journalistic scrupulousness

The moon over everything an appropriate lighting. I’ve bent Svensson’s paper clips and tried his pens, I’ve searched for the key to the suitcase, I’ve pulled and tugged. Without success. My kneeling in front of the suitcase, Tuuli’s golden hairpin in my hand, the window is wide open: Macumba in the water and the lights on the other side of the lake. Do I hear footsteps on the stairs? Do I hear Tuuli singing? Is Svensson still talking? Tuuli’s hairpin is slightly curved and rounded on one end, it’s sturdy enough to turn in the lock, and Svensson’s suitcase (Blaumeiser’s suitcase) acquiesces, it opens with a soft click, and that very second all the lights turn on in the room.

That a night can suddenly be so bright.

That a dog can die so loudly.

Quiet, Lua, quiet!

My wincing and springing to my feet and standing paralyzed: I’m frozen in front of the open suitcase in the brightly lit room, the dying dog by the water is coughing and barking at the same time, down below Svensson is emerging from the house (two tinted lights at the end of the dock, a floodlight with a motion detector on the outside of the house). Tuuli follows him and talks relentlessly at him: it was a fuse, idiootti , she only had to flip the switch! Not Claasen, not a power outage, not fallen trees, not heroic independence, not rebelliously refused bill payments, not his retreat from this world, paskapää , only his morbid collection of old, useless things, his dumb insistence on a corny idea of the ruin, only his inability to deal with the present. Only a damn fuse (a bogus epiphany)! Then Lua is finally quiet.

in the suitcase

Stones (heavy), flowers (dried), finally: a thick packet, brown paper and tight packing string. I put the packet on the desk (that smell of old suitcases), untie the knots very carefully and remove the paper (journalistic scrupulousness). That a night can be so quiet (that paper can rustle so loudly). I find the light switch and turn off the lamps.

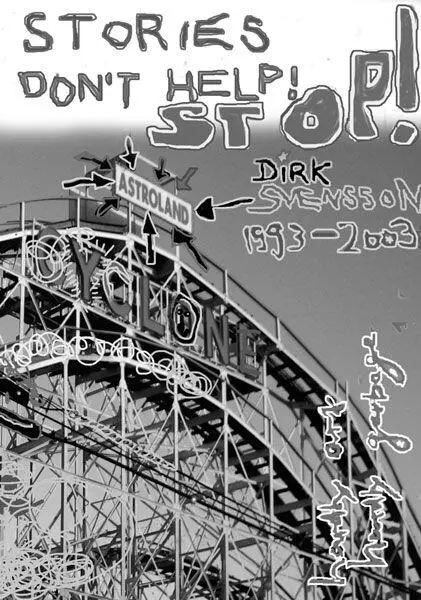

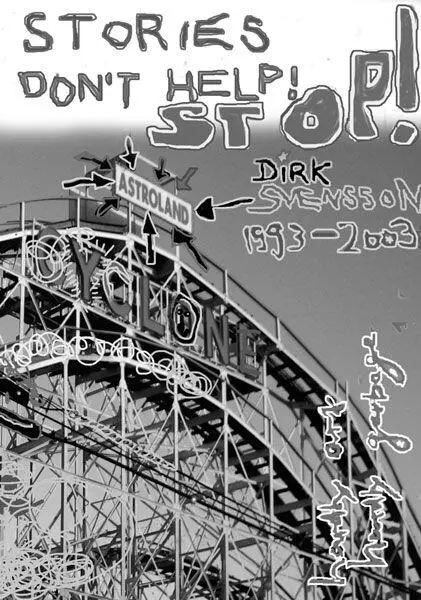

Astroland

Observed from the safe darkness of the room: on the way to the lake Svensson takes off his T-shirt, he leaves his shoes in the grass and tosses his pants aside, Tuuli picks them up and throws them at him furiously (can that be explained?). In the light of the motion detector, Svensson finally stands naked on the dock. For a moment he looks across to the opposite shore, then for a few seconds at Tuuli. She’s still berating him, but I don’t understand what she’s saying. Svensson spreads his arms and dives headfirst and perfectly straight into the black lake (reflection of the sky). The water splashes up over him, the surface evens out, Tuuli is standing alone on the dock. On the other side of the lake shines the yellow tower of Santuario di Nostra Signora della Caravina, in the deeper water is the white buoy, above the lake Monte Cecchi, the moon. Svensson has vanished (everyone is waiting). Svensson doesn’t reappear. The light over the property goes out, because no one is moving.

Svensson can’t lose.

