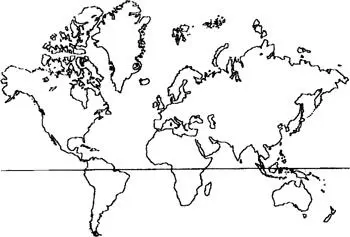

The World Map

The equator did not cross the middle of the world map that we studied in school. More than half a century ago, German researcher Arno Peters understood what everyone had looked at but no one had seen: the emperor of geography had no clothes.

The map they taught us gives two-thirds of the world to the North and one-third to the South. Europe is shown as larger than Latin America, even though Latin America is actually twice the size of Europe. India appears smaller than Scandinavia, even though it’s three times as big. The United States and Canada fill more space on the map than Africa, when in reality they cover barely two-thirds as much territory.

The map lies. Traditional geography steals space just as the imperial economy steals wealth, official history steals memory, and formal culture steals the word.

In Cuba street violence has also grown, and prostitution has flourished, ever since the country’s Eastern European allies collapsed and the dollar became the island’s currency. For forty years Cuba was treated as a leper for the crime of having built in this hemisphere a society based more on solidarity and less on injustice. In recent years, that society has lost most of its material base of support: the economy is out of whack, the tourist invasion has warped people’s daily lives, work has lost its value, and the dolorous traitors of yesterday have become the dollar-are-us traders of today. Despite these recent sorrows, even the revolution’s bitterest enemies admit that some of its achievements still stand, above all in education and health. The mortality rate for Cuban children, for example, is half that for the young of Washington, D.C. Fidel Castro is still the political leader who speaks forbidden truths to the world’s rulers and the one who most insists that the ruled must unite. As a friend just back from Cuba told me, “There are shortages of everything — except dignity. That they have in such quantities they could give out transfusions.” But the crisis in Cuba and the island’s tragic isolation have stripped bare the limitations of a top-down system that hasn’t shaken the bad habit of believing things do not exist unless they’re mentioned in the official press.

Scrawled on City Walls

I like night so much, I’d throw a blanket over day.

True, crickets don’t work. But ants can’t sing.

My grandmother said no to drugs. And she died.

Life is a disease that goes away on its own.

This factory smokes birds.

My dad lies like a politician.

No more action! We want promises!

Hope is the last thing we lost.

We weren’t asked about coming into the world. But we demand to be asked about living in it.

There’s a different country somewhere.

The nine U.S. presidents who have screamed successive condemnations of Cuba for its lack of democracy have done nothing more than denounce the consequences of their own acts. It was the ceaseless aggression and the long, implacable blockade that drove the Cuban revolution to become more and more militarized, far removed from the model that was originally envisioned. The omnipotence of the state, which began as a response to the omnipotence of the market, ended up succumbing to the impotence of the bureaucracy. The revolution sought to grow by transforming itself, and it spawned a bureaucracy that reproduces by repeating itself. At this point, the internal blockade, the authoritarian blockade, is turning out to be just as much of an enemy as the external imperial blockade, stifling the creative energy of the revolution. Many Cubans have lost their opinions for lack of use. But others are not afraid to speak and are eager to act. Thanks to their encouragement, Cuba is alive and kicking, offering proof that contradictions are the heartbeat of history, no matter how badly that sits with those who view them as heresies or as wrenches that life throws into the best of plans.

For much of the twentieth century, the existence of the Eastern bloc, so-called real socialism, encouraged the independent forays of countries that wished to escape the trap of the international division of labor. But the socialist states of Eastern Europe had a lot of state and little or nothing of socialist. When they fell, we were all invited to the funeral of socialism, but the undertakers were mistaken about who had died.

In the name of justice, so-called socialism had sacrificed freedom. The symmetry is revealing: in the name of freedom, capitalism sacrifices justice day in, day out. Are we obliged to kneel before one of these two altars? Those of us who believe that injustice is not our immutable fate have no reason to identify with the despotism of a minority that denied freedom, was accountable to no one, treated people as children, and saw unity as unanimity and diversity as treason. Such petrified power was divorced from the people it ruled. Perhaps that explains the ease with which it fell, without pity or glory, and the rapidity with which a new power emerged featuring the same personalities. Bureaucrats turned a quick somersault and in a flash reappeared as successful businessmen and mafia capos. Moscow now has twice as many casinos as Las Vegas, while wages have fallen by half and in the streets crime grows like a mushroom after a rain.

The Other Globalization

The Multilateral Agreement on Investment, a new set of rules to liberate the circulation of money, was a sure thing at the beginning of 1998. The most-developed countries had negotiated the accord in secret and were ready to impose it on all the others and on the bit of sovereignty those countries still retained.

But civil society broke the news. Using the Internet, alternative organizations managed to ring alarm bells throughout the world and pressure governments to good effect. The accord died unhatched.

We are in the midst of a tragic but perhaps healthy crisis of convictions — a crisis for those who believed in states that claimed to belong to everyone but were really of the few and ended up being no one’s; a crisis for those who believed in the magic formulas of the armed struggle; and a crisis for those who believed in political parties that went from withering denunciations to bland platitudes, that began by swearing to bring down the system and ended up administering it. Many party activists now beg forgiveness for having believed that heaven could be built. They work feverishly to erase their own footprints and climb down from hope as if hope were a tired horse.

End of the century, end of the millennium, end of the world? How much unpoisoned air do we have left? How much unscorched earth? How much water not yet befouled? How many souls not yet sick? The Hebrew word for “sick” originally meant “with no prospect,” and that condition is indeed the gravest illness among today’s many plagues. But someone — who knows who it was? — stopped beside a wall in the city of Bogotá to write, “Let’s save pessimism for better times.”

In the language of Castile, when we want to say we have hope, we say we shelter hope. A lovely expression, a challenge: to shelter her so she won’t die of the cold in the bitter climate of these times. According to a recent poll conducted in seventeen Latin American countries, three out of every four people say their situation is unchanged or getting worse. Must we accept misfortune the way we accept winter or death? It’s high time we in Latin America asked ourselves if we are to be nothing more than a caricature of the North. Are we to be only a warped mirror that magnifies the deformities of the original image: “Get out if you can” downgraded to “Die if you can’t”? Crowds of losers in a race where most people get pushed off the track? Crime turned into slaughter, urban hysteria elevated to utter insanity? Don’t we have something else to say and to live?

Читать дальше