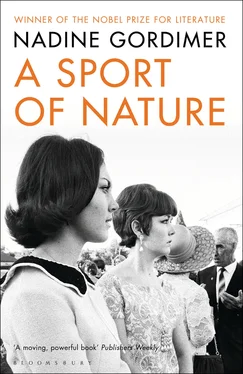

Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Bloomsbury UK, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Sport of Nature

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury UK

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Sport of Nature: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Sport of Nature»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Sport of Nature — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Sport of Nature», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

— It’ll taste the same.—

He went for glasses. Smiling, she watched him open the bottle. — You’re supposed to wipe the rim.—

— Why, it’s not dirty.—

— I don’t know. They always do at Olga’s. And Arthur sniffs it first.—

— And what’s that in aid of.—

— To see if it’s corked.—

He filled the glasses. — The education you’re getting — what a great start in life.—

Hillela took his sharpness kindly, with enjoyment. Her cheekbones, dusky-red with cold, lifted under her strange shining eyes, whose iris, he had examined and explained to her, had no grain to differentiate it from the dark pupil. — At least I’m learning to drive.—

— But you ought to get your learner’s licence, you know. I suppose you’re driving around illegally all over the place.—

— In what?—

— Your friends let you, I’m sure.—

Hillela was always in command of the subject; changed it at will. — Teach me to play chess.—

He looked at her. — Now?—

— Yes.—

He drank, drew a note sounded from the glass with thumb and forefinger, didn’t look at her.

— What for?—

— To play, of course. Oh you think I’m too stupid.—

At once his face was sullen with anxiety. — You are not stupid, Hillela. — He moved his head as if tethered somewhere; and broke loose. — You are the most intelligent person in this house.—

She laughed, made an exaggerated movement pretending to spill her wine. — There’s no-one here except you!—

— And it’s true.—

— Then only you think so. — At once she turned away quickly from what she had said. — Come on. We’ve got all night.—

They took the bottle and went into Joe’s study, intending to fetch the beautiful chess set that was kept on a filing cabinet, but instead of returning to the livingroom settled themselves there, with the radiator turned on and the wine at hand, in that single room in the house that was never for general use, where Bettie was not even allowed to dust because of the importance and confidentiality of the papers and documents filed and piled within it. They lifted the legs of the burdened desk and pulled from beneath it the sheepskin foot-rug, to sit on; they dumped the papers from a stool to make of it a low table between them. Given in, Sasha was explaining to her. — It’s too abstract for you. You’ll learn, all right. But you’ll only want to play when there’s nothing else to do. And that’s not what chess is. How shall I say — you’ll always be wanting to do something else.—

She was setting up the men, an Africanised set made of malachite in Rhodesia (maybe even exported by her father, who at one time had dealt in curios). — I don’t want to do something else.—

In the small hours, the child abandoned in the dark and cold came back to possess a body again for a moment. Sasha woke to some awful interruption; he had the sensation of terrible discovery and disbelief he had had when, for a period when he was already around eight years old, he would find he had wet the bed. But it was a regular slamming, and not a physical sensation, that had wakened him; his bed was dry, he was not alone, there was the wonderful heavy warmth of breasts against him, and the passing time that brought him to consciousness was measured by the gentle clock of another’s breathing. Hillela was there. There was nobody else. He got up and went, knowing his way in the dark in this empty house, to that bedroom where the window had been left open and was banging to and fro in the wind.

