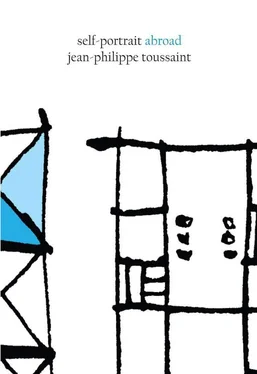

Jean-Philippe Toussaint

Self-Portrait Abroad

Every time I travel I feel a very slight feeling of dread at the moment of departure, a dread sometimes shaded with a soft shiver of elation. Because I know that any trip brings with it the possibility of death — or of sex (both highly improbable of course, yet not to be excluded altogether).

You arrive in Tokyo the way you arrive in Bastia, from the sky. The plane flies in a long arc above the bay and aligns with the runway to touch down. Seen from above, at four thousand feet, there isn’t much difference between the Pacific and the Mediterranean.

Chrisitan Pietrantoni, incidentally, a Corsican friend of Madeleine’s — I will call Madeleine Madeleine in these pages to help me get my bearings — promptly got in touch with me to arrange a meeting in a Tokyo café and fill me in on what had been happening back in the village. The very day after my arrival, hardly leaving me the time to unpack my bags, he called me up in my hotel room while, dressed in a white shirt and small blue cardigan of the sort worn by retired teachers (a New Year’s gift from my parents), I sat on the bed in my socks flipping through a sports magazine and awaiting the imminent arrival of a journalist who was coming to interview me. Seated at a round table right next to me in the room was Mr. Hirotani of the Shueisha Publishing House, who since the beginning of my stay had been alternating with Mrs. Funabiki as companion and confidante, guide and bodyguard, and who I perceived out of the corner of my eye in a perfect suit and tie, his face grave and attentive, busying himself arranging in a vase a bouquet of flowers I’d been given. He was grappling with five purple and white flowers (the Anderlecht colors, I’m not sure if it was intentional), whose position he altered incessantly to compose a harmonious bouquet, regularly starting over again from scratch, changing here the position of one flower, there the position of another, looking more, it seemed to me, like a thug from a film by Godard than a connoisseur of Japanese floral arrangement. And as I continued to observe him discreetly, lazily turning the pages of my magazine while voluptuously crossing and uncrossing my stockinged feet on the bedspread, the telephone rang out in the room. Dropping his flowers on the carpet, Mr. Hirotani dashed to the telephone in a single bound. Putting his arm over my head he seized the phone on the bedside table and gave a discreet, courteous pull on the cord which had inopportunely got twisted around my neck and shoulder. Strangling me for an instant while trying to get it untangled, he took the cord cautiously in both hands, passed it over my head and answered the telephone with an apologetic look. My head raised, I tried to guess who he could be talking with, someone from hotel reception or the publisher, perhaps the journalist we were waiting for from Yomiuri Shimbum . Standing there beside me he listened gravely, mechanically retying the knot of his tie. Yes , he said, yes. It’s for you , he said, handing me the receiver: Christian Pietrantoni.

I made a date with Christian Pietrantoni for two days later and, after a first missed meeting one night in a South American bar in Roppongi, he came to fetch me one morning at the hotel. Taking off our coats we walked side by side in Tokyo under the island sun before stopping at a modern, insipid, and impersonal café. Although it was pastis time we contented ourselves with a green tea, and, while young girls ate at the next tables in a cacophony of chopsticks and Japanese voices, Christian Pietrantoni, sitting across from me, perfectly indifferent to the surrounding atmosphere, filled me in on the latest news from the village. He told me what Nono and Nénette were up to, the Albertinis, the Antomarchis, what do I know. I wondered what source he had for all his information (perhaps he had correspondents in other Asian capitals?). Accompanying me back to the hotel he gave me what was no doubt one key to the mystery when he let on that he had a subscription to Corse-Matin . Before saying good-bye we promised to meet up again soon, in Ersa or Tokyo, London or Macinaggio, then shook hands vigorously the way Westerners do in front of hotel entrances.

I had strange experiences with my hands in Japan. I don’t know if it was because of the hotel I was staying at, the types of material the building had been constructed from — the fact, for example, that its doorknobs were mostly made of metal and not wood — or whether the cause of all these little irritations had more to do with my wool cardigan (a New Year’s gift from my parents)…nevertheless, each time I was about to take hold of a doorknob or press an elevator button, I got a shock of static electricity. But enough of personal matters.

We’d landed in Hong Kong a few minutes earlier, flying over the city at a ridiculously low altitude, thirty or so feet at most, the immense mass of the Boeing slamming down onto the runway after barely scraping over the rooftops and flying over a last shop-lined street where you could see men in white shirts, cigarettes in their mouths, crossing the road without paying the least attention to the insane spectacle that this gigantic airplane must have presented overhead, or else standing tranquilly on their doorsteps, arms crossed, taking in the fresh air of this bustling Hong Kong street where thousands of multicolored ideograms blinked continuously in the night. Not long beforehand, when the plane was still much higher in the sky and turning slowly in the air to commence its descent, the entire bay of Hong Kong had suddenly appeared through my window in a twinkling of luminous blue and white points, revealing farther off the presence of other urban concentrations, Macao or Kowloon, whose illuminated agglomerations shone out against a background of bluish mountains barely visible as shadowy profiles in the night. Meanwhile, on the surface of the water below us, among the silhouettes of the cruise ships and barges, cargo and container ships, floating casinos and nightclubs where you could dance the salsa or mambo-mambo under dotted strings of lamps, the navigation lights of thousands of solitary junks rocked slowly to and fro, dotting the bay like so many fireflies.

Seated on one of those anonymous plastic seats in an immense hall at Hong Kong International Airport, I looked at the dirty linoleum floor between my legs, thoughtful, my hands joined and my body inclined, a little lost and disoriented (I’d taken off from Osaka some five hours earlier and was headed for Frankfurt where I was due to land in twelve more hours). I didn’t know where I was and no longer really knew where I was going. I’d already had a similar feeling of the momentary loss of temporal and spatial landmarks a few days earlier in the plane that had taken me to Japan when, sitting drowsily in my seat, I suddenly became aware looking out the window that it was neither day nor night outside, but simultaneously day and night, and that to the right of the plane I could see the moon, shining in the sky in-line with the wing, as well as the sun, far out in front of us, which for the moment was still just a blurred pink and orange glow similar to the cottony contours of a Rothko, lighting up the horizon of this immense sky divided evenly into day and night, into Europe and Asia. The silent cabin of my sleepy seven-forty-seven was still convinced of its being night, however, as it flew in perfect stillness toward Tokyo to the hushed droning of its motors, my watch showing one o’clock in the morning, the other passengers dozing around me in the feeble light, the small plastic blinds on the windows carefully lowered, to say nothing of my own fatigue after seven or eight hours of flight, my eyes heavy and closing softly, yes, everything seemed to indicate that it was night — apart from one important detail: it was now broad daylight outside.

Читать дальше