In the unwrapped packing paper in front of me the thick stack of paper:

Capoeira with Heckler & Koch

MY BAG IN THE BACK OF THE TRUCK, THE ANTARCTICA BOTTLES open, and we’re off. David at the wheel of the red pickup, Felix in an open shirt and panama hat, me with the twenty-four-hour flight in my bones. We blast through a red light. Between the entrance ramps and concrete pillars the greenery grows rampant, and over everything an airplane thunders in for a landing. Felix reaches for the glove compartment and tears the door off, holy Mother of God, there’s nothing there, did you drink it all, he asks. David? And again: David? Felix says “DAVI” with the last d silent, as Brazilians do. David with his pitch-black skin drives with tunnel vision down the street, a luminous tube through the sultry night, from the rearview mirror dangles a crucifix. Synthetic lambskin hangs over the seats. At our backs shimmers the Recife airport. Felix raises his bottle, spraying some beer, welcome to the tropics, my Svensson! Felix is wearing multicolored bracelets around his wrists and explains that that’s what’s done here. I’m out of it, in the glow of the streetlights before my eyes there’s a sprinkling of moisture or cigarette smoke. Or is it the light-emitting diodes in the crown of the holy Madonna flashing from the dashboard? Is the driver really wearing the black skull-and-crossbones sweatshirt of FC St. Pauli? I say: The flight from São Paulo was a disaster, they’d unscrewed the seats next to me, there were only two other passengers on board, the propellers were flapping and grating. There was beans-and-rice and nothing to drink, it was hard for me to swallow. Felix and David raise their bottles with a loud clink. Turn on the music, meu amigo , says Felix, make it louder, there’s something to celebrate, Svensson’s here! I say: I guess I am, but where are we actually going?

The pickup roars along the Recife beach promenade, the left rear wheel suspension makes a whistling sound, or maybe it’s Felix singing to the music on the radio, “Girl from Mars.” Now and then a streetlight, now and then none. On the left the black sea and the white streaks of the waves, on the right beach bars with strings of lights or strings of lights on wooden trellises over the doors or over a few men in open shirts, over beer bottles and card tricks. And the waves crash on the beach. Then steel fences, behind the steel fences high-rises, between them dark green bushes with thick, shiny leaves, Madonnas with low-voltage aureoles, now and then a neon cross, soldiers and armored cars and rifle barrels on the driveways. I ask: Are those Kalashnikovs? No, answers David, all Heckler & Koch, quality workmanship from Germany! Then the pickup leaves Boa Viagem, first come flat buildings made of concrete, then corrugated iron, then plywood, then cardboard. Felix opens another bottle of beer and pushes his hat back, I say: From above the city is a carpet of glowworms and frayed at the edges. Tourist, hails Felix, those are the fires, there are no glowworms here, this here is the favela of Recife, Svensson, you understand? I don’t understand anything, but meanwhile I’m holding in my hand my third beer since my arrival in Brazil. David turns the corner and winds through the muddy roads, he avoids the cardboard huts and burning garbage cans, the dark faces between the flames, and they all turn with the pickup like flowers with the sun. I ask again: Where are we actually going? The pickup stops in front of a poorly lit shell of a house, on the second floor a few windows are illuminated, in front of the house a tin garbage can is burning and throwing off sparks. Here, says Felix, to buy weed. I ask: Can’t we just get a beer and then go to a hotel? Don’t worry, my Svensson, says Felix, jumping out of the truck, this is all great fun.

I ask through the open window: Isn’t this dangerous? Felix hunches his shoulders as he walks toward the mossy ruin. I get out and follow him, I ask louder: Isn’t this dangerous? Toward the horizon the lights of a tanker or an airplane in descent or the sparks over the garbage can? I say, Felix? But Felix is climbing the dark staircase, stepping over the trash on the staircase, he jumps over a man lying in a watery pool on the concrete, the man is snoring and stinks. Felix? Be quiet, Felix replies, or else they’ll hear your fear, and I can’t say they’re harmless. Up above, light falls through a door into the stink of piss and onto the stains on the walls. Am I breathing too deeply? Can fear be heard? In here, says Felix, and I think: Get out of here! and stay in the stairwell. I hear terse sentences from inside, and someone laughs loudly. I turn around and begin to go carefully down the stairs. Is the man on the landing snoring louder as I step over him? Are the fluorescent lights in the stairwell flickering or am I not seeing straight? Is that piss or liquor or mildew burning in my eyes? Am I sweating going downstairs in the dark? Is that possible? Can all this be true?

Читать дальше