think of nonexistence while she was close by, her bare foot with the one funny toe stretched towards the afternoon fire they had made for themselves.

He was disappointed with the visit to the holy Zossima (rationalism was one of the influences he was unaware of; religious mysticism bored him) until Fyodor Pavlovitch Karamazov embarrassed his sons by making a ridiculous scene, but after that the new reader entered the novel as millions had done before him, although to him it seemed its knowledge of all he needed to know, that nobody would ever tell him — even though everything was discussed, talk never stopped — was part of the possession of the house boarded this silent weekend when it was lit-up and empty. As he read his absorption deepened like the stages of sleep; and he was aware of his companion only the way the cat, actually asleep, showed awareness of the comfort of human presence and the fire’s warmth by now and then flexing thorns through the white fur of a paw. Then he fell into a passage that seemed to surround and isolate him. ‘I am that insect, brother, and it is said of me specially. All we Karamazovs are such insects, and, angel as you are, that insect lives in you, too, and will stir up a tempest in your blood. Tempests, because sensual lust is a tempest! Beauty is a terrible and awful thing! It is terrible because it has not been fathomed and never can be fathomed, for God sets us nothing but riddles. Here the boundaries meet and all contradictions exist side by side. I am not a cultivated man, brother, but I’ve thought a lot about this. It’s terrible what mysteries there are!’

He did not know Hillela had stopped playing her guitar; he had not been listening. She wandered out of the room, and that she was not there any longer he felt immediately. He thought he heard her calling. Some other sound, the susurrus of the shower; perhaps he imagined the voice, like the voices heard under a waterfall. He went to the bathroom door and rapped a mock drum-roll. She did call something. He rapped again. Hillela opened the door, pink paths showing all over her drenched head, streams of water licking her breasts, the springy stamens of her pubic hair brilliant with shaking drops. A hollow of pale mauve shadow went from each lean hip-bone down to the groin. — I boiled myself by the fire. — He looked at her. Not at her face; and she was watching him, both encouraging and anxious, a kind of happiness. He kissed the breasts, letting them wet his face. He knelt down and pressed closed eyes and mouth against that wet moss that poor boys at school had tried to represent in ugly drawings in the lavatories. She reached for a sponge and squeezed it over his head. The water ran down his hair and plastered it. She teased: —Just like an old mango pip. — They played, through the open door the house was filled with shouts and laughter. The shower was still plashing. They fought and slithered in the steam. She pulled him under the fall of water and he struggled out of his wet clothes and imprisoned her, cool and ungraspable. The water found the meeting of their bellies and poured down their thighs. She la-la-la-ed, he pushed her head under the full force of the jet.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Sport of Nature» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.