As you might imagine, Nina, I am not penning these words in a smooth consecutive flow. Zamenhof’s words are not ingrained in my memory, the history of Esperanto is not at my fingertips, and I have to interrupt my writing every so often to rediscover passages scrawled in notebooks a good few years ago, when I began my Esperanto project, or to consult more fully drafted pieces, stored on the computer. And, as I transcribed Zamenhof’s words from the screen before me, in pen and ink, I felt, as my hand moved across the page, that it was somehow guided by the spirit of Zamenhof, that I felt as he felt, knowing just a little of the linguistic despair that was his, that his words were both his and mine, though written in a different language, for he had written them in Esperanto, not English. And, rewriting those words by hand, I began to see nuances in them I had not hitherto suspected, for my view of them is different now that you have re-entered my life. So much has changed.

While still at school, I had written on the computer, Zamenhof began thinking of a universal language, and by 1878 he had invented one. Five years previously his father had moved with his family to Warsaw, where, in order to supplement his income as a teacher of German in the Veterinary Institute, he took on extra work as a state censor. In 1879, when Zamenhof went off to study medicine in Moscow, he left his extensive notes for the new language in his father’s care. Immediately recognising the danger of possessing such documents, written in a secret language by a poor Jewish student, his father burned them. In Moscow, Zamenhof became involved with Zionism, but grew disillusioned with the movement, which he found too exclusivist. He returned to Warsaw, and to his dream of an international language. Finding it destroyed, he reconstructed it from memory.

In 1886, the year in which he matriculated in ophthalmology, he became engaged to Klara Zilbernik, the daughter of a prosperous businessman. For two years Zamenhof had unsuccessfully sought a publisher for a booklet in which he which described the new language. Klara’s father, impressed by the idealism of his future son-in-law, offered to have the book printed at his expense. This was done; the proofs were held for two months in the censor’s office, but fortunately the censor was a friend of Zamenhof’s own father, who by now had withdrawn his objections to the project. On 14th July 1887 the censor authorised the booklet, and it was published in Russian; Zamenhof soon afterwards translated it into Polish and German. An early follower translated it into French under the title La Langue Internationale .

These editions all contained the same introduction and reading-matter in the international language: the Lord’s Prayer, a passage from the Bible, a letter, poems, the complete grammar of sixteen rules, and a vocabulary of 900 roots. The work was signed with the pseudonym ‘Doktoro Esperanto’ — esperanto meaning ‘one who hopes’ — and the new language, by general usage, became known as Esperanto. Dr Esperanto and Klara Zilbernik were married on 9th August 1887, and the first few months of their life together were spent promoting Esperanto, putting the booklet describing the new language into envelopes and posting them to foreign newspapers and journals. It was known as the Unua Libro , the First Book.

There was no English translation for some time; Zamenhof considered his own English insufficiently adequate for the task. A German friend did produce one, which Zamenhof published, but English speakers found it incomprehensible.

In the autumn of 1887, a certain Richard Henry Geoghegan read an article about the new language. The Geoghegan family lived for many years at 41 Upper Rathmines Road, Dublin. Richard’s father was a doctor who emigrated in 1863 from Dublin to Birkenhead in England, where Richard was born on 8th January 1866. At the age of three he suffered an accident which left him crippled for the rest of his life; but the good Lord, as my father might have said, by way of compensation, gave him extraordinary linguistic gifts: he had a perfect command of French, German, Italian, Spanish, and Latin, and became a noted expert in Chinese, Japanese, Hindi, and other oriental languages. He considered himself an Irishman: he spoke and wrote fluent Irish, and often visited the land of his fathers. In the autumn of 1887 he happened to read an article about the new international language and wrote in Latin to Zamenhof, who sent him the German edition of the Unua Libro . Geoghegan immediately learned the language from it. When Zamenhof sent him the English translation, Geoghegan pointed out its many shortcomings, and undertook to translate the book himself, publishing it in 1889. The German — English translation was withdrawn.

So began the Esperanto movement in Britain and Ireland. Geoghegan and Zamenhof became lifelong correspondents and friends. Geoghegan also had a hand in the adoption of the green star as the Esperanto emblem. Years later, Zamenhof wrote:

About the origin of our green star I no longer remember very well. It seems to me that Mr Geoghegan drew my attention to the colour green, and from that time I began publishing my works with a green cover. About one brochure, which I quite by chance published with a green cover, he remarked to me that this was the colour of his homeland, Ireland. Then it came into my head that we could well regard this colour as a symbol of Hope. As for the five-pointed star, it had already been adopted as representing the five continents; and so the green star was born.

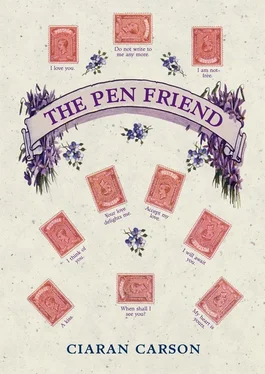

As I write to you, Nina, I have before me a postage stamp bearing that very emblem. You know I was a stamp-collector in my youth, and so, when researching the Esperanto story, I was interested to see what Esperanto-themed stamps might exist. I acquired a little collection of such stamps, issued by countries sympathetic, or once sympathetic, to Esperanto: Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland, Brazil, China, Croatia, Germany. Many of them bear an image of Zamenhof. This particular one is the Belgian commemorative of 1982, issued to coincide with the 67th World Esperanto Congress, which was held in Antwerp that year, the year that we first met. It features the smaller of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s two versions of the Tower of Babel. Above the Tower is a green shooting star bearing a rainbow-coloured tail, whose trajectory suggests it has come not from the heavens, but from Earth. And I am tempted to address this letter simply to Miranda Bowyer, Earth, and use this stamp for its delivery. But that would be wishful thinking. Instead, I affix it to this page, in the less forlorn hope that we might once more meet each other in the flesh.

As for your postcard of July 2005, it has been sent from Paris, and bears a French stamp commemorating the French statesman Alexis de Tocqueville, author of Democracy in America , who thought that association, the coming together of peoples for a common purpose, would bind America to an idea of nation larger than selfish desires. It was he who said that it is easier for the world to accept a simple lie than a complex truth. It was he who said that all those who seek to destroy the liberties of a democratic nation ought to know that war is the surest and shortest means to accomplish it. And the image on your card was made not long after the war. The caption reads

RenéeThe New Look of DiorPlace de la Concorde, Paris, August 1947

I wonder if Renée is the name of the model, or a reference to the New Look, since it means ‘reborn’ in English. Perhaps both? I look again at the New Look, Dior’s response to the austerity of wartime, an extravagant look, the soft-shouldered, slim-waisted jacket and the voluminous, exuberantly swirled skirt of the model contrasting with the almost military deportment of the three young men, whose eyes have just swivelled right to take in the gorgeous apparition.

Читать дальше