On Thursday they took things easier: they watched cartoons all morning before going out to play. Then they opened up the igloo, whose doorway had become buried during the night. They tracked, without much luck, the paw prints of some hungry raccoon that had been foraging in the yard for food. After lunch they noticed that it had stopped snowing and the sun was just peeking through, so they went to go sledding again. Lacking the energy of the day before, they soon returned to the house, where they watched cartoons the rest of the afternoon. The girls were delighted to have sausages for dinner a second time, but he wasn’t so thrilled: he was getting fed up with his own lousy cooking. They didn’t hear the roar of a snowplow that day either.

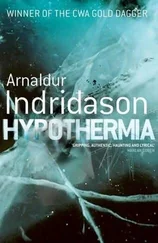

On Friday he spent the morning digging out the car, possessed by the hope that they would soon be clearing the street. In the afternoon they dragged the sleds to the hill, but after sliding down the first time they noticed how difficult it was to climb back up because the snow had turned to a sheet of ice. They made snow angels on the park’s basketball court, then almost got hypothermia pretending to be Eskimos living in the igloo. They watched all the cartoons on TV. For dinner, he thawed out some hamburgers.

They were out of juice, but still had enough things for breakfast, lunch, and dinner through Sunday. If the snowplow didn’t come by then to clear their street, on Monday he and the two girls were going to have to make a big supermarket run on the bus. The very thought of such a trip seemed nightmarish: the emergency route used by public transit was four blocks away, a distance he would not normally have minded walking, but the idea of hauling the shopping bags through such deep snow struck him as actually frightening.

Sunday morning was, frankly, abysmal. After lunch — he was washing the dishes from their lunch of tuna and saltines — his older daughter realized that they had not taken any pictures of the igloo to show their mother, so they got out the camera only to discover that it had no film. Let’s go buy some, he told them, with the joy of one surprised to find himself set free. He dressed them as if they were going on an expedition to the North Pole and they walked to the Metro station; even though it was a little bit farther than the bus stop, it took them right to the shopping mall.

Life there seemed to be following its normal routine. They spent the afternoon buying snacks, thankful for the novelty of the scene. At some point they sat down to have an ice cream and he realized that he had not seen a black person since Tuesday, nor any Arabs, Hindus, Asians, or Mexicans: only his own neighbors, whiter than ever for the wintertime lack of sunshine. The folksy look of the gangbangers at the next table sporting their NFL jerseys and clownish sneakers was comforting to him. As the afternoon wore on, the girls proposed getting a video camera to tape a report. So they went to buy it. Tomorrow, he told them as he was paying, we’re going skating at the rink, if school’s still out, and we’ll do our shooting then.

He didn’t like watching himself on the screen — his face looked wider and flatter than it did in the mirror and he couldn’t even recognize his profile — so he rewound the tape until he found a part that he had shot himself. He located it right away and then kept rewinding. He saw the girls walking backward into the door of the skating rink at the sculpture garden, the confusion of the people skating backward and the girls among them, holding hands, cracking up laughing and picking themselves up from the ice every now and then. He saw them taking off their skates and putting on their sneakers in reverse order, leaving backward through the entry and saying hello to the camera. Then followed random sequences of the white capital.

The shots stopped their dizzying advance at an unusual moment that he had completely forgotten: in the middle of one frame there was a pickup truck perched whimsically on a snowdrift about three feet tall, high enough so that the truck wouldn’t have had enough traction to drive over it. He took his finger off the rewind button and listened to his own voice discussing with the girls the impossibility of what they were seeing. He heard himself say that it was so strange it seemed as if the truck had been lowered from a helicopter.

By that time he had spent several days meditating on the spectacle of the snow and the purification ritual it performs in a society that believes itself born to rule by virtue of race. With the snow just starting to fall, he had glimpsed in the distance, from a room on the fifth floor of the Washington Hotel, the snowy landscape of Pennsylvania Avenue, ostentatiously white by nature: the White House and the Treasury building in the foreground, the narrow, foreshortened canyon between the museums along the Mall, Congress at the far end — all marble. Seen from above, it had occurred to him, the city had the quality of a poisoned dessert. What? she asked — they were leaning on the inside sill of the closed window, their hips, shoulders, arms touching, nothing in between. He said that for the rest of the East Coast it was just a big blizzard, but in the capital it was Mother Nature’s affirmation of Manifest Destiny. She laughed and asked him when he’d stopped being pro-Yankee. Since you started working at the World Bank? Since I became a gringo, he replied. She added that he was imagining things. Why had he bothered to become a citizen if he was just going to complain about it? The only thing wrong with you, she concluded, is that you work too much. Just like my husband. Then she sent him home: You’ve got to go; the girls will start to worry.

Now down in the Metro, nearly deserted, he found a little folded paper inside his eyeglass case. It was a note written on a tiny white circular sheet, like a communion host, perhaps slightly larger. He unfolded it, knowing that it was a message from her: she always left him notes written on her own delicate stationery. He read the words, printed in a Catholic schoolgirl’s writing: Tonight I’ll step out on the balcony and open my mouth, each snowflake a drop of your semen. He considered it for a moment, folded it back up and ate it: he usually disposed of the evidence immediately, even when, as in the subway car, there was no trash can.

By five o’clock in the afternoon it was completely dark and he was already back home — his house felt increasingly like a shirt that was out of fashion. Between the girls’ excitement and the TV news announcement that buses throughout the county would stop running at nine o’clock, the Argentine babysitter was hysterical. He sent her home with a generous tip.

He played the video to see if he could recognize in the shots taken at the skating rink the men they would later identify as the owners of the pickup stuck on the snowdrift. The screen was too small and the throng of skaters too thick for him to spot them. The one thing he was sure of was that they had filmed the moment when they freed the truck from the pile of snow, so he pressed the fast forward button.

The owners of the truck had caught their attention before they even knew who they were. At the shopping mall they would have passed by unnoticed, but at the skating rink filled with white people coursing over the white ice among the white monuments, they stood out scandalously. They were four heavyset guys who looked very much alike and called each other güey —“dude”—something only a Mexican would say.

When the girls got tired, long before the two-hour skate rental was up, actually a little too quickly, considering the long ride on public transit from the suburbs, he took them to have some hot chocolate at the cafeteria across from the skating rink. They waited until they warmed up again before heading back to the Metro. On their way there, they saw the fat guys again, walking along like four giant penguins in their high-visibility jackets.

Читать дальше