“Where’s Maude?” said the midget, looking directly at me. The woman didn’t know. They went on talking about my works of ought.

I had stiffened to prepare myself for their rushing over and saying, “Where have you been hiding?” But no one asked the question, and I would not introduce myself. I rather enjoyed my anonymity in here, as I had outside. I could mooch around, eavesdrop, examine faces and reactions, and not be required to say a single thing. Praise can only be answered with humility or thanks; I didn’t feel modest or grateful.

I was a stranger. It was the funereal feeling I had had earlier in the summer, on my return from London. But this was a joyous occasion, people saying Maude this and Maude that. I had every reason to believe that I had lived through a death by drowning. The death had shown me what I was, what I had done: it was just as well that no one recognized me.

Having entered the museum so obliquely from below I’d had to work my way up the stairs, through the throngs of people who were swigging and yelling. I had counted on seeing Frank on the landing and I winced when I gained it, expecting his shout, Here’s the star of the show! or something equally foolish. I fought forward to the exhibit’s entrance, for the party was outside the gallery proper. ENTER HERE, said a placard, but the mob I had assumed to be lining up for a look was simply gathered there blocking the way.

My impatience tired me. After fifteen minutes I was winded and wanted to sit down, or for someone — where was the peckerhead? — to rescue me. Some people stared at me and I grinned back, assuming they had recognized me. They looked away. I could not explain it, but then, I didn’t recognize any of them either.

A few years before, a place like this would have been full of people I knew — Imogen, Minor, Ed Weston, Walker, Weegee — and I searched the faces for moments before I realized that they were as dead as Mrs. Cameron. In this room was the new generation of photographers and art patrons. I could spot them: that long-legged blonde in the cape, that other ingratiating gal with the sunglasses perched on her hairdo, a pair of black simpering queens, and another black looking toothy and hostile, as if he were going to shriek at me in Swahili. Most of the photographer types were wearing leather jackets, combat boots, itchy shirts — advertising themselves as toughies, men of action. Even the gals looked the bushwhacking sort. The marauders and fuck-you-Jacks of a profession that was a magnet for neurotics, they were deluded by the fear of competition and all wearing their light meters as pendants around their necks. If it was an art, it was the only one in which the artist actually wore something that made him visibly a practitioner.

And there were others, pairs of people, slightly mismatched, whom I took to be photographers hand-in-hand with their subjects. That anorexic gal and her friend, whose face I recognized from a drugstore paperback — surely she aimed to be a credit line on his book jacket? This dapper little man and the wheezing old dame: it could only have been a relationship that started with a studio session (“Look straight at me, dear, and forget your hands for a minute”); the boogie-man and the blonde with her tough twinkle — it wasn’t too far-fetched to imagine that they had launched their romance with a camera and for all I knew kept it airborne the same way (his brutally honest chronicling of ghetto life, her cooperation amounting to human sacrifice). The bearded lout and that girl-child; the virago and her soul-mate into, as they would say, the woman’s thing. I could identify the mediocrities by their catch phrases: the prancing Minimalists, the Deeply Committed crowd, the Really Strange bunch, the Terribly Exciting ones, the Intos, the Far-outs, the Flakys.

These were cannibals’ success stories. But what the hell — they were having a swell time. Photography didn’t matter: they had each other. That was the whole purpose of taking pictures — it won you friends, it got you fame and fresh air. “I’m working on a new concept,” said the bearded lout, and I knew that if he hadn’t been a photographer in the pay of Jack Guggenheim he’d have gotten twenty years as a sex offender for some outrage upon that girl-child’s person. The work was an excuse; the idea was to involve yourself with people, which was giving photography a bad name.

My anonymity made me cynical. Perhaps I was being unfair. It was possible that they had taken pictures and developed them and, like me, at some later date, had drowned in them and known the terror of what they had done.

“He’s into some very exciting things.”

“He hasn’t had a show for years.”

“I consider this an event. He’s a very private person.”

“He’s supposed to be here somewhere.”

This “he” I kept hearing about was certainly not me. I had stopped basking. My fatigue turned complacent and then panicky. I had not introduced myself, so I was temporarily forgotten. They would be justified in thinking that I was spying on them. They might round on me and say, “At least you could have had the courtesy of telling us who you were!”

But no one in that jammed room asked.

“Isn’t that him?”

More than that (“Excuse me, lady,” a man said, yanking a tray of drinks out of my reach), I noticed a distinct irritation when my glance met one of these wild-eyed talkers, as if I were a gate-crasher who had no right to listen. I could have put up with being ignored; I could not bear being strenuously shunned. I was in the way! And there was a lot of shoving when the real celebrities showed up, various people I had seen on television talk shows, mainly hideous novelists who had written frank autobiographical books about their unnatural acts.

“Mind moving?” This from one of our photographer friends with a chunk of expensive apparatus in her mitts, a motor-driven Voigtländer aimed at my earhole.

Someone famous had just entered. Who it was, I could not say. But there was movement, a prelude to stampede, people beating their elbows to get past me.

“Pardon me.”

A man’s hand squeezed my shoulder. About time. I turned and smiled.

“Are you Lillian Hellman by any chance?” The man bowed to hear my reply.

“Sorry, buster. I’m her mother.”

But though I was furious for being mistaken for Lily (is there any old lady on earth who is flattered by the suggestion that she resembles another old lady?), I hoped the man would pause long enough for me to tell him who I really was. Rebuffed, he fled sideways into the mob.

Already I was sick of the party. The people had stopped talking about me and on their third or fourth drink were just whooping it up, paying no attention to the posters with my name on them.

“He’s done it as a multi-media event. I’m going in as soon as they shut this wine off.”

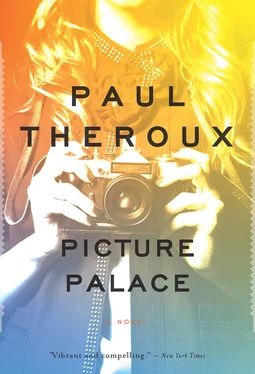

I had no business here. This was a spectacle of the kind I had avoided for thirty years. There was no reason why anyone should have recognized my face: professionally I had no face. I was for most only a name and Twenty-two White Horses and celebrated for a period of blindness when I had done Firebug . For one person I was the Cuba pictures, for another the Pig Dinner sequence; blacks knew me as the creater of Boogie-Men , New Englanders for The South Yarmouth Madonna , Californians knew only my Hollywood work, the British were aware of my London phase but nothing more, literary people my Faces of Fiction , and for some camera buffs I was the young gal who had done Stieglitz with his own peepstones.

To be famous is to be fixed — a picture, a date, an event, a specific and singular effort. To be fixed is to be dead, and so fame is a version of obscurity. One appeared at one’s own party only to haunt it. If Frank had been around he would have steered me into the crowd and made the usual introductions, as the custodian of my reputation. But I did not see him.

Читать дальше