During one of his father's rare visits to Sweetwater from California, Buddy filled his father's car with sand. It was another practical joke he repeated as he grew older, substituting sand with cat litter, cow manure, and potting soil, and at last expanding industrial foam, which hardened like cement. Technology is the prankster's friend, but so are traditional skills and peasant cunning. Buddy was expert at obtaining smears and swipes of bitches in heat — I did not ask how — and applying these to the clothes of schoolteachers who punished him. His revenge was seeing them besieged by packs of amorous dogs.

Sabotage can be simple. The exploding toilet seat. The potato jammed in the exhaust pipe. Sugar in the gas tank. The collapsing chair leg. Phantom voices on the phone. The dismantled lawnmower. The reusable cockroach. Mail-order madness: a pileup of Sears, Roebuck deliveries. The believable turd. The reversed road sign. The ambiguous classified ad, inviting breathy phone calls. These were practical jokes for the cash-strapped schoolboy. Buddy was soon expelled from school.

He was hired at the family bank and with a little income was able to conduct his first experiments in turning the staff toilet into an aquarium — first eels, then goldfish, then the tropical fish that belonged to the manager, dipping and diving in the hopper. At the very moment he was being berated for this offense, he contrived to slip some glue on his tormentor's chair. Before he could be fired, he was able to smuggle a live pig into the walk-in vault, leaving it to be discovered, dung-smeared and skidding, in the morning.

In themselves, none of these practical jokes were unusual, but their simultaneity gave them force and made them memorable. He was fired from the bank by a man who, later that same day, found another pig in his car. Live pigs were to play a prominent part in many of Buddy's jokes.

Now seventeen, Buddy was sent to live with his father and a new stepmother, who were soon contemplating the significance of an enormous torpedo in their bed when they retired one night. Perhaps a bizarre form of salutation? They knew the perpetrator, of course, but weren't able to discover the means by which he had shunted the half ton of metal. Had they known, they would have rid themselves of it more quickly. The expensive removal took days.

"I think your son is insane," the new wife said.

Putting his finger in his mouth, clownishly playing dumb, Buddy said he knew nothing about it. I was wondering what a psychiatrist would make of the symbolism of the torpedo in the marital bed when I heard of his next embellishment. Buddy insinuated himself in the bed one night when his father was delayed by a ruse Buddy himself had rigged. Buddy was welcomed in the darkness by his stepmother, who took his bulk for her husband's, and it was only after they were engaged in strenuous foreplay that Buddy revealed himself — by braying like a donkey. The woman was too ashamed and humiliated to report him, but before long Buddy was evicted.

Hobbling his friends and family with large, immovable objects was a recurring motif in these jokes of his late teens, as though the object in

question stood for Buddy himself: the gigantic safe sinking into the rain- softened lawn, the anvil in the bathtub, the motorcycle on the roof, the porch swing in the swimming pool. As he grew heavier, Buddy himself became harder to remove. On his twenty-first birthday he was six feet three and weighed 220 pounds.

Incidentally, he was working at a film studio owned by his father, but what seemed like relentless aggression was too much for the man, and Buddy was soon on his own. He was never to return home, and though he looked after his mother for a while in Hawaii when she was senile and near death, he did not see his father again.

At the age of twenty-two he got a job on a merchant ship out of San Francisco, his first joyous taste of the Pacific. But the work was hard, he was a fractious seaman, so he was punished. His revenge: stinky cheese on the hatch handle, the ship's horn blown in the wee hours outside the first officer's cabin, his signature turds in the desk drawers of senior officers.

He knew what was coming; he welcomed it. The Pacific ports, battered by the war and thoroughly corrupted and deranged, were an invitation to Buddy. Put ashore in Noumea for insubordination, Buddy laughed and learned French. In New Caledonia he discovered firsthand France's designs in Indochina — it was 1952 and the French were recruiting soldiers locally. Buddy tended bar and kept a mistress. He was hired as an informant by the CIA, and he thrived.

To Tahiti. He made himself popular with bootleg whiskey and married a sixteen-year-old. The CIA found him and demanded their money back. Buddy gladly gave it to them, two thousand dollars — in pennies.

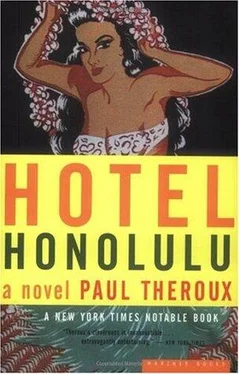

Buddy's practical jokes, essentially vindictive, became for a time inseparable from pure revenge. He was a card player, an irrational and usually successful gambler. He won the Hotel Honolulu in a card game. He made the hotel popular by bringing the first Tahitian dancers to Hawaii, putting on a show on the hotel's poolside lanai. His envious friends, led by Lemmo, intending to deflate him, sealed up his office — bricked in the doorway and painted it.

Buddy broke through. And laughed. He liked the extravagance of it. He declared war, and lodged a telephone pole through the length of Lemmo's house, skewering the whole dwelling through its windows.

Once, returning from Tahiti with some black pearls Buddy had ordered, Peewee was taken in for questioning by the airport police. Buddy had called Honolulu customs and tipped them off that Peewee was an international jewel thief. And often, in an excess of sentiment, he installed live pigs in offices overnight and got fat men to eat "tapeworms" he had dug up in his garden.

The magazine he started, Teen Hawaii, put him in touch with as many pretty girls as his Tahiti show had done, but the magazine failed. For a time his hotel was a meeting place, crackling with Buddy's diabolical energy, but before long othei bigger hotels were built, and his was shoved to the edge of Waikiki.

Claiming at his sendoff dinner that Stella's ashes had been in the pepper mill was a great joke, Buddy thought, but the best by far was his coming back from the dead. Many of his friends said they had guessed the outcome all along, but it put the fear of God into Pinky and made her a compliant wife.

"This is my friend," Buddy said to Pinky, nodding at me. "He wrote a book! Go on, angel, give him a kiss."

She was too shy to kiss me. Looking at her unmarked face, I saw someone who seemed to be entering the world for the first time, and uninterested in it, perhaps even repelled by it. I saw what Buddy meant by "angel": inexperienced, childlike, innocent, just beginning to learn the coarse language of life.

Her posture, the way she hunched her shoulders, was like that of a trapped bird, one captured in the wild and still fluttering with fear, her heart pounding like mad. Her smallness made her seem even younger than twenty-three. She wore a T-shirt, and her blue jeans showed her narrow hips and spindly legs. If a woman is a woman for the alluring way she stands, the opposite of a coquette is an adolescent boy. Wearing a baseball cap, she looked like a Little Leaguer.

"Funny thing," Buddy told me. "She was in the dining room alone this morning. She bumped into the table and the flower vase shook a little. I was in the downstairs john. I heard her say 'Sorry.' To an empty room. Is that beautiful or what?"

Her face told nothing except her age. Her smile was trusting. She was glad to be married. She held Buddy's hand the way one of his children

might have, staying in his shadow like a triumphant pet, as an angel sometimes seems to be.

Читать дальше