But of course, Nina, much of this was known to you, for when I mentioned it before our trip to Berlin in the winter of 1982, you said, Burrows? Yes, he’s a client of mine. Charming man, if you get to know him. You were wearing an unfamiliar perfume that day. What’s that? I asked. What’s what? you said. Your perfume, I said. Oh, Vol de Nuit , you said, Night Flight, by Guerlain, 1933. You offered me your wrist and I caught a burst of orange, then cool wood and balsam notes followed by an enigmatic hint of spice.

As I write to you, Nina, a surveillance helicopter is poised motionless in the sky to the east of Ophir Gardens, and the windows of my study tremble to its broadcast reverberant din. There have been many changes in Belfast since you left in 1984, though of course you might well have returned at intervals without my knowledge, and for all I know you might be in Belfast now. Your card is postmarked Paris, but that was last week. If you are here — the possibility disturbs me — you might have noticed that your old MO2 offices have been turned into penthouse apartments, and the ground floor of the building is now the Linen Warehouse Restaurant and Bar. In the side streets are cafes, gyms, aromatherapy boutiques and retro clothing stores. Belfast is booming, and not with bombs. Yet beyond the bright clatter of the lattes and Manhattans, the gleaming dishes, silverware and linen, are dark recalcitrant zones where July bonfires have been smouldering for days, and the reek of burning tyres sometimes infiltrates the inner city. Above the fragile periphery the helicopters maintain their desultory watch, scanning the ruined terraces, the blasted interfaces and the paint-bespattered Peace Walls. Every summer the Loyalist housing estate on the other side of the Cavehill Road from Ophir Gardens blooms with paramilitary regalia, flags that become tatters over the winter.

It was not always so: the estate went up in the late Seventies, built on a former allotment site which I imagine had been established during the last war, given the shortage of fresh vegetables. By the time we moved to the district in 1955, it was already semi-derelict, a few little ordered plots surviving among the encroaching brambles, nettles and chickweed, gooseberry bushes and tall rhubarb plants gone to seed, tumbledown potting-sheds overgrown by convolvulus and ivy. It was a kind of paradise for us children, where we could get pleasurably lost in war games. Later, when I read Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man , and thought myself to be James Joyce, I posed before a derelict greenhouse wearing an outfit bought in the Friday Market — a Forties jacket and waistcoat and white duck trousers that emulated his turn-of-the-century gear — and had my photograph taken by Paul Nolan, who thought himself to be Cartier-Bresson. You met Nolan once or twice: a good fellow. Like me, he took early retirement, a victim of the creeping bureaucracy that finally overwhelmed our vision of what we thought we were doing.

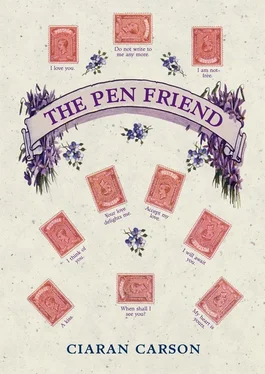

I remember telling you how the allotments had been swept away, and you said yes, your grandfather in Delft had kept an allotment, and grew cucumbers, lettuces and cabbages. Dill, too, that your grandmother would use for pickling the cucumbers. As you spoke, I thought of cool tiled pantries, and could see the tidy Dutch allotments, occupying strips of ground by the sides of roads and canals, the sheds painted in bright greens and reds, like toy houses, the rows of flowers and vegetables. I had not been to Holland then, and much of my conception of it was based on Dutch painting, which I loved, and the postcards sent to my father by his pen friend in Delft. I thought again how appropriate it was that my father should have learned Esperanto from a Dutchman, for the Netherlands seemed to me, as it did to him, a peaceable realm in which tolerance for one’s neighbours was both desirable and necessary. These were Esperantist virtues, said my father. The people of the Netherlands, he said, not having been granted much land by God, made land for themselves; but realising they could never make enough, they made space for each other. I was somewhat disappointed that Johann Wouters, like my father, was a devout Catholic, not an Orange Protestant, and that they hence had much in common to begin with. The One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Roman Church was itself a kind of Esperanto, for you could hear the same Mass in exactly the same language anywhere in the world; and when the Latin Mass, under the New Liturgy of the 1960s, was abandoned for a multitude of vernaculars, my father regretted the change. But like a good Catholic, he submitted himself to it. I think it was about the time of the New Liturgy that he threw himself even more wholeheartedly into Esperanto, as a substitute for the universality of Latin. As for me, I never properly learned Esperanto. Much as I admired it, I was uncomfortable with its dream of universal brotherhood.

Only after my father’s death did I begin to examine the history of Esperanto. I discovered that Ludwig Zamenhof had been given the Jewish name Lejzer, or Lazarus, at his circumcision, but had adopted the Christian name Ludovic, or Ludwig, in his teens, following the custom of the aspiring Jewish middle class of his milieu. Likewise, his father, a teacher of languages, had changed his name from Mordecai to Marcus. Ironically, Mordecai itself, then perceived as wholly Jewish, was once a disguise too, for in the Book of Esther it is the name of the Chief Minister of Ahasuerus, or Xerxes, the despotic king of Persia: it was the custom then of the exiled Jews to mask themselves in names familiar to their captors.

So what’s in a name, Nina? If I am Gabriel, the angel of the Annunciation, you are Miranda by another name, the admirable maiden of The Tempest . But it would also seem that names can mean anything you want them to mean, for the rabbis say that concealed in the pagan name Mordecai are the syllables for ‘pure myrrh’, and so it bears a holy perfume, an incense I remember from the Latin Masses of my childhood. I daresay Marcus Zamenhof would have been aware of this nominal labyrinth, for his own father was a noted Talmudic scholar, well used to pondering the intricacies of the Word, and Marcus himself became a teacher of languages. He also became an atheist, and in 1857 married Rozalia Zefer, the pious daughter of a Bialystok Jewish tradesman. Lazarus — Ludwig, as he would become — was the first of their eight children. Bialystok, as I mentioned in my first letter, was then in Polish Lithuania, and part of the Russian Empire. The town was a Babel. The native upper classes spoke Polish, the lower Lithuanian; a population of Yiddish-speaking Jews had long been established; there was a substantial German mercantile class; the administration and the army were Russian, and the golden domes of a Russian Orthodox church shone in the main square. The language of the Zamenhof household was mainly Russian, because Marcus believed it an essential tool to their progress. But Yiddish was also spoken, and by his teens Ludwig had also a fair command of Polish, German, and Lithuanian, as well as the Hebrew and Greek taught to him by his father. From an early age, said Ludwig Zamenhof, I was anguished that men and women everywhere looked much the same, yet spoke differently, and thought themselves to be Poles, or Russians, Germans, Jews, and so on, instead of human beings. Thinking that grown-ups were omnipotent, I resolved that, when I was grown up, I would abolish this evil; for no one, he said, can feel the misery of barriers as strongly as a ghetto Jew, and no one can feel the need for a language free from a sense of nationality as strongly as the Jew who is obliged to pray to God in a language long since dead, receives his education and upbringing in the language of a people who reject him, and has fellow-sufferers around the world with whom he cannot communicate, said Zamenhof.

Читать дальше