Her charges had cooked breakfast for themselves when Bettie pushed the kitchen door open with the armful of pots and dishes brought back from her man’s dinner the night before. She was satisfied rather than pleased. — You old enough now not to make such a mess! — She washed up for them, her reproaches affectionate, a routine assertion of her field of efficiency. Although Hillela was like a daughter in the house, she did not have quite the proxy authority to give Bettie the day off. Sasha told her she needn’t bother, he and Hillela would find their own food. — And tonight? For dinner? — It’s Saturday. We’ll be out. Saturday night, Bettie. — She swept eggshells into the bin, laughing. — Him? When do you ever go out dancing? Hillela, she’ll be having a good time, but you … Sasha … You afraid of the girls, I’m sure. — Not a man, to her, yet the white man in the house, for that weekend: —Please, Sasha, go and see what’s wrong in Alpheus’s place. There’s no light, the water’s not hot, nothing. She can’t warm the food for the baby.—

— Probably a fuse blown, that’s all. I think there’s a box of wires in the broom cupboard. You know, on that small shelf. Alpheus can replace it himself.—

— No, no, you must go. If he messes something up, who is it going to be in trouble? Me, that’s the one.—

— You’re a terrible nag. Why can’t you trust Alpheus?—

— Because Alpheus he’ll sit there with candles and he won’t ask! Won’t say nothing! I’m the one, for everybody. Must speak for everybody.—

Sasha was throwing corks and broken kitchen utensils out of a drawer, looking for the fuse wire.

— Oh you are good to me. Thanks, eh. Thanks, Mouser. — To be called by that name was to meet with blankness someone who makes the claim in the street: Don’t you know me? It was himself, Mouser , one of the many pet names of childhood that evolve far from their origin, in the manner of Cockney rhyming slang. It might have had something to do with big ears, with a liking for getting into small closed places, with pinching cheese, or the cat-like patience and curiosity of a solemn small boy. Even his mother, who had so many such names to express her delight in him then, would have forgotten, in her loss of so much that had been between them. That Bettie was still allowed to bring it out incongruously was more a mark of condescension to her than a privilege accorded. Despite her house-training in awareness of her own dignity, she had her lapses into the manner of Jethro, which perhaps needed less of an effort against the grain of their identical definition as servants.

The absent Carole went in and out of what was now the home of Alpheus and his family, and often brought the baby over to the main house. She and Alpheus’s girl made clothes for it on Pauline’s sewing machine that Carole had taken to the garage. Sometimes she shared a meal there. But Hillela showed no interest in the inhabitants across the yard, and Alpheus was some sort of issue between Sasha and his mother that nobody but the two of them was aware of; when he came home for holidays there was expectation that he would go to talk to Alpheus as he liked to renew acquaintance each time with all that was familiar.

— What about? — He knew she naturally assumed that the kind of school community he was privileged to live in must provide an ease of communication with the young man she herself could not have. She wouldn’t say it, but he wouldn’t let her off. — I live with black boys all the time, I’ve got nothing particular in common with Alpheus.—

Neither he nor Hillela had been in the garage since it had become a family home. Frilly curtains on a sagging wire, smell of burned cooking and the sweetish cloy of confined human occupation, a hi-fi installation hanging the festoons of luxury over napkins, bed and cooker — its existence became real around their presence as strangers; bringing a sense of this not only here, but in the house across the yard where they had moved in from night streets.

Alpheus was a soft-voiced helper as he and Sasha dismantled a single electrical outlet whose plastic had melted and melded with the overload of plugs connected through an adaptor. — You need a separate outlet now that you have a hi-fi as well. They’ll have to get an electrician to install another lead from the main. — Alpheus took the advice as if it were something he could follow in the practical course of things. But both knew he had bought what he did not want his benefactors to know about, because he had no business spending money on such things as hi-fi equipment, any more than he should have burdened himself with a family. Alpheus’s girl hanging about in the background acknowledged Hillela with the same gazing politeness — gone completely still, as if in the children’s game where the leader turns suddenly to confront those moving up secretly behind him — that she had had when the white girl, carrying torn-up letters, had come upon her carrying her pregnant belly in the yard. The girl was wearing one of Carole’s favourite dresses Hillela now realized she had not seen for some time; she had worn it herself, she and Carole often exchanged clothes. There was something else whose disappearance she had not noticed. In the little home where the functions of all rooms were reduced to fit into one, there were no ornaments except a few plastic toys and, on a straw mat on the hi-fi player, the undamaged Imari cat.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Sport of Nature» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.