They stopped at an Esso station. Marjorie Lederer handed out sandwiches she’d made in their hotel room that morning in Santa Clara, having found a store that sold American things, white bread and mustard to go with the ham.

“Does ham come from Hamburg?” Everly asked.

No one replied.

“Will we be taking a tram?” She knew they weren’t taking a tram. She liked the word. It looked, on paper, like it should have something on the end of it. A b, maybe. Tramb.

She sensed there was a new policy in the car, of the adults not answering her questions. If they were going to ignore her, she would ask whatever she felt like asking.

“Is it ‘morbid’ if I think about other people dying, or only myself?”

“If a person had a face like Scribbles, would she be a brand-new person every time her face got erased and redrawn? Or would she only be tricking people into thinking she was new?”

Duffy was putting eyelashes on Scribbles, swoopy and outsized like the legs of a tarantula. Even after you were dead, Everly thought, you were trapped in your own face. That is, if anyone had taken photographs of you, which was likely. What if she could change her face and not be permanently trapped in the one she was born with? Or just erase her features? When Scribbles’s face was blank, you really could not tell what she was thinking. Surely there were advantages to being able to make your face occasionally blank, erase it and go around like that.

As they were getting gasoline, a man approached the car carrying a basket covered with cloths.

“Americanos! Vende Puffs!” he called. “Hot puffs! Carne o guayaba! Meat or jam!”

George Lederer said no gracias.

“Puffs! Hot puffs!”

A Cuban father waiting at the other gasoline pump bought some and handed them to his children in the backseat.

“I want a hot puff,” Everly said. “A meat one.”

She was given a ham sandwich, which seemed plain and ordinary and did not belong. A familiar thing you didn’t want to see at a gas station somewhere in Cuba, electric green all around. You wanted to eat a puff, whatever it was. A hot puff. Meat or jam, they both sounded good.

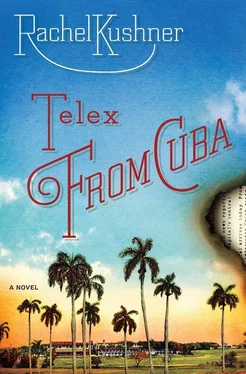

Her father drove and her mother navigated. There were tall palm trees along the road, and in the folds between the green hills, clusters of funny little shacks. They looked like yellow jacket hives, molded clumps of mud and leaves. Everly asked if people lived in them. Her father said they did, that they were native huts. That’s how the Cubans live, he said, in huts.

There were fewer huts, and mostly sugarcane fields, when they had to stop because a river was rushing over the road.

Her father turned off the car, and everyone sat quietly, waiting as he tried to figure out what they should do. They heard animal hooves, a Cuban family in a horse-drawn wagon. The horse stalled when he reached the water, but the driver whipped him to keep going. The horse stepped slowly into the water, deeper and deeper, dragging the wagon after it, until the wheels were three-quarters submerged.

Two men were working on the side of the road, hitting a fence post with a large rock. Each wore the straw hats that all the men, once they’d left Havana, seemed to wear. Her father walked over to them. They listened as he communicated with hand gestures and broken sentences.

He said “Auto,” and pointed at the car.

He said “Water,” making a wavelike hand motion. “Is it possible to cross?”

One of them nodded. “Sí, sí.”

Her father smiled cheerfully, as he and one of the Cubans walked toward the car. He announced that the nice man had offered to guide it across for them.

“George, this person cannot drive our car,” Marjorie Lederer said. “I won’t allow it.”

George Lederer was in charge of everything, but he had to be in charge exactly her mother’s way.

“This man,” her mother said, “cannot even speak English.”

The man took off his hat, wiped his forehead on his shirtsleeve, and smiled politely at Marjorie Lederer.

“He doesn’t even understand me! And this is the person you’re giving our car keys to?”

“Dear, these men are locals,” George Lederer said, “and I think it might be worth—”

“It might be worth what ?”

“Letting them help us, dear.”

“Fine.” Marjorie Lederer opened her door and announced to the girls that their father was figuring this one out on his own while she sat in the bar just up the road. Anyone who wanted to come could come. Everly and her sisters got out and followed her.

George Lederer was always talking to strangers, which irritated and embarrassed Everly’s mother. Everly could tell when other people didn’t feel like chatting. Her father kept on anyway, talking to strangers in line at the bank or the bakery, telling them his name, what type of work he did, what he was buying or sending or depositing. “Sending this to Cuba,” he’d said to a woman behind him in line at the Oak Ridge post office, pointing to the address on the package he was carrying. “The whole family is moving there.” At the Oak Ridge bakery, he told stories to the people in line. “Grandma Lederer was a baker — right, Everly? She lives in St. Louis. She’s retired now, but she ran a bakery downtown. I worked there as a child. She and my father made cheesecakes in flat, rectangular pans that were too big to fit on the shelves. They put the cakes on the floor to cool. One night, when I was very small, probably six years old, I got out of bed to get a drink of water. It was dark and I didn’t see the cake on the floor and I stepped in it.” He could go on and on this way. It was embarrassing, but when her mother scolded her father, it made Everly want to try not to be embarrassed by him.

The bar was open-air, covered by a palm-leaf roof. Everly’s mother ordered drinks, and the bartender lined up four ice-filled glasses, poured lemonade into them, and trickled red syrup over. It sifted down among the cubes in the glasses like a red dye. As they sipped their red lemonade, rain began to patter on the bar’s thatched roof, making a gentle, creaking sound like water hitting a wicker basket.

The man spoke some English, and he asked her mother where they were from and where they were going.

“You arrive in Cuba,” he said, “just in time for el golpe.”

Her mother asked what he meant.

“The change in the government, señora. A week ago. It was, how you say, con mucha fuerza. President Prio, he is no more presidente. He’s left to Miami, in un hotel lindo. Batista, el dictador, el general, he is presidente now. But with no vote. You did not hear?”

Her mother said no, no one had mentioned it in Havana. Had it been announced?

Yes, of course, he said, but everything was back to normal now. “For one whole day the radio station plays only music. The next day, they make the announcement. But maybe it was not in the American papers.”

Everly’s mother said it might have been, but she hadn’t had time to read a newspaper since they’d arrived. They’d left Havana immediately and had been on the road for the past few days, navigating maps and trying to get three children and twenty-one suitcases and a Studebaker all the way to Nicaro.

“And hams,” Duffy said. “We have seven hams!”

“Eight,” Everly said.

“We have eight hams!”

They had turned around and were taking another route on account of the washed-out road. To Preston, the United Fruit town across the channel, where a boat could take them to Nicaro.

“There was a golpe!” Duffy said.

“What’s a golpe?” George Lederer asked.

“I was getting to that,” their mother said, explaining that it was something the bartender mentioned. Some sort of major Cuban political event had occurred, and the old president had gone to Miami and was now apparently staying at a place called the Hotel Lindo, which was probably a heck of a lot nicer than the fleabag where the Lederers had stayed. The way the bartender had explained it, it hadn’t made much sense. Something about them playing only music on the radio station, and now everything was back to normal. But what if there was trouble?

Читать дальше