The art therapist came in fairly early on, or what feels now like it must have been fairly early on. I was in no condition. I was running a temperature they couldn’t figure out; it came and went. But I was awake some of the time, and that was enough. She stuck to simple questions: “Do you like to paint?”

“Not really.”

“Puzzles?”

“Sometimes.”

“Do you like to draw?”

“Yes.”

“Good! What kinds of things do you like to draw?”

I looked up to where I’d been looking, where I’d still be looking long after she left. I felt warm. “The universe,” I said, with a little effort.

People have ideas and theories about coping with catastrophic injury, but most of them are based in practicalities. They’re right in thinking that the practicalities — how will you live? what will you do? — are important, but these aren’t the main thing. The main thing is what happens to your vision, how you’re a little different after you’ve seen a few things, and as far as I know, nobody really gets this, though I thought Chris Haynes did once. Something in his overall distrust of the path going forward felt moored to some bigger thing I knew about, something he’d either inferred from the play or known instinctively. But maybe not. It’s hard to say.

One way of coping, anyway, is to stare at the ceiling. A hospital room ceiling, white, like an egg in a carton that’s been in the refrigerator for several weeks, away from the light, is dull, completely uniform, revealing variations only when you stare at the same spot for some time and then, very slowly, venture out. If you concentrate hard enough on the task, you might find a bubble or grain where a brush or a roller has stopped to reverse its stroke. You could let your attention rest there for a while; you could imagine the future of the ceiling, the battles playing out up there, camps pitched when the building was new back in unremembered time. You could picture the paint beginning to crack and fragment, and see, either in your mind’s eye or out there on the actual field of play if your vision spreads that far, the plaster underneath it learning to follow the cracks, the mildew forming on residues left by cleaning solutions beginning to breed, and colonies of microscopic life-forms, hostile to dull matter, developing their ruthless, mindless strategy: consume, reproduce, survive. You can see the hospital when the building has been emptied of patients but a few workers remain: administrators, janitors, members of the demolition crew. You can see the ceiling in the next room, following the splits of the ceiling in its neighbor, and the one beyond that in turn, and then the greater canvas, the sky at night gone flat and painted white, the constellations in the cracking paint, the dust the cracks bring into being as they form, finding free land where none had been before their coming.

Nurses and doctors come and go, and family. It’s like they’re visiting a person at his lonely outpost on the space station, miles above the earth. How do they get there — just coming in through the door like that? In the brief moment between infinite communion with the ceiling and the beginning of whatever conversation they’ve come to strike up, it seems like the deepest mystery in the world. And then they break the spell, and the world contracts, palpably shifts from one reality into a new and much more unpleasant one, in which there is pain, and suffering, and people who when they are hurt stay hurt for a long time or sometimes forever, if there is such a thing as forever. Forever is a question you start asking when you look at the ceiling. It becomes a word you hear in the same way that people who associate sound with color might hear a flat sky-blue. The open sky through which forgotten satellites travel. Forever.

So when I remember the ceiling I try to invest it with meaning somehow. I try to connect its cracks and bubbles to palpable things out there in the world, to things I might have run across later. I treat the imperfections like tea leaves. I remember it as vividly as I can, and I look for shapes in things too small to have any visible shape, and I see centaurs or cavemen or trowels or piles of bricks, and I try to draw lines between the shapes and the slow sweet life I built for myself when I finally got out and learned I wasn’t, thank God, welcome at home anymore. But eventually I locate what I’d known I’d find up there all along, what I’d been seeing already in brief seconds of lucidity arising from the murk of those nights become days and those days of no light. I see my own face. I see it as it was, preserved in stray signals too late to read right.

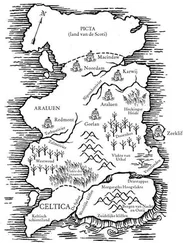

I’m pretty sure that’s the lesson there was to learn in the hospital: the main one. And I’m pretty sure my play was the right one to make. Because the unnamed every-player who lies in the weeds at the moment of Trace Italian’s opening move — that’s me. It’s me. Motionless, ready for something, awake and aware. When the player gets up from the weeds, as he or she always does, because the first move is rigged and all players arrive persuaded that they must act, everything changes: He enters a world where danger’s everywhere. He has a goal now, something to do with his life. His map is marked; he’s headed somewhere as he rides down the desolate plain.

