Ciaran Carson

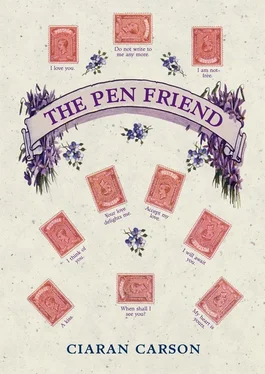

The Pen Friend

For Patricia Craig

and Jeffrey Morgan

Your postcard came like a bolt from the blue, and it was the spur that drove me to begin writing again. After my father died in 1998 — did you know he was dead? — I took early retirement from my position in the Municipal Gallery, partly to devote myself to writing a book about his involvement with Esperanto, the international auxiliary language devised by Ludwig Zamenhof. I had long been familiar with the salient details of Zamenhof’s life. He was born in 1859 in Bialystok, in the Polish district of Podlasia, once part of the Duchy of Lithuania, and then of the Russian Empire. I began studying the history of the region, hoping to gain a better understanding of what made Zamenhof Zamenhof, without which it was impossible to imagine my father. I began to discover that Poland, and hence Polish Lithuania, had been partitioned and repartitioned by a series of treaties between Prussia and Russia, behind which lay such a series of insurrections, strikes, pogroms, feuds, plots, wars, commercial enterprises and business transactions, that I realised it would take me years to unravel the particular circumstances of the town which had brought Zamenhof into being, let alone how my father had come to learn Zamenhof’s invented language.

I began to think of myself as an angler fishing a stretch of canal in the shadow of a dark semi-derelict factory leaking steam from a rusted exoskeleton of piping, who, after hours of inaction, feels his line bite, and, his excitement mounting, begins to reel in as his rod is bent by the gravity of what must be an enormous catch — a pike perhaps, glutted by its meal of barbel, perch, or one of the plump rats that scuttle through the soot-encrusted weeds of the canal banks — when to his consternation he finds he has snagged a smoothing-iron, which he discovers to be only the precursor of a series resembling an enormous charm bracelet dripping green-black beards and tendrils of slime, as the iron is followed by an iron kettle, pots and pans, a bicycle, a kitchen sink complete with taps, a pram, a harrow, a plough, forks and rakes, a gamut of broken looms, winding machines and spinning jennies, a string of dead horses, rotting straps and rusted buckles, tumbrils, wagons, engine tenders, locomotives, tanks, flat-bed trucks and howitzers, a crocodile of sunken barges, lighters, tugs, launches, cutters, gunships, battleships, amphibians and submarines sucked from the reluctant mud, the whole gargantuan juggernaut flying in midair for a second, as the angler’s rod whips back, before collapsing all about him with an almighty thunderclap; and I would wake sweating and exhausted from my nocturnal Herculean labour. My book ground to a halt before it even properly began.

I realised that even my knowledge of my father was fragmentary and incomplete. I did not know, for instance, what he looked like as a child. Cameras were not readily available when he was growing up, at least not to his milieu; and whatever studio photographs might have been taken, for his First Communion, say, or Confirmation, have not survived. The earliest photograph of him is at the age of eighteen or nineteen, when his features had been fully formed. And yet, perhaps it is possible retrospectively to build an Identikit childhood portrait where none exists.

I was reminded of this when I got your card this morning, because it occurred to me that we read handwriting as we do faces, and yours — your handwriting, I mean — had changed little, even though it was over twenty years since we had last met, and parted. Not that I believed it was yours at first; for if seeing is believing, sometimes we look and do not see; and sometimes we only see what we want to see, or what we want to believe. And now, reading your brief message for the umpteenth time — It’s been a long time , you wrote, that was all, and left it unsigned, knowing the gesture of your writing would be signature enough — I find it difficult, in retrospect, to understand my initial hesitation as to its provenance. Even when we purposely change the way we write, some ineradicable loop or slant, an identifiable arpeggio, betrays us. When we meet someone we have not seen for years, and it takes us a while to put a name to the face, we say, But you haven’t changed at all. And even when we fail to know the person, when provided with the name, we see him then, we see her then, and say, Of course, how could I not have known you? For now the evidence is unmistakeable, and we read the face like invisible writing that blooms to the surface when exposed to heat. So, even in this brief flourish I recognised the character of your handwriting; I knew its physiognomy. As you would have anticipated. The words are written in fountain pen, and in blue ink, the colour of eternity. You knew I would remember that a fountain pen had first brought us together, all those years ago.

I picture myself sitting in the old XL Café, in Fountain Street as it happens, on a Saturday in May 1982. The day before I had bought a nice 1950s jacket in the Friday Market, lightweight grey Donegal salt-and-pepper tweed with heathery flecks, little hints of purple, blue and mauve that flicker in the sunlight. I’m wearing it with a pale blue soft-collared cotton shirt and white duck trousers, so when you appear through the door in a navy check box jacket over a high-necked cream broderie anglaise blouse and a flax-coloured maxi-skirt, like Bonnie of Bonnie & Clyde, I find myself indulging in a little scenario where we go well together, such a nice-looking couple, people would say. You sit down a table away from me and order some tea and biscuits, and when they come I watch you out of the corner of my eye as you dunk a biscuit into the tea, a gesture I think at first doesn’t quite suit your style, but then I tell myself it reveals some character, it shows you’re not afraid of what people think. Against the cream blouse I notice a little pendant cylindrical jewel, some kind of étui or lipstick-holder, I think. It’s done in beautiful red and black marble swirls that show off the red highlights in your Cleopatra-cut black hair and it hangs from a lanyard that is itself beautiful, interwoven greens and reds and mauves that have the sheen of silk. You toy with it from time to time with one hand as the other manages the business of the tea and biscuits. Then you reach for it with both hands and you unclip it from the lanyard, you rummage in your handbag and take out a notebook, you unscrew the little étui, and when I see the gleam of a gold nib I realise it is a diminutive fountain pen.

You were poised to write when you caught me looking at you. You looked back. I must have blushed. Lovely pen, I said. You smiled. Yes, you said, it’s what they call a Dinkie, Conway Stewart used to make them. A lot of people comment on it, you said, I suppose it’s what you might call a conversation piece. Or lethal weapon, and you held it up briefly between thumb and four fingers like a dart. Its length was not much more than the breadth of your hand. Well, I said, I used to have a Conway Stewart, but I’ve never seen one like that. My father gave it to me, I said, I think it must have been the first fountain pen I ever had. It was a family joke of sorts, because our name is Conway, and my mother’s maiden name was Stewart. So you might say I’m a Conway-Stewart myself. Gabriel Conway, I said, and I extended my hand awkwardly across the intervening table, and you moved to take it, and we ended up sharing the empty table. You did not offer me your name at first. Oh, you said, when eventually I asked, it’s a very ordinary name, probably so ordinary you wouldn’t guess. You paused, and smiled. So what do you think I might be called? you said. Oh, I said, looking you up and down, you look like an Iris to me. You laughed. Yes, you said, Iris, of course, how did you know? I was slightly taken aback; I’d been joking, and you didn’t look at all like what I imagined an Iris to be. But I was flattered, too, that I had guessed right, and thought myself like the girl who discovers the name of Rumpelstiltskin. Iris what? I said. Iris Bowyer, you said.

Читать дальше