A hit soap opera is generally the only place in the world where Cinderella marries the prince, evil is punished and good rewarded, the blind recover their sight, and the poorest of the poor receive an inheritance that turns them into the richest of the rich. These “big snakes,” as they are called because of their many episodes, create an illusory space where social contradictions dissolve in tears or honey. Religious faith promises you a ticket to paradise in the afterlife, but even atheists can get into the soap at the end of a workday. This other reality, that of the characters, takes the place of ordinary reality for as long as each episode lasts, and during that magical time television is a portable temple that offers escape, redemption, and salvation to souls without shelter. Someone, I don’t know who, once said, “The poor adore luxury. Only intellectuals like to see poverty.” All poor people, no matter how poor, are invited into the sumptuous settings of the soaps, becoming intimates of the rich in their moments of pleasure as well as their bouts of misfortune and tears: one of the most popular Latin American soap operas of all time was called The Rich Cry Too.

The intrigues of millionaires constitute the usual plots. For weeks, months, years, or centuries, the people in the telebalconies bite their nails, waiting for the mistreated young servant girl to learn that she is really the daughter of the company president and to beat out the nasty rich girl for the hand of the handsome young man of the house. The poor girl’s endless suffering, her unrequited love, her lonely tears in her servant’s room are interspersed with entanglements on the tennis court, at pool parties, on the stock exchange, and in the company boardroom, where other characters also suffer, and sometimes kill, to gain a controlling share. It’s Cinderella in the time of neoliberal passion.

God is dead. Marx is dead.

And I don’t feel so well myself.

— WOODY ALLEN

THE END OF THE MILLENNIUM AS PROMISE AND BETRAYAL

In 1902, the Rationalist Press Association of London published a New Catechism in which the twentieth century was baptized with the names Peace, Freedom, and Progress. Its godparents predicted that the newborn would liberate the world from superstition, materialism, misery, and war.

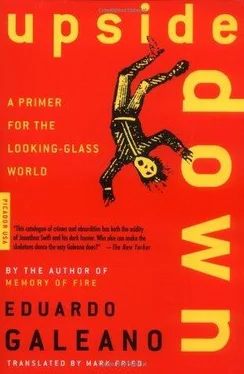

Years have passed, the century has turned. What world has it left us? A desolate, de-souled world that practices the superstitious worship of machines and the idolatry of arms, an upside-down world with its left on its right, its belly button on its backside, and its head where its feet should be.

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS THAT POSE MORE QUESTIONS

Faith in the powers of science and technology fed expectations of progress throughout the twentieth century. When the century was halfway through its journey, several international organizations were promoting the development of the underdeveloped by handing out powdered milk for babies and spraying fields with DDT. Later we learned that when powdered milk replaces breast milk it helps babies die young and that DDT causes cancer. At the turn of the century, it’s the same story: in the name of science, technicians write prescriptions for curing underdevelopment that tend to be worse than the disease, and in the process they humiliate people and annihilate nature.

Perhaps the best symbol of the epoch is the neutron bomb, the one that burns people to a crisp and leaves objects untouched. A sad fate for the human condition, this time of empty plates and emptier words. Science and technology, placed at the service of war and the market, put us at their service: we have become the instruments of our instruments. Sorcerer’s apprentices have unleashed forces they can neither comprehend nor contain. The world, that centerless labyrinth, is breaking apart, and even the sky is cracking. Over the course of the century, means have been divorced from ends by the same system of power that divorces the human hand from the fruit of its labor, that enforces the perpetual separation of words and deeds, that drains reality of memory, and that turns everyone into the opponent of everyone else.

Stripped of roots and links, reality becomes a kingdom of count and discount, where price determines the value of things, of people, and of countries. The ones who count arouse desire and envy among those of us the market discounts, in a world where respect is measured by the number of credit cards you carry. The ideologues of fog, the pontificators of the obscurantism now in fashion, tell us reality can’t be deciphered, which really means reality can’t be changed. Globalization reduces international relations to a series of humiliations, while model citizens live reality as fatality: if that’s how it is, it’s because that’s how it was; if that’s how it was, it’s because that’s how it will be. The twentieth century was born under a sign of hope for change and soon was shaken by the hurricanes of social revolution. Discouragement and resignation marked its final days.

Injustice, engine of all the rebellions that ever were, is not only undiminished but has reached extremes that would seem incredible if we weren’t so accustomed to accepting them as normal and deferring to them as destiny. The powerful are not unaware that injustice is becoming more and more unjust, and danger more and more dangerous. When the Berlin Wall fell and the so-called Communist regimes collapsed or changed beyond recognition, capitalism lost its pretext. During the Cold War, each half of the world could find in the other an alibi for its crimes and a justification for its horrors. Each claimed to be better because the other was worse. Orphaned of its enemy, capitalism can celebrate its unhampered hegemony to use and abuse, but certain signs betray a rising fear of what it has wrought. As if wishing to exorcise the demons of people’s anger, capitalism, calling itself “the market economy,” now suddenly discovers its “social” dimension and travels to poor countries on a passport that features its new full name, “the social market economy.”

For a Course on the History of Ideas

“Manolo, how you’ve changed your thinking!”

“No, Pepe, not at all.”

“Yes, you have, Manny. You used to be a monarchist. Then you supported the Falange. Then you backed Franco. After that, you were a democrat. Not long ago you were with the socialists and now you’re on the right. And you say you haven’t changed your thinking?”

“Not at all, Pepe. My thinking has always been the same: to be mayor of this town.”

The Stadium and the Boxes

In the eighties, the Nicaraguan people were sentenced to war for believing that national dignity and social justice were luxuries to which a poor little country could aspire.

In 1996, Félix Zurita interviewed General Humberto Ortega, who had been a revolutionary. How quickly times have changed. Humiliation? Injustice? That’s human nature, said the general. No one is ever satisfied with what he gets.

Читать дальше