Nor did I see the show. There was still a mob at ENTER HERE and it was the same bunch I had seen earlier, a bit rowdier and more drunken than before. They had found a cozy place to gather and were ignoring the exhibition — plenty of time for that when the drink ran out. The party was the thing. Yet it burned me up to think that they had come here to see each other and were not paying the blindest bit of attention to my pictures.

I wondered if I should throw a fit — wave my arms and bellow at them, maybe embarrass them with a hysterical monologue about the meaning of art; or do something shocking, make a scene that they would talk about for years afterward.

Bump .

“I’m awfully sorry.” The jerk who had taken me for Lillian Hellman rushed away. The party was starting to repeat, to replay its earlier episodes in tipsy parody.

Several people, assuming my black dress to be a uniform, demanded drinks from me. They howled when they saw their mistake, but it inspired me. I found a tray of drinks and began to make my way through the room, handing them out and sort of curtseying and taking orders, saying “Sir” and “Madam” and “I’m doing the best I can.”

All my photographer friends who in other times would have been here — dead. The people I had photographed: Mr. Slaughter, Huxley, Eliot, Teets, R. G. Perdew, Lawrence, Marilyn, Harvey and Hornette — dead. Editors and journalists and gallery-owners — dead. Orlando and Phoebe: now I knew I had driven them into the sea. I had killed them with a picture. I deserved this contempt — the people shunning me or treating me like a waitress; I deserved worse — to be treated like a criminal bitch who had hounded my brother and sister to death. I put the tray down and lurked in the crowd like the murderess I was.

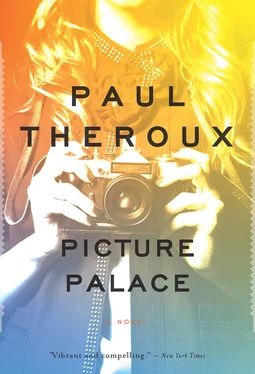

Scuffing paper underfoot I bent to pick it up, although my first thought was to leave it so that one of these partygoers would trip and break his neck. It was the catalogue, a thickish manual with my name on the front just above Frank’s and a different picture ( Negro Swimming to a Raft —but “Negro” had been changed to “Person,” making nonsense of the picture). I had refused to write the personal statement Frank had requested and had told him that I would have nothing to do with the rest of the catalogue either. I should have gone further and said that I wouldn’t be at the preview party. I felt ridiculous — guilty, stupid, ashamed — having come so far on false pretenses. I belonged in jail.

I had made a virtue of being anonymous. I had abided by it; and why not? Anonymity had done for me what a lifetime of self-promotion had done for other photographers. It was too late to reveal myself, for there was a point in obscurity beyond which exposure meant only the severest humiliation. It was better to continue anonymously and finally vanish into silence. I had spent my life in shadows as dense as those that hid me at this party. I had entered this room as a stranger — I had to leave as one. If the place had not been so impossibly crowded I would have done that very thing.

Acknowledgments , I read, opening the catalogue. There followed a list of money-machines, not only the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, but the National Endowment for the Arts and five others, including the Melvin Shohat Photographic Trust. If Frank didn’t make a go of his curatorship there was always room for such a financial genius in the International Monetary Fund.

My career, spent in attacking patronage, ended with these cash-disbursing bodies footing the bill. But I had forfeited the right to object. I was dead. They were all dancing the light fantastic on my grave.

Maude Coffin Pratt , Frank’s Preface began, is probably one of the most distinguished American photographers of our time—

“Probably”? “One of”? “Our time”? He was pulling his punches. Quite right: I had blood on my hands.

But there was, after all, a message from me, titled Statement from the Artist:

The Bible says, “In the beginning was the Word.” The Bible is in error. In the beginning was the Image. The eye knew before the mouth uttered a syllable; thought is pictorial.

Photographic truth, which I think of as the majestic echo of image, originated in the magic room known as the camera obscura . This admitted the world through a pinhole. Man learned to fix that image and photography was born with a bang. Painting never recovered from the blow. It began to belittle truth and, faking the evidence, became destructive.

One knows a bad picture immediately. All you can do with bad pictures is look at them. The good ones invite you to explore; the best drown you and keep you under until you think you will never return. But you do. I have had this experience myself.

Photography is interested solely in what is. What am I? you may ask. I can answer that question. You are a “Pratt.”

On a more personal note, I was born in 1906, in Massachusetts.

Frank’s work, the catalogue shorthand that left my life in the dark and my crime unstated.

“There he is,” said a man next to me to his lady friend. They nearly knocked me down as they moved past me.

I got behind them and followed them across the room and saw, at the center of the largest huddle of people, the Veronica Lake hairstyle, the white fretful face, the string of beads. He wore a torn denim shirt and under it a T-shirt saying It’s Only Rock and Roll ; and bright green bell-bottoms and, I knew — though I could not see them — his platform clodhoppers. He had come a long way since the day he had turned up in a barnacle-blue three-piece suit on my Grand Island piazza. “I’d be deeply grateful if you’d allow me to examine your archives.” And I had thrown the picture palace open to him.

Edging forward, I caught some of the chatter. The people surrounding Frank were talking in low voices, trying to lend sincerity to their guff by whispering it.

“It’s perfectly marvelous, Frank, every last bit of it. It’s got density, it’s got life, and it’s just about the most exciting thing I’ve seen for ages.” This from a purring pin-striped heel, obviously a foundation man.

Frank said, “I couldn’t have done it without your support. It was a long haul, but I think you’ll find that your money’s been well spent.”

“The whole committee’s here to give you a good send-off.”

“It was a risk, of course, but from my point of view”—Frank made howdying haymakers with his free hand—“Hi, Tom. Hello there, Charlie. George. Norman, good to see you. Susan, glad you could make it — a risk worth taking.”

His face’s fretfulness had a pinch of pride. He wore a tight little smile, as if he were sucking a cough drop. His eyes were vacant with self-love.

“It must have been quite a summer up there on the Cape.”

“Pretty unbelievable,” said the peckerhead. “But I feel we’ve broken new ground.”

“It’s certainly a great coup for the museum.”

Frank said, “The work was crying out to be seen. She had no idea.”

“The presentation—”

“Presentation is incredibly important,” said Frank. “I knew the minute I saw the pictures that I was on to something very big and very exciting.” Saying this, he shook his head, rattling his beads, and took a tango-step forward to plant a kiss on an admiring hag.

“Frank’s an amazing guy,” said a young man on my right.

“Don’t I know it,” I said.

“He’ll make a fortune out of this, but you’ve got to hand it to him.”

“Sure do.”

“Hassles? He’s been getting a hand-job all summer from our friend whatsit.”

“Jack Guggenheim?”

“No, um, the one who took the pictures. Pratt.”

Читать дальше