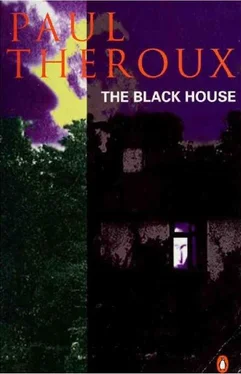

Paul Theroux - The Black House

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Paul Theroux - The Black House» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1996, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Black House

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1996

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Black House: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Black House»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Black House — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Black House», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

At eleven sharp he heard the commotion, the horns,

the hoof-thumps, the yapping hounds, and all day the hunt went back and forth behind the Black House. For periods there was no sound, and Munday waited; then a horn brayed and brought the hunt back, the muffled gallop of the horses and the shouts of the people chasing after. They were circling the house, the pack of hounds driving the fox across Munday’s fields. It raised his old fear of being hunted; but recognizing it he saw his distance from it. The sound of the hunt kept him from working. He examined his fear. It was like the memory of a breakdown, which, even after it ceases to disable, can still cause pain in the recollection; not erased but made small, the vision of a frightened man at the periphery of his mind, distress into humiliation, fear into lumpish frailty. Now the horns blared again and the hounds responded with maddened barks. He had been tricked about his heart, but he remembered the fingers of fire in his chest: he had believed himself to be ill as he had believed the shadows in the Black House to be fatal for him. The remembrance of the illness only brought him to selfcontempt, and he raged at the disruption of the hunt Mrs. Branch watched from the kitchen, Emma from an upper window; Munday bore it in his study, pretending to work. In the early evening the noise lessened, but just as Munday returned to his book he heard a car door slam and the bangs of the brass knocker. Then Mrs. Branch at the study door: “There’s a man outside says he wants to see you.” He went out and saw the dagger. But he didn’t touch it, for it was jammed to the metal of its hilt into the throat of a blood-spattered foxhound.

“Is this yours?” the huntsman had asked, opening the lid of the car’s trunk. He pointed with a short whip, slapping the thong against the corpse.

“The knife yes,” said Munday. “The dog no.”

“We want an explanation,” said the man.

“So do I,” said Munday, bristling at the man’s accusation.

“That dog was valuable.”

“The dagger’s worth something as well,” said Munday. “It was stolen from me several months ago.”

“Stolen you say?” The man flexed his whip.

“Yes, but how did you know it was mine?”

“I didn’t. This happened on your land—in the back. One of our whippers-in found him.”

“Bad luck,” said Munday. He reached for the dagger, but the man laid his whip on Munday’s arm. Munday glared at him.

“Not until we find out who did it,” the man said. “Quite obviously, one of your own people.”

“There’ll be fingerprints on it.”

“Of course. Fingerprints,” said Munday with as much sarcasm as he could manage. “I’d forgotten about those.”

“We’ll get to the bottom of it.”

“I hope you do. Mind you, I want that dagger back.”

“What a vicious thing.”

“Purely ceremonial,” said Munday, who saw that the man meant his comment to reflect on him. “It wasn’t designed for killing. Africans don’t kill animals with knives. They can’t get close enough for that.” Emma came out of the house with a sweater over her shoulders. She shivered and tugged the sweater when she saw the dead dog; she said, “Oh, God, the poor thing.”

“My best hound,” said the man, and he gave it an affectionate pat on its bloody belly. “The rest of the hunt know about it—we’re all livid. It’s the first time anything like this has happened.”

“It’s terrible,” said Emma.

Munday said, “I agree, but I want you to understand that dagger is extremely important to my research.” My dog, my dagger: the two men bargained, as if haggling over treasures, pricing them with phrases of sentiment, insisting on their value, the dead dog, simple knife.

“Your knife, on your property.”

“You don't think Alfred had anything to do with it, do you?”

“I don’t know, madam. I’m reporting it to the police, though.”

“You do that,” said Munday.

“I’m not treating it as an ordinary case of vandalism.”

“I shouldn’t if I were you,” said Munday. “And I suggest you catch the culprit. It’s clear he had a grudge against me.”

“Really?” The man slapped his whip against his palm.

“One of these rustic psychopaths, trying to discredit me in some fumbling way. It's possible.”

“Why would anyone want to do that?” asked the man.

‘Thaven’t the slightest idea.”

“There must be a reason.”

“Don’t look for a reason, look for a man. Munday’s law. Now if you’re quite through—”

“I was simply asking,” said the man. “If there’s a reason the police will know what it is before long.” He banged the trunk shut, said goodnight to Emma, and drove off.

Emma said, “Why were you so short with him?”

“I didn’t like his insinuations,” said Munday. tcl won’t be spoken to like that. Insolence is the one thing I will not stand for. I didn’t come here to be treated like a poaching outsider, and if that person comes back I shall refuse to see him. Do you find this amusing?”

“I’ve heard you say that before.”

“Not here.”

“No,” said Emma. “Not here."

In the house Munday told Mrs. Branch what had happened, and he deputized her: “Keep your eyes skinned and your ear to the ground, and if you hear a word about this you tell me.” The following day at breakfast he looked over his Times and said, “Well, what’s the news?”

And Mrs. Branch, who in the past had always responded to such a question with gossip, said, “Nothing.”

“No one mentioned it?”

“No sir,” she said. “Not that I heard.”

“I find that very hard to believe, said Munday. “You didn’t hear anything about the hunt?”

“Only that they caught a fox out back and blooded one of the girls from Filford way.”

Later in the morning there was a phone call from the vicar. He said, “I just rang to find out how you’re getting on. We haven’t seen much of you. I trust all is well.” Munday said, “I suppose you’ve heard about the dog that had his throat cut?”

There was a pause. Then the vicar said, “Yes, something of the sort.”

“That dagger was stolen in your church hall by one of your Christians,” said Munday. “If the police come to me with questions I shall send them along to you. You can confirm my story.”

“I didn’t realize it was a knife that had been stolen.”

“A dagger,” said Munday. “Purely ceremonial.”

“It’s very unfortunate that this happened so close to your house.”

“I don’t find it unfortunate in the least,” said Munday.“It has nothing whatever to do with me. Was there anything else you wanted?” That was a Friday. No policeman came to investigate, though Mrs. Branch said she saw one on a bicycle pedaling past the house. Munday was being kept in suspense, not only about the dog—which worried him more than he admitted: he didn’t like being singled out as a stranger—but also there was Caroline. He had not heard from her for weeks, and he missed her, he required her to console him. Emma tried, but her consolation didn’t help, and with the admission of her illness, her bad heart, she had stopped making any show of bravery and she had begun to refuse Munday’s suggestions of walks, saying, “No—my heart.” He believed her, and yet her words were an accurate parody of his own older expressions of weakness.

But he took his walks still, and walking alone he often had the feeling he was being followed—not at a distance, but someone very close, hovering and breathing at his back. The suspicion that he was being followed was made all the stronger by his inability to see the hoverer; it was like the absence of talk about the dead dog, the silence in which he imagined conspiring whispering villagers. The walks did little to refresh him: he was annoyed, and it continued to anger him that he was annoyed, so there was no relief in thinking about it—it only isolated his anger and made it grow. And he could be alarmed by the sudden flushing of a grouse, or the church clock striking the hour, or the anguish he saw in a muddied pinafore flapping on a low gorse bush.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Black House»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Black House» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Black House» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.