Campesinos along the road gave the V for victory sign, shouting “Mau Mau! Mau Mau!” a term that had recently become popular, an allusion to Kenyans fighting to drive out colonial British rule — rebels who, like the Cubans, were shaggy and unkempt. They waved back from the jeeps as they rolled down the rutted road, La Mazière a Mau Mau, too, thanks to a shortage of razors in the mountains.

Some of the younger men fired their guns into the air. You waste those bullets now, La Mazière thought, but you’ll want them later, for the cascade of reprisals.

They descended the foothills of the Sierra Cristal and reached Birán in the early afternoon, stopping for a brief visit at the Castro hacienda. Señora Castro appeared on the porch in a black lace mantilla and cat-eye glasses and clutched Fidel like a lover she had believed she’d lost forever. La Mazière sat in the shade of a grove of giant algarroba trees with Hector and Valerio, laughing as a younger rebel from their troop entertained them by chasing a nervous rooster across the lawn. Several maids and a butler came out of the house, the butler outfitted like the maître d’ at Maxim’s, in a crisp white jacket and bow tie, white gloves, a starched tea towel folded perfectly over his arm. The maids and the butler in his formal attire served cane juice from frosted-glass pitchers, wonderfully cool and sweet. La Mazière and the others sipped their cane juice, waiting for Fidel and his mother to finish their brief and Oedipal embrace.

The procession continued toward Preston, for a local-boys-make-good celebration. They detoured through the cane cutters’ slum on the outskirts of the town, a miserable-looking place with an open sewer running along a dense collection of primitive palm-leaf huts, hundreds and hundreds of them, possibly thousands. People flooded out of the huts and surrounded them. Women cried and hugged husbands who’d been away fighting in the mountains. Barefoot children and toddlers in raggy diapers climbed over the tanks, boys and girls putting on the armbands that rebels flung from the jeeps. Someone even fitted one around a newborn baby’s head, M-26 in red and black banding its young and tender skull.

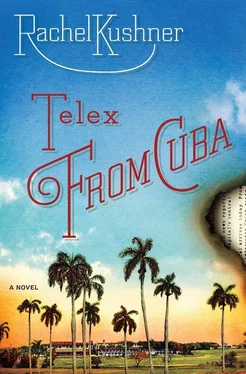

They parked the vehicles in the center of town, in the midst of what seemed to La Mazière a rather impressive colonial enclave. On their way to Preston, they had circled through Nicaro, the other now-empty American community in the region. It looked like a caricature of middle-class values, a town through which a toy train snakes, absurdly tidy, though its white houses were stained a faint pink. At first La Mazière suspected it might have been due to the tint of his eyeglasses, but then he realized that the entire town was coated in a fine reddish grit. Beyond the town, a workers’ slum. But the Nicaro slum, unlike Preston’s, had been burned to the ground, a remnant of the Rural Guard’s campaign of terror, which had worked against them and made every Cuban in the region a rebel sympathizer.

Preston was far more obvious and immodest than Nicaro in its wealth. The homes were enormous, with wraparound porches shuttered in varnished louvers, plantation estates that he guessed were modeled on those in the American South. The gardens of each enormous home were showcases of tropical foliage, the teeming verdure of Oriente crimped and strangled into picturesque mise-en-scène. Beyond one of the avenues a flawless green carpet rolled into the distance: a golf course, and adjacent to the golf course, polo fields.

Fidel gave a speech on the main plaza, more angered and moving and animated than any of the speeches the commander had delivered over Radio Rebelde, to which La Mazière’s unit had listened or half listened while eating their nightly mess-tin ration of rice, bananas, or horse meat.

The three men who remained from the town’s Rural Guard station stood uncomfortably to the right of Castro’s retinue while the commander spoke. As surprised as anyone that Batista had fled, they were now abandoned to their fate. Castro had offered them amnesty if they gave up their guns, and what choice did they have? They stood, abject, stripped of their weapons, feigning enthusiasm for the transfer of power, trapped in an awkward fact of civil war: that the enemies often have no choice but to remain, either to be integrated, punished, or disposed of. La Mazière himself had avoided such a fate by enlisting in the Waffen, departing Paris as Germans and collaborators lined up to board transport vehicles fleeing east, to Sigmaringen. As he was driving out of town he’d seen the author Céline waiting in one of those lines, hurriedly stuffing his cat into a cardboard carrier.

They were gathered in the heart of imperialismo, Castro announced to the assembled rebels. Castro pointed to a set of offices, three-story buildings painted a mustard yellow. “La United,” he said, aiming an accusatory finger at the buildings, as if the name alone were an indictment.

This town, Castro said, was the location of his own childhood dreams, this very place where they were gathered. Off-limits and American, it was the site where his imagination had been ignited, and roamed. Freely, he said, but in the freedom of dreams. The town of Preston was make-believe in its distance from his life just a few kilometers away, in Birán, make-believe in its luminosity, its impossibility. But real in its control, its ownership of everything and everyone.

“Off-limits and American,” he repeated. “But of course, as many of you know, we Cubans were invited to cut the cane.”

There was laughter.

“Invited to lose an arm feeding the crushers at the mill. Invited, most graciously, to be fleeced by the company store, whose prices were unspeakable exploitation, invited into a modern and more efficient version of slave labor. But you and I were not allowed beyond those gates over there,” he pointed, “where the managers lived. ‘La Avenida,’ with, take note, the definite article. The avenue, but, of course, only for some. You could not walk down it. You were not allowed to swim in the company pool, go to the company club, use the company’s beaches. You could not fish in their bay, Saetía, or go to school with their children, or date their daughters, or God forbid, should you get sick, be treated at their hospital. You could not own your home, which you yourself had built, own your own plot of land, which you worked with your own shovel, your pick, your hoe.”

He said that he’d spent his boyhood gazing from beyond the scrolled iron gates that enclosed La Avenida, gazing, he said, at a mirage overlaid with black arabesques, the wrought-iron bars of a fence through which he’d looked. A small boy, wanting only to glimpse a magical place.

That was all he’d wanted as a young boy, and it was all he’d been given.

“There is another man,” Castro said, “whose destiny was shaped by La United: Fulgencio Batista.”

People booed and hissed.

“Let me make myself clear. Batista and I,” Castro said, “are opposites. We both gazed through the fence, he in Banes, myself here. I grew up to hate imperialists. He grew up to love them, and learned to ingratiate himself on their terms. Became president and accepted their bribes, no less humiliated than a cane cutter! We are opposites. My father was a landowner. Batista’s father was a guajiro who squatted on company property. Batista was born in a dirt shack, with nothing, like the men who worked my father’s land. Born in a dirt shack. His destiny was to humiliate himself for the American landowner. Perhaps a man cannot change his destiny. Perhaps he has no choice. My own destiny was to evict the American landowner—”

There was cheering and applause and shouting.

“Viva Castro!”

“Viva La Revolución!”

The Rural Guardsmen standing at the front smiled uncomfortably. One managed a limp clap of his hands amid the ocean of applause.

Читать дальше