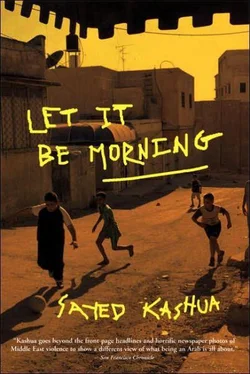

It hasn’t been long since we moved back here, but I can go into stores in the village center without being questioned, as if I’ve been shopping there all along. People are less suspicious. Some of the salespeople recognize me by now and greet me when I walk in. The first time I went to buy a falafel, for instance, the vendor didn’t ask me a thing. He just looked at me, studied me and decided I was a stranger. I tried to be polite, the way a stranger ought to be. The second time he felt he could ask me whether I was a local. When I said I was, he wanted to know whose son, what I did for a living, whether I knew so-and-so, who my wife was, whose daughter she was, what she did. The third time, he felt he could inquire how much I made at the paper and how much my wife made as a teacher. I lied. The figures I gave were much too high. Twice the highest salary I ever made at the paper when I was on the editorial board. I could afford to lie, about journalism at least. Nobody has a clue how much a journalist makes. When it comes to teachers, on the other hand, everyone knows the answer.

I don’t like being questioned this way by salespeople, some of whom are half my age. I’ve never asked anyone how much he or she makes a month, it’s been more than ten years since I’ve discussed my personal life with a salesperson and I’ve almost forgotten how it goes here. Other salespeople or just people who happened to be waiting in line at the bank or the pharmacy or the infirmary, as soon as they find out who I am, also want to know what I’ve been doing all these years, what it was like to live in a Jewish city. Did I have any male children? Almost invariably, the people who interrogated me declared that coming back to the village was a smart move. They found it hard to understand how anyone could live anywhere else. They looked at me as if I were an alien and congratulated me on my decision to return. “Is there anything better than living among your own? With your family?” was something I heard over and over again.

I hate those situations, and I sometimes get annoyed at my wife for making me do the kinds of chores that force me to keep going down to the center and to bump into people. I’d prefer for her to do those things instead, but I know it would be considered odd. Fact is, I’ve never seen a woman at any of those stores, and if there were any, she was usually there together with her husband or a male relative. An Arab woman would never go out to buy hummus or falafel on her own. It was unthinkable. The first time I was made to go down to the center of the village, it was to fix my wife’s wedding ring. One of the stones had fallen out three weeks earlier, and I couldn’t procrastinate any longer. She just went on and on about that stone and that ring. She said it was a bad omen, that the damage to the ring was mostly a sign that there was something wrong with our marriage, which was falling apart. I reached the iron gate. I tried to push it in, but in vain. The gate was locked. The salesperson sitting on the inside looked at me, tilted his head forward, and through the loudspeaker of the intercom next to the gate I could hear him ask, “Who are you?” Only after I gave him my name, my father’s name and my last name did he smile and press the button and signal me to push the gate, which gave off a squeaky sound. Another iron gate came next, but so long as the first one was not completely shut, he didn’t press the button that would open the second one. For a few very scary seconds I was locked in a steel cage. This place must have been robbed a million times, I thought.

“Ahalan u-sahalan,” the salesperson greeted me, getting up and taking my hand. “I’ve heard about you. You just returned to the village a short while ago, right? You may not know this, but your father and I used to be close friends. Nowadays, because of business, we hardly see one another, but he’s like a brother to me.” The salesperson looked my father’s age. His large head was covered with white hair and his enormous body filled the pink director’s chair on the other side of the counter. All of the gold in front of him was yellow, shiny. On the back of the chair he had placed a green prayer mat with two mosques depicted on it. In his one hand he shifted the beads on his masbakha as he inquired about me and my wife, expressed his approval of our return and asked how he could help. I handed him the ring. He said it was nothing, he could fix the damage on the spot, in just a few minutes. My parents had bought the ring from him. He told me they had bought the jewelry for my brother’s wedding from him too. “I have the best merchandise anywhere around here, and I gave your father a great price, same as I’d give my own brother.”

The wedding jewels replaced money as the groom’s mohar payment, and represented a pretty big expense for the groom’s parents. The salesperson felt obliged to note that my parents had not skimped and had bought the most expensive ones. Both for my wife and for my older brother’s. “I want you to know,” he said, “that your parents are exceptionally fair. They bought your wife the very same things they bought for your older brother’s wife, and it’s only a wise person like your father who’d do that, because you know how it is, women look at one another and get jealous. They did the smart thing. They asked for the identical set for your wife. I had to place a special order.” He laughed. Me he’d never seen before, maybe when I was little, he said. But he saw my father and my older brother in the mosque every Friday. “Tell me,” he asked as he handed me back the ring, “which mosque do you pray at?”

“At home,” I muttered. “I pray at home.”

“I guess you haven’t had a chance to get to know the mosques around here. I’m telling you, come to our mosque, together with your brother. That would be the best. We don’t have a lot of politics, or a lot of fanatics. I know your family, it’s what would suit you best. Your family are like us, not like some of those crazies.”

Yesterday, two more stones fell out of the wedding ring, the one I had fixed recently, and another one. My wife wants me to go have it fixed again, even though she figures it probably won’t hold.

Ipass by the mosque, which means I’m back in my own neighborhood already. The older people at the entrance don’t seem the least bit worried. Rolling their Arab tobacco and licking it tight, huddling there together all day waiting for the next prayer hour. What else do they have to do, actually? At least they don’t feel alone, and they can spend hours talking about people who died two thousand years ago. I blurt out a salam aleikum to which they respond with an aleikum salam, and I raise my hand. I’ve got to calm down. Truth is, I’m much calmer already. Some bulldozer must have slashed a cable and all the mobile phones went dead because the lines were jammed. Maybe an antenna has been damaged. Everything will be all right. Maybe I shouldn’t go to my parents’, maybe I ought to check the exit first, see if the roads are open already and retrieve my car. People in the street don’t seem to think it’s anything serious. There’s cheerful music inside the houses, Egyptian pop. I recognize it and it makes me happy, even though, on the whole, I hate the trend. Every now and then, a car drives by and brakes just before the makeshift speed bumps that were put there to deal with reckless young drivers and car thieves who like to show off their loot by racing through the streets at crazy speeds. Some of the neighbors simply poured cement down in the shape of a small mound opposite the house, while others preferred to slow things down by digging a ditch from one side of the road to the other. Housewives are mopping the house and pouring the dirty water into the street, the way they do every morning. Where on earth, I ask myself, did I get the idea they were closing off the village?

Читать дальше