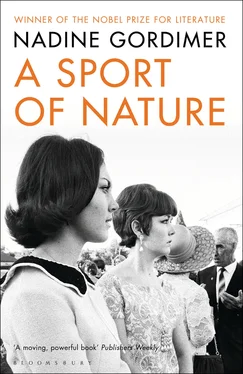

Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Bloomsbury UK, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Sport of Nature

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury UK

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Sport of Nature: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Sport of Nature»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Sport of Nature — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Sport of Nature», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

To the young people, Pauline added an awkward rider to her warning. — Nothing —to anyone. Is that clear? Not to any of my friends, either.—

This time Pauline had not refused succour; and the man who sought it was not one of those whom she ‘supported’. She had known this Donsi as a young black party-goer at white houses. Everybody knew him, then; a messenger in some editorial office who tagged along with those favoured invited guests, black journalists, for the free drinks, and paid for his presence by his ability to enjoy himself and generate in his hosts the pleasure of getting on well with blacks. He was (to the perception of whites, anyway) too much of a fat and happy light-weight to be of use in the political struggle, which in those circles meant the African National Congress. His name began to come up as a regional leader of those who left the Congress because they did not want to mix with whites until, they said, white power was broken; it was only later it was noticed he wasn’t at parties any longer. His people did not want to dance or sit with whites. But she had found him dancing with her daughter and niece; and she had risked arrest by driving him and his family to a place near the border where someone was waiting to smuggle them across. Donsi Masuku had learnt from a relative in the political branch of the police (there were family connections who betrayed, there were family connections who saved) that he was about to be rearrested and charged, this time in a major trial for treason. What she had done was not something she could explain to friends with whom she supported the African National Congress, and who (no doubt) had heard of her failure to give asylum in a context she might be expected to. Joe had witnessed; but Joe would riot confront her with the paradox. Joe could not, because he himself never would share her fierce faction partisanship or her ferocious doubts: Joe (as she taunted him) defended all who needed defence against a common evil.

As one who has strayed feels a rush of strong and relieved attachment to a permanent liaison, Pauline wanted to be continually among these friends, now. She did not ask Joe to calculate the risk she had taken as opposed to those she had refused; but he volunteered nothing to reassure her that the police might not discover the number of the car that assisted a black man to leave the country illegally. She knew from his silence that the risk existed. The company of friends was something she needed to wrap around herself against dread. Although it was school holidays and she and Joe made it a rule to be at home when their son was, she accepted the chance to go away with friends for a weekend; Carole did not work on Saturdays and would come along, but the other two had the obligation of their jobs to fulfill. It distressed Pauline that Sasha disliked his holiday occupation so much; that she had been too preoccupied to help him find something interesting. She confided him to the care of adaptable Hillela. — Take Sasha along when you and your friends go out. Don’t let him know I asked you.—

The house to themselves. Children with the house to themselves. When they were still children, what wild release that signalled; romping from room to room, all lights burning, bedtime banished, the thrills of outlawry within the safety of home: Bettie’s protests to scatter them, shrieking, only to recommence the game of freedom, because her authority was no more founded than the game.

On Friday night after Pauline, Joe and Carole had left, Bettie cooked the meal of chops and chips (Sasha’s favourite long ago) for which Pauline had left instructions. Hillela sat on the floor untidily as a rag doll propped there, telephoning, all animation gathered into her chance to talk without interruption from others wanting to use the phone. She was making arrangements to go out; Sasha knew. He went away to some other part of the house so as not to listen to another’s conversation. But she did not go out.

Sasha?

He heard her looking for him.

Sasha? Sasha?

She was in the garden, now. He went to his mother’s room, which overlooked the direction of the voice. From the silent observation of the room that held the humming continuum of Pauline and Joe’s lives, he saw her shadow sloping away from her. He waited to hear her call again.

— Sasha?—

The cat came running, as it would to anything that sounded like a summons to food or fondling. Their shadows joined where she stooped to chide and croon to it for being so stupid. He opened the closed window that marked absence and jumped. Out of the stiff cold oleander bushes whose dead leaves smoothed past his legs like blunt knives, his shadow joined hers and the cat’s. For a while the angled, elongated mobile that was the three shadows jazzed, darted, and leant towards and away from the tilted phantom of the house, all cast over the dead lawn by the light of stars in a spill of cracked ice across the sky. The cat’s eyes, as she drew the pair into one of her zany night ecstasies, were moons, rather than the new sliver lifted too high and far in the black clarity of space. Their round phosphorescent gold, the flash of translucence as she pranced in profile, were the moons of summer, the nights of the smell of burning flesh from suburban braaivleis. Then she was gone.

Sasha had on his sweater but like most young males who live in a climate of long summers and never accept the brief reality of winter, he wore about the house, in all seasons, the same shorts and rubber-thonged sandals. The cold steeped his legs palpably as water; Hillela puffed out a breath to see it hang in air. They went through the gate, each with arms crossed, hugging self, and began to walk; to walk the streets of the suburb as people are brought out by a summer night. Block after block; they passed through the planes, bared horizontals and verticals stripped by winter; only among the pavement jacarandas, that do not shed their leaves till spring, each streetlight swam, a luminous fish in a cave of green hollowed out of the night. Although when the three young people were together, or with friends, the adolescent fidgety abhorrence of silence, the need to talk because one is alive, possessed them, the two did not talk much. Hillela hummed one of her guitar tunes now and then. When they did exchange a remark, a phrase or a laugh shattered the clear cold like a stone thrown. At times there was the feeling, in the rhythm of their progress, that they might be making for somewhere, but neither said, nor asked of the other, where; at others (when a corner was reached), that they were looking for a destination. There was none; or none other. They arrived back at the gate. All the lights were burning in the house, except in Pauline and Joe’s bedroom, where a window stood open. Bettie had not locked up, knowing there was no-one to reproach her neglect. The house was one of those legendary ships that sail on, fully rigged, without a living soul aboard.

They stamped in, Hillela putting her hands, warm from her pockets, over red-cold ears. Now she would go to the telephone, now she would put on lipstick, fluff her hair with her fingers and leave him there … Now he waited for her to come and call goodbye. She appeared with a pair of his soccer socks on over her jeans, threw a second pair for him to catch. — Don’t worry, I haven’t been rummaging into any of your things. They weren’t put in your room yet, they were among stuff Rebecca’s washed.—

The house to themselves. Even the children had slipped away for ever in the adult silences of a night walk. He offered: —D’you want a fire?—

— Too much fag to go out for wood.—

— I feel like a drink.—

— Okay, I’ll make tea. Coffee?—

— I mean a drink. What about you?—

But without waiting for her to say, he went to take a bottle of wine and forgot the glasses. She brought the first thing she saw in the kitchen, two cocoa mugs. — Hillela!—

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Sport of Nature» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.