But this is the point where we split, the player and I. He heads for the road to seek shelter or something to eat. But I remain in the stasis of the opening scene, bits of gravel sticking to my face, cold night coming on. I am strong enough to endure it. I am strong enough to remain in its arms forever. I won’t get up; I have seen the interior once. I’m not going back. One thing I’ve learned is it’s better sometimes, in the weeds, to resist the temptation to stand up and follow the compass.

Years later when they made me look at pictures of Lance and Carrie I remembered Marco, the empty, incoherent prophecy I’d heard amid the chaos. For a second, as I flipped through the evidence, my long-forgotten hallucination became real, and I wondered how he’d managed to remain hidden for so long. What if I’d tried to talk to the doctors about him; why hadn’t my mind offered him up as a way to get them off my back? I’d had plenty of encouragement. “Who made you do this, Sean?” my father asked at my bedside, my hand in his. I thought then how nice it would have been to have a good answer ready to give to him, a little gift from son to father, something he could take to his friends by way of explanation. To blame Marco. To lay it at his feet.

“Have you seen these people before?” the attorney asked me in the conference room, running through the planned stations of his performance, giving Carrie’s parents their money’s worth. He fanned several photographs across the table in front of me and waited for my reply. But they were impossible to understand, all of them and each of them; they belonged to a context that couldn’t be referenced outside of itself, incredibly important in one way and completely meaningless in another. They were artists’ renditions of somebody’s dream. What could I say? Sure I have, a long time ago. You wouldn’t understand.

There are games I’m prouder of than Trace Italian but it doesn’t really matter how I feel. Trace Italian is what built Focus Games, and if people know my name at all, Trace Italian is why they know it. It was my first idea; they say your first ideas are your best ones. I think it’s maybe dangerous to think that way all the time. But when I remember finally building Trace Italian, seeing how it was actually going to come together and really work, then I know what people mean about their first ideas being the best. There is something fierce and starved about first ideas.

I’d harbored the Trace concept for a long time — I think I was inspired by a commercial for an old board game called Stay Alive. It starred a bunch of kids playing on a beach; there were no adults around, and waves crashed angrily against rock cliffs nearby. The children pushed or pulled levers on a playfield, opening holes in the board as they did so; eventually all marbles on the board except one would drop out of play, and then the winner would announce, in a breathless voice that suggested he couldn’t believe his luck: “I’m the sole survivor!” It held my attention. As a child I wanted everything to be in some way concerned with endings. The end of the world. The last Neanderthal. The final victim. The stroke of midnight. So children playing a game called Stay Alive on a beach with nobody else around, that spoke to something in me, something I’d maybe been born with. Of the many logos for imaginary products I would come to design throughout high school, Trace Italian was the first. I’d gotten the name from dry days in history class during a lesson on medieval fortifications: anything that involved the word star always sounded like it was speaking directly to me. The trace italienne involved triangular defensive barricades branching out around all sides of a fort: stars within stars within stars, visible from space, one layer of protection in front of another for miles. The World Book preferred the term star fort , which I also liked, but in idly guess-working trace italienne into English I’d stumbled across a phrase that had, for me, an autohypnotic effect. TRACE ITALIAN. I would spend hours writing and rewriting the name in stylized block capitals, reticulated line segments forming letters like the readout on a calculator. On notebook paper rubbed raw with erasures, the evolving logo resembled a department store’s name spelled out in dots and dashes on cash register tape: RILEYS UNIVERSITY SQUARE. The driving image for my game involved people running for shelter across a scorched planet. There was something on fire in the near distance behind them. Their faces looked out from the page toward their goal. The Trace Italian represented shelter, and it was shaped like a star. That was all I had.

Читать дальше