Rachel Kushner

Telex From Cuba

I would like to thank Susan Golomb and Nan Graham for their unerring

editorial guidance, and Fred and Mary Lou Drosten for leaving

such a rich legacy and living remarkable lives.

This book is for Jason Smith.

All is order there, and elegance,

pleasure, peace, and opulence.

—“Invitation to the Voyage”

Everly Lederer, January 1952

There it was on the globe, a dashed line of darker blue on the lighter blue Atlantic. Words in faint italic script: Tropic of Cancer . The adults told her to stop asking what it was, as if the dull reply they gave would satisfy: “A latitude, in this case twenty-three and a half degrees.” She pictured daisy chains of seaweed stretching across the water toward a distant horizon. On the globe were different shades of blue wrapping around the continents in layers. But how could there be geographical zones in the sea, which belongs to no country? Divisions on a surface that is indifferent to rain, to borders, that can hold no object in place? She’d seen an old globe that had one ocean wrapping the Earth, called Ocean. In place of the North Pole was a region marked “Heaven.” In place of the South Pole, “Hell.”

She selected the color black from a list of topics and wrote her book report, despite feeling that reducing Treasure Island to various things colored black was unfaithful to the story, which was not about black, but perhaps how boys need fathers, and how sometimes children are more clever than adults and not prone to the same vices. The Jolly Roger was black, and there was Black Dog, who showed up mysteriously at the Admiral Benbow, demanding rum. There were black nights on the deserted island, creeping around in shadows amid yet more blackness: the black of danger. Also, the “black spots” that pirates handed out — a sort of threat. A death sentence, really. “Who tipped me the black spot?” asked Silver. This death sentence, a stain of wood ash on a leaf of paper. The leaf, torn from a Bible, which now had a hole cut into Revelation. And holes are black as well.

She’d read about Sargasso, a nomadic seaweed city, and hoped they would encounter some. Other things floated on the ocean as well: jetsam, which is what sailors toss overboard to lighten their load, and flotsam, things caught and pushed out to sea, such as coconuts, which rolled up on the shores of Europe in a time before anyone knew what lay to the west. Maybe coconuts still washed up, but they weren’t eerie and enchanting now that you could buy one at the store. In that earlier time, people displayed them as exotic charms. Or cut them open. A strange white fluid poured out, greasy and foul-smelling. Not poisonous, just spoiled from such a long and difficult journey, a fruit thousands of miles from its home under the green fronds of a palm tree.

To get from green to red is easy: they are twins. Thin membranes, like retinae, attached at their backing. Her father saw red as green, and green as red. A permanent condition, he assured her. And there was a red grass native to the Antilles from which you could make green dye.

Now picture red velvet drapes.

Part them.

Beyond is a room with perfect acoustics. In it, a gleaming black piano. She can see her face in its surface, like she’s leaning over a shallow pan of water. She sits down to play — Chopin, a prelude for saying good-byes, for dreaming in a minor key.

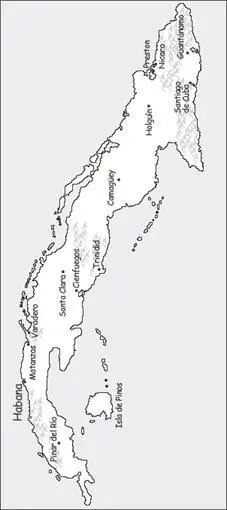

Spin the globe slowly, once, and return to where the dashed blue line skims above the island of Cuba.

She will cross the Tropic of Cancer and begin her new life.

January 1958

It was the first thing I saw when I opened my eyes that morning. An orange rectangle, the color of hot lava, hovering on the wall of my bedroom. It was from the light, which was streaming through the window in a dusty ray, playing on the wall like a slow and quiet movie. Just this strange, orange light. I was sure that at any moment it would vanish, like when a rainbow appears and immediately starts to fade, and you look where you saw it moments before and it’s gone, just the faintest color, and even that faint color you might be imagining from the memory of what you just saw.

I went to the window and looked out. The sky was a hazy violet, like the color of the delicate skin under Mother’s eyes, half circles that went dark when she was tired. The sun was a blurred, dark red orb. You could look directly at it through the haze, like a jewel under layers of tissue. I figured we were in for some kind of curious weather. In eastern Cuba, there were mornings I’d wake up and sense immediately that the weather had radically turned. I could see the bay from my window, and if a tropical storm was approaching, the sunrise would spread ribbons of light into the dense clouds piling up on the water’s horizon, turning them rose-colored like they were glowing from inside. I loved the feeling of waking up to some drastic change, knowing that when I went downstairs the servants would be rushing around, taking the patio furniture inside and nailing boards over the windows, the air outside warm and gusting, the first giant wave surging in a glassy, green wall and drenching the embankment just beyond our garden. If a storm had already approached, I’d wake up to rain pouring down over the house, my room so dark I had to turn on the bedside lamp just to read the clock. Change was exciting to me, and when I woke up that morning and saw a rectangle of orange light, bright as embers, on my bedroom wall, it seemed like something special was about to happen.

It was early, and Mother and Daddy were still asleep. My brother, Del, had been gone for three weeks at that point, ever since we’d returned from our Christmas vacation in Havana. Daddy didn’t talk about it openly, but I knew Del was up in the mountains with Raúl’s column. I’d never been much for the pool hall in Mayarí, but I started hanging around down there after he disappeared. In Preston it was difficult to get information about the rebels. The Cubans all knew what was going on, but they kept quiet around Americans. The company was putting a lot of pressure on workers to stay away from anyone involved with the rebels. Who’s going to talk to the boss’s thirteen-year-old son? Down in Mayarí, people got drunk and opened their mouths. The week before, an old campesino grabbed me by the shoulder. He put his face up to mine, so close I could smell his rummy breath. He said something about Del. He said he was still young, but that he would be one of the great ones. A liberator of the people. Like Bolívar.

I could hear Annie making breakfast, opening and shutting drawers. I put on my slippers and went downstairs. It was so dark in the kitchen I could barely see. Annie had latched all the windows and closed the jalousies. I asked why she didn’t open the shutters or put on a light.

Servants have their funny ways — superstitions — and you never know what they’re up to. Annie didn’t like to go out at dusk. If Mother insisted she run some errand, Annie put a scarf over her mouth. She said evil spirits tried to fly into women’s mouths at dusk. Annie and our laundress, Darcina, both listened to this cockeyed faith healer Clavelito on radio CMQ. Darcina sometimes cried at night. She said she missed sleeping in a bed with her children. Mother bought her a portable to keep her company and ended up buying one for Annie as well, just to be fair. Mother was big on fairness. Clavelito told folks to set a glass of water on top of the radio, something about his voice blessing the water, and Annie and Darcina both did.

Читать дальше