A human trapped inside a monkey trapped inside a cage. But when she tried to put him down, he screeched like a vicious animal.

IN HAVANA AS IN PARIS…

MADAME MASIGLI SHOPS AT JEAN PATOU.

We’re proud to offer Her Excellency Masigli’s favorite scent, COLONY, celebrating the tropics since 1938. Available in perfume, cologne water, talcum, lotion, and soap.

Visit our exclusive showroom, Prado 157 between Colón and Refugio, or purchase by mail order through El Encanto.

Blythe Carrington closed the catalog and sat powdering her complexion, perspiring through the powder, then powdering again. It was useless. Sweat and humidity were turning her makeup to paste. She gave up and downed the last of her lukewarm stinger.

The temperature hadn’t dipped under eighty-five degrees since she and Mr. Carrington and their twin daughters, Val and Pamela, arrived in Nicaro four weeks ago. Unlike their neighbors, the Lederers on one side and the Billings on the other, who showed up with wardrobes of synthetic cloth that not only transformed body odor to an inorganic stench but also melted after one day in the climate of eastern Cuba, Blythe Carrington wore cotton and hadn’t been a bit surprised to encounter damp tropical heat. She’d spent her adult life suspended in it. But tonight the air was heavy and windless as the air in a shut closet, though instead of mothballs she smelled oxide dust. The plant had begun production, the managers too impatient to wait for the new chimney scrubbers to arrive from the States. And so the town was coated in oxide dust — reddish, and blending grittily with the humidity. To make matters worse, Tip Carrington had used up the last of the cube ice, and so lukewarm stingers.

She was already slightly drunk, what she thought of as twilight drunk: a special moment when she was still sober enough to notice she was drunk, caring more about certain things and less about others, her vision blurring around the edges like a camera with a twinkle filter on its lens. And she was already irritated with her husband, who’d dressed, greased his hair, and patted on cologne with the attentive optimism of a horny bachelor.

As she went to fix another drink, Val and Pamela came into the living room.

“Mom,” Val said, “I think it’s only fair to let us go to the party. There aren’t any kids our age in town, so we should be promoted to adult things.”

Blythe Carrington replied that no one else was bringing teenagers, that it was a meet-and-greet expressly for employees and their wives. Pamela, more hotheaded than her sister, protested that no one was bringing teenagers because there weren’t any teenagers. She said they’d been carted off to live in this muddy two-bit nowhere and get followed around by a weird eight-year-old like Everly Lederer. Pamela marched down the hall and slammed a door, then opened it so she could slam it again. A nasty little habit she’d learned from her father. When Tip Carrington had successfully broken every door in their house in Bolivia, he’d resorted to slamming kitchen cabinets, and had broken all of those as well. Blythe Carrington knew about anger, but she didn’t bother with doors. Fix yourself another room-temperature stinger. That was Blythe Carrington’s answer to everything.

“I hate this place!” Pamela yelled. “It’s ugly and we have to live under a disgusting factory. My shoes are all ruined because these idiotic people haven’t paved our road.”

Why Pamela had developed this irrational homesickness for Bolivia was beyond Blythe Carrington. Another corrupt hellhole where her husband had screwed the maid, the laundress, his secretary, and his assistant’s secretary. Where they’d lived a life of tenuous appearances and outright lies. And where her husband’s engineering job at the silver mine had lasted only so long as the hostile locals remained firmly under the company’s shit hammer. Which wasn’t long. When the revolution began, they ran for their lives. Her husband’s employees — the same miners who’d brought gifts, little hand-woven native things, to the house after Tip Carrington successfully negotiated a better ration card system for them — were suddenly the angry mob lobbing medium- and large-sized rocks at their car as they fled to the port in Sulaco. Even the wives had flung rocks.

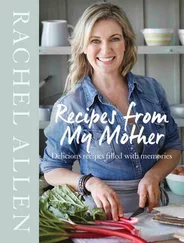

Blythe Carrington placated Val and Pamela by telling them they could order whatever they wanted from the El Encanto catalog on her dressing table. Val retrieved it, happy to shop, and to shop expensively.

“Here, Pamela,” Val said. “Colony perfume by Jean Patou. From France .”

“I love Colony perfume,” Pamela said, folding the page corner to mark it. “And it’s only forty-five dollars.”

When the jeep arrived to take the Carringtons to the party the moon had just appeared, rose-colored and hanging low and giant like a ripe mango. Probably the nickel dust, giving it that hue. Mist was settling in the air, and Blythe Carrington felt relieved to be outside, under that moon and free, for a moment, of her own petty irritations. They were going to a party, and the party might actually be fun. Over the past three weeks people had been arriving in dribbles, moving in along the manager’s row. She’d met a few of the wives at the ice factory and the club, and gotten a vague sense of who might make tolerable company, who not. But tonight was the first official gathering, and everyone would be there.

The party host was this mysterious Gonzalez character whom people had been gossiping about since the Carringtons arrived. The “Cuban millionaire” who’d finagled his way into the nickel mining operation. They were all going up to his hunting lodge on the Cabonico River. She wasn’t sure what to expect, and that alone was reason for hope.

The jeep fetched Mr. and Mrs. Lederer, and they made their way up the steep, rutted, and narrow road to Lito Gonzalez’s remote lodge. Branches xylophoned down the sides of the jeep as it forced its way through the foliage that strangled the road’s throat. They ducked under a fig tree, and giant water-filled leaves upturned like ladles, raining into the jeep. Figs plopped on the hood like soft leather pouches.

The river rushed loudly as they pulled up in front of a three-story house that looked like it had been slapped together with driftwood and rusty nails.

“My God,” Blythe Carrington said, “a polite person would call this ‘rustic.’ I call it a dump.”

The house was on stilts, pitched over the river, and the entire structure seemed to be listing to one side. Ivy and lianas coiled up and around the eaves of its sagging roof. More vines smothered the exterior and hung down from the power lines in tangled masses, like drain clogs of human hair.

Lito Gonzalez greeted the four of them as they entered the dimly lit foyer, pronouncing their names slowly, carefully. He was wearing pressed gabardine — the jacket with an excess of shoulder padding, the pants with an excess of pleats girdling his large middle.

New management people and their wives, some of whom Mrs. Lederer had met, others she’d only seen in town, were crowded around the bar, where white-jacketed Negroes were pouring drinks from a cart of gleaming liquor bottles. Mrs. Lederer tried not to seem too eager as she waited her turn to get a drink. She felt slightly frantic, like this was a department store white sale and the best linens would be gone before you knew it. The girls were at home in Nicaro, where they would be watched over by the new houseboy, and she was planning on getting good and drunk.

“Never get tight at a company affair,” Fortune magazine advised in the issue devoted to management social mores. Marjorie Lederer had read it cover to cover and taken notes. But after only three weeks in Cuba she’d come to understand that management people drank. And did they ever.

Читать дальше