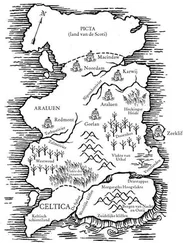

It was later, lying supine and blind for days, faced with the choice of either inventing internal worlds or having no world at all to inhabit, when I started to fill in the details: how the planet had been ruined (reactor five); how the cities had been emptied (mutant hominids from sea caves seeking out coastal cities for uncontaminated flesh, and continuing to move inland, spreading disease and killing innocents); where and how the surviving humans had built the Trace Italian (far inland, with their bare hands, from available materials cut and tumbled and hewn and polished over generations for several hundred years). How it rose from the landscape, bigger than its medieval counterparts, a shining structure on the plains, protecting the sprawling self-contained city underneath it, a barrier against the outside world and a sign to would-be intruders that its architects were people of great vision and design. Thinking of games as a way to kill time in history class had been one thing, but filling out the map and telling the story of every spot on it by myself, in my head, on my back: it was a refuge for me. I identified with the people I’d created to populate the barren landscape. I shared their goal: to find the location of the Trace Italian. Work through the ant-leg limbs of the star layer by layer until you find the shining heart. Get there at last. Stay there.

I identified with the seekers to the point of imagining myself as one among their numbers. Pushing myself against the wall-rail down the hall to the shower room, I would picture myself scurrying shirtless through the few gutted buildings that remained in the slumping cities, whistling signals to the others who crawled across the crossbeams; served lunch, I would imagine that I was foraging for untainted canned foods, coughing through dust that rose from the shelves of a grocery store on an empty block in a long-depopulated city. Lying in my bed, I would think: I have been wounded en route to the Trace Italian. I am going to have to heal myself, or limp to safety. Get up. Get up. Get up.

One day one of the nurses caught me sketching a dungeon, one of the innumerable and potentially terminal signal stops on the road to the star fort, and she looked at it over the siderail for some time, scrunching up her brow. I could feel her, scrutinizing my work, her eyes following the spindly arms of a mutated star, and then looking at my face as my undistracted bandaged hands determinedly cornered right angle after right angle. I knew she wanted to ask what I was doing, but I had the advantage. Nobody liked to see me speak.

The way you play Trace Italian seems almost unbearably quaint from a modern perspective, and people usually don’t believe me when I tell them it’s how I supplement my monthly insurance checks, but people underestimate just how starved everybody is for some magic pathway back into childhood. Trace Italian is a mail-based game. A person sees a small ad for it in the back pages of Analog or The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction —maybe he sees the ad month after month for ages — and then one day he gets bored and sends a self-addressed stamped envelope to Focus Games, and I send him back an explanatory brochure. The brochure gives a brief but vivid sketch of the game’s imagined environment — no pictures, just words — and explains the basic mechanics of play: a trial subscription buys you four moves through the first dungeons, and five dollars a month plus four first-class postage stamps keep a subscription current. I boil down handwritten, sometimes lengthy paragraphs that players send me to simple choices — does this mean go through the door , or continue down the road ? — and then I select the corresponding three-page scenario from a file, scribble a few personalized lines at the bottom, and stuff it into an envelope. They respond with more paragraphs, sometimes pages, describing how they move in reaction to where they’ve landed. Eventually they recognize the turns they’ve taken as segments of a path that can belong only to them.

A player’s first move isn’t necessarily the truest or clearest view of that person I’ll get, but it’s often the most naked, because it takes a while to situate yourself within an imaginary landscape. When you respond to the initial subscriber packet with your opening move — when you come to the bridge — you haven’t had a chance to get much sense of the game’s rhythms, so you’re awkward, halting, more likely to overplay your hand. The open path at the overpass gives way to grand schemes, huge, multipart responses, whole narratives from within the canvas newly forming inside the player’s imagination. I keep myself out of it; I interpret and react, like a flowchart responding flatly to a person who’s asking it how to live.

I did it this way for years, mechanically helping people through the chambers of my original hospital vision, occasionally even typing out fresh moves one page at a time on an IBM Selectric, my face hot with bandages, the work distracting me from my circumstances. The advent of the internet looked like it would kill off the game, and I wondered what I’d do for work, but people will surprise you. By 2003—long after most of the magazines that had served as initial points of entry had stopped publishing, the few left displaying my ads to fewer and fewer subscribers — the number of dedicated players had risen to the mid-hundreds, none of whom were at all interested in shifting their daily play over to video games or MMORPGs. My rate had risen with the times, to ten dollars a month. There were websites that scanned and posted as many moves as they could collect, but not many people interested in seeing the moves out of turn: the point was the play. And beyond all that, plenty of people had been involved too long to turn back. Their quiet fervor attracted a few new curious seekers each month, and the replacement rate was more or less constant — people sometimes grew out of the game or got frustrated with their progress, but a few more always came along to take their place. The core was committed. Their minds were made up. They meant to reach the Trace Italian. They thirsted for the security it offered, for the sanctuary of the interior.

The inside of the Trace Italian, of course, does not exist. A player can get close enough to see it: it shines in the new deserts of Kansas, gleaming in the sun or starkly rising from the winter cold. The rock walls that protect it meet in points around it, one giving way to another, for days on end. But the dungeons into which you’ll fall as you work through the pathways to its gates number in the low hundreds, and if you actually get into the entry hall, there are a few hundred more sub-dungeons before you’ll actually reach somewhere that’s truly safe. Technically, it’s possible to get to the last room in the final chamber of the Trace Italian, but no one will ever do it. No one will ever live that long.

I opened about a dozen envelopes today; the process has been the same for years. First, I open as many as I think I can take care of in one sitting. Then I stack them on the floor by the desk, letters and SASEs still inside, and I sit down next to them. It makes me feel young. And then I deal with it all: methodically, almost mindlessly sometimes, one by one until there aren’t any left. Most days it’s all Trace Italian, but some days there’ll be stragglers: maybe the Pennsylvania kids who answered an ad in a yellowing magazine they’d found at the Goodwill just to see what would happen, and who now competed against each other in an otherwise wholly abandoned game called Rise of the Sorcerers. War game fiends playing through Operation Mercury for the third or fourth time. Or one of the seven people who still play Scorpion Widow, who may well keep playing forever somehow, no matter what happens to me. Two today. Sometimes I let my mind drift out a little: I try not to get carried away, and I have to be careful, but I wonder about them, the servants of the scorpion widow — who they really are, what they’re like. If they contemplate growing old along with their subscriptions. Maybe they’ll go missing one day, stuck forever in the sands where they made their last move. Gone. Who might they be elsewhere: in their rooms, alone with pencils, working on maps. Why they play, why they’re still here. What it means to them.

Читать дальше