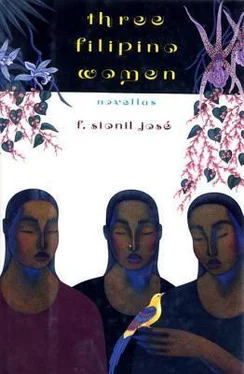

Francisco Jose - Three Filipino Women

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Francisco Jose - Three Filipino Women» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, ISBN: 2013, Издательство: Random House Publishing Group, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Three Filipino Women

- Автор:

- Издательство:Random House Publishing Group

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:978-0-307-83028-9

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Three Filipino Women: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Three Filipino Women»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

and

-examine the Philippine experience through the lives of three female characters, a prostitute, a student activist, and a politician.

Three Filipino Women — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Three Filipino Women», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“I have had many nasty experiences,” she said. “I don’t want them repeated.”

“I promise not to embarrass you.”

“I know that. But in the future, I am sure to meet these men again and there will be phony explanations to make.”

“I am not ashamed to be seen with you,” I said and meant it.

She pinched my arm. We were now on the highway to Calamba, bright and wide and hot. “I am sorry,” I said. “This ten-year-old Mercedes is not air-conditioned. I am not rich and martial law has been very unkind to me.”

“You need not apologize,” she said. “Just don’t take me to those ritzy places where there are many people. I am ill at ease there. I would rather go out at night, with no one seeing me, knowing me. I am tired having to look down, always avoiding the eyes of people.”

It all came back, the darkness being kind, hiding as it does almost everyone. I never knew and perhaps will never know what got her started in Camarin. But I do know that if money was the reason for her having started, it was not valid now as the cause for her return. “I am disturbed but glad because I can see you again. Why did you go back, Ermi? I thought that with your success with the Great Leader, the house in Forbes Park …”

“Are you going to give me a sermon again?”

“You are too old for that and I am too tired to give one. Besides, who am I to make judgments?”

“But you don’t approve of my going back, I know. Well, no one forced me in the beginning. And no one forced me to return, if that is what you want to know. I did it by myself.”

I told her that relationships in Camarin had a certain attraction, a magnetic pull to those who were there. Friendships, very strong bonds at that, were created. Her return was certainly welcomed by the girls there for it confirmed, it justified them.

“You are right,” she said. “But it was still my decision and I am answerable to no one but myself.”

The old highway was clogged with traffic and in the midday heat, she looked fatigued. I was relieved when we reached Calamba and parked in the acacia-shaded yard of the church where we went before visiting the old Rizal house. I told her about the ilustrados and Rizal’s Sisa and her two sons. The old house, how it was designed and maintained, fascinated her. She marveled at the number of fruit trees in the yard. She was interested in house-plants and on the way back, we stopped on the highway and I bought her a potted palmetto which I placed in the back of the car.

It was almost four in the afternoon and still hot. “I can drop you off in Cubao where you can get a taxi,” I said. “I know you don’t want me to bring you to your gate.”

She was quiet again for a time. We were now in Cubao and I turned to the right, to the Farmers Market parking area.

“You can take me home,” she said. “But promise not to get out of the car when we get there.”

Her house was in a small side street. It had high walls and a black, iron gate with a lock. She had a key and in a while, a boy came out and took the plant. I caught a glimpse of her bungalow and its yard green with plants.

“When will I see you again?”

“Next Sunday, late in the afternoon, if you are free,” she said. “I want to see Fort Santiago.”

I returned to Mabini convinced that I could not now free myself of her. Now, I wanted a definition of love not circumscribed by the sexual act for it had become mundane, a commerce bereft of those nuances for which a man would commit murder or suicide. Copulation was no longer an expression of love. While it was not sordid, it had become a measure of one’s wealth. The more I needed it, the more I had to pay. With Ermi, how then should I express myself? There are, of course, more profound ways of saying it, the immersion of the self in compassion. Love which is true after all demands no rewards, no favors. How easily I understood now that it is better to give than to receive.

But what could I give her? It was money she wanted most, which led her to Camarin and that commodity was not now easily available to me.

I took her to the old fort that Sunday evening shortly after nightfall. The walls were bathed with light and in the expanse before the entrance were people enjoying the cool night air. Some excavation was being done where the old moat was and they had dug up World War II relics, helmets of Japanese soldiers, bones. The Rizal cell was closed so we meandered to the top of the fort where I showed her the section of the Pasig where the galleons used to set sail for Acapulco. I pointed out the old Parian across the river and close by, the landmarks of Spanish sovereignty, the Manila Cathedral, the Archbishop’s Palace, the Ayuntamiento —where these used to stand. Then we went down the broad stone steps to where this solitary cross stands, a marker for the hundreds of Filipinos who were killed by the Japanese in the fort. She read the inscription intently and for a time, seemed engrossed in her own thoughts, then she asked, “Were the Japanese really all that bad during the war?”

Her question startled me. I had thought all along that Japanese brutality in World War II was taken for granted. But she was not old enough to have known the Occupation so I told her how it was, my own experiences, the campaign against Yamashita. Quickly, it came hurtling back, those iron cold, rainy nights in the mountains beyond Kiangan, the ribbons of mist that clung to the floor of the valleys in the mornings, and the Japanese — cornered, starved, demoralized — but still fighting viciously where we found them.

It was now thirty years after Yamashita had surrendered but the Japanese never really lost that war. They are back in full force, with their transistors, their lusts. And what had happened to the brave men who had stood up to them once upon a time? The survivors have all become obsequious clerks, and I was among them.

I almost did not get out of that valley; one night, they came down the mountain, slithering on the grass and tossing grenades all over the place. “I was lucky,” I said aloud. “Thanks to an old forty-five which I still keep …”

I’ve had this unlicensed gun for years and almost shot an American advertising client with it. When martial law was declared and the government demanded the surrender of all guns of high caliber, I hid it instead in a more secure place — under the panel, close to the floor, of my bookshelf.

“Now, you know it,” I told her. “I hope you will not report me to the Constabulary.”

“I can blackmail you,” she said brightly. Then her face clouded and she seemed pensive. “Each one of your generation seems to have a Japanese horror story,” she said. “Will you believe it, will you be horrified if I told you that my father was a Japanese soldier?”

I gazed at the bright brown eyes, the serene face, and briefly, there came to mind, the faces of the Japanese dead which we had left at the Pass, their bodies bloated, their uniforms rotted. I remembered, too, the neatly uniformed officers — in gold braid, swords by their sides, brown leather boots shiny in the sun — and here she was, claiming kinship with them. If this was 1945, I don’t know how I would have reacted — perhaps with more than loathing. But this was 1974—and for many of us, the war was no more than a memory. What was done was done.

Still, I was more than surprised. “Looking at you, and being with you like this — it is difficult to believe,” I said.

I knew so little of her past and every bit about it that she revealed had an aura of fiction. Could this be one of them? I did not know where she was born, or anything about her education, but because she spoke French and Spanish, I was sure she was not educated in some diploma mill or cheap public school. If her father was a Japanese soldier, how come then that her family was Rojo, not Yamamoto or some such? However, I had no choice but to believe her for I was certain she was not lying or making up a story.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Three Filipino Women»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Three Filipino Women» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Three Filipino Women» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.