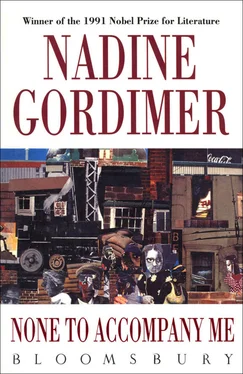

Nadine Gordimer - None to Accompany Me

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - None to Accompany Me» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Bloomsbury Paperbacks, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:None to Accompany Me

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Paperbacks

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

None to Accompany Me: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «None to Accompany Me»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

None to Accompany Me — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «None to Accompany Me», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Mrs Stark put her notes into the sling bag, assuring that she would find her way back to the city. Without the face of a resident in black areas as escort beside her, she took the precaution of locking the car doors and closing the windows. Moving in a capsule; neither what usefulness her notes will be to the case nor the letter lying beneath the notebook dispelled the unreality of the place just left behind. She was accustomed to squatter camps, slum townships, levels of existence of which white people were not aware; the sudden illusion of suburbia, dropped here and there, standing up stranded on the veld between the vast undergrowth of tin and sacking and plastic and cardboard that was the natural terrain, was something still to be placed.

She had an urge to pull over to the roadside and read the letter.

But it was a resort to distraction; just as having to go about her business to somewhere named Phambili Park had served as a reason to thrust the letter half-read into her catch-all bag. And you don’t stop for any reason or anyone on roads these days. With one hand on the wheel, she delved into the bag to feel for the envelope. Ivan a frowning child her own frown of attention always looking back at her from him his habit of fingering his nose while he talked (don’t do it, it’s ugly) at the butcher’s I never knew our brains was like that a carriage lamp to shine out over the grey spill—

She found she was at the turn-off to the hospital where the soft-voiced witness had said people from the squatter camp had taken refuge. So she drove into the hospital grounds, waved on by security guards, and brought the car to a standstill. But not to read a letter.

She trudged over raked gravel between beds of regimented marigolds towards the wings of the hospital, dodging the hiss of the sprinkler system. Pigeons waddled to drink from the spray; a two-metre-high security fence under the hooded eyes of stadium lights surrounded this provincial administration’s hallucination of undisturbed ordinance. All along the standard red-brick and green-painted walls of the hospital people were collected as if blown there as plastic bags and paper were blown against the fence. Women sat on the ground with their legs folded under skirts and aprons, small children clinging and climbing about them. Men hunched with heads down on their knees, in a dangling hand a cigarette stub, or stood against the walls; looked up from staring at feet in broken track shoes advertised for the pleasures of sport. She greeted some groups; they blinked listlessly past her. She made a pretext for her approach, Were there people living in the hospital? An old woman took a pinch of snuff and pointed while she drew it up her nostrils. Are you sleeping there? A woman tugged at the blanket tied cutting into the shape of her sturdy breasts, needing to accuse anyone who would listen. — They tell us no more place. Here! We sleeping here!—

Out of the stasis others were attracted. They didn’t seem to understand questions in English or Afrikaans — Mrs Stark knew from experience how people in shock and bewilderment lose their responses in confusion, anyway — but the woman in the blanket spoke for them. — Five days I been here. What can I do? That night those shit take eveything, they kill — look at this old man, no blanket, nothing, the hospital give him blanket, when he’s run those men catch his brother, TV, bicycle, everything is gone from his place — shit!—

The man was coughing, his knees pressed together and shoulders narrowed over his chest, folding himself out of the danger of existence; the babies sucked at breasts, greedily taking it on.

— And this woman, she try to go to her home yesterday, in the night she come back again. No good, terrible—

The woman had the serene broad face that at the end of the twentieth century is seen only on young peasants and nuns, she will have followed her man from some Bantustan to the city that had no place for her, but neither the squatter camp nor the flight from it had had time to redraw the anachronism of her face in conformation with her place and time. She didn’t yet have the tough grimace pleated round the eyes and the stiff distended nostrils of the woman, a creature of prey, who was displaying her.

She prepared herself obediently to speak. A hump under cloth on her back was a baby. A small girl hid against her thick calves. — Friday there by Phambili where we living they come to get my husband. We run away but there’s plenty people running, night-time, and I don’t see where is my two children, the boys children, I was running with the small ones like this— (raised hands towards her back, carrying the weight) — now I don’t see my two children when I’m come to this hospital. Now yesterday I think I must go back to my house and see where is my children, my boys children, but when I come in the veld I see those men again they by my place—

She looked to others, someone, to find words for this sight, an explanation, what to do.

Were they hostel men, did they carry knobkerries, knives, how were they dressed?

The woman pulled the baby’s legs more securely round her waist and took again the long breath of her panic as she fled dragging her children into the veld, how could she be sure what she saw, how could she know anything but the urgency of her flesh and the flesh of her children to get away.

What about you — you get a chance to see who they were, the men who came that night?

The woman with the blanket stood before Mrs Stark on bare planted feet. — Me? You say what you see, your house is burn down or they kill you. Better I see nothing. — A fly was creeping round her cheek under the eye. Too much had happened for her to notice so small a predator treating her as if she were already a corpse.

And the letter. Lying at the bottom of the sling bag under the notes, under the sign of spilt brains and carriage lamp and the people staring for salvation, becoming dark clusters and clumps along a wall as she walked away from them.

When she got home — it was too late to go back to the Foundation — she came upon the letter. She was alone in the house that was hers as the bounty of divorce, in an order of life that could take for granted rights and their material assurances — her normality. It’s always been her house; Ben moved in with her, first as lover, then husband. It contains tables, lamps, posters and framed photographs, worn path on a carpet, bed — silent witness to that normality.

She leant against the windowsill, where there was still sunset light. The handwritten address directed to the Foundation was itself part of the text waiting to be read. Why does he tell me and not his father?

Why did he know — think — she would understand better? The envelope written in the well-rounded upright script she had seen form from his kindergarten alphabet, sent to a clandestine address like a love letter; a claim to share a secret that should not have turned up again at the bottom of a bag of notes. He cannot possibly know what she does not know herself: whether he is the son of love-making on the floor (in this very room where the letter is in her hand) one last time with the returned soldier, or whether he is the son of his mother’s lover, Bennet.

He does know. Somehow he does know. She has an irrational certainty. It was always there, can’t be denied; he doesn’t only look like her, in the genes that formed him is the knowledge of his conception. If she has never known who fathered him, he does. The first cells of his existence encoded the information: he is the child of the childless first marriage, conceived after it was over on this bedroom floor in an hour that should be forgotten. The information was always there: when she and Ben took him into their bed for a cuddle, as a tiny child, and in the inner-focussed emergence from sleep his gaze would be fixed on her eyes; when, a grown man, a banker, he danced with her, each holding the other in their secrecy.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «None to Accompany Me»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «None to Accompany Me» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «None to Accompany Me» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.