M: My wife loves Barolo.

S: You’re married?

M: For two years.

S: I’m not.

M: But it’s not that I regard marriage as the only true life plan.

S: What?

M: Sorry. Do you live completely alone here?

S: I’m not lonely.

M: Did you write and illustrate your book here?

S: The glasses are up there in the cabinet.

M: The pictures in your book, are they…

S: Yes?

M: In the seclusion of this house, do you even take notice of the success of your book?

S: I don’t read newspapers, Mandelkern, I don’t own a television.

M: You live alone with Lua? An unusual constellation for a children’s book author.

S: What?

M: I just mean — if I may — that such reclusiveness is somewhat unusual. For a children’s book author. What one imagines when one thinks of a children’s book author. And Lua is no ordinary dog, if I may say so.

S: Lua and I get along with each other.

M: How old is Lua actually?

S: I don’t know, Mandelkern, German shepherds sometimes live to be fifteen years old. Lua is older, Lua is a memory animal.

M: How long have you had him?

S: Lua was already here long before us, Mandelkern. He was Claasen’s watchdog, his pack animal, he pulled his children’s sled in winter and the wagon in summer, he has barked from San Salvatore and from Monte Cecchi, he has howled at Napoleon’s Iron Crown of Lombardy, he has bitten the Habsburgs and peed on Mussolini’s leg, he has slept under Klingsor’s balcony and brought Herr Geiser over the mountain. But those are other stories.

M: Herr Geiser?

S: Mandelkern! You’re supposed to be a cultural journalist!

M: And Lua’s leg?

S: I’ve never seen his leg.

M: But yesterday you said…

S: Let’s drink, Mandelkern, the wine’s been breathing long enough. Chin-chin!

M: To Lua.

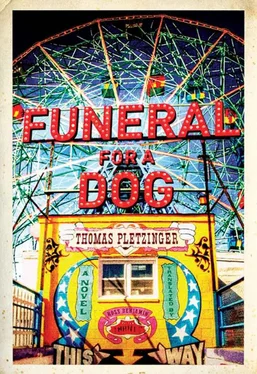

S: To Felix Blaumeiser.

To the old days!

he says, but Tuuli doesn’t respond. She drinks without looking at Svensson and stubs out her cigarette in the sink (her wet hair combed back). Then the heavy pan and the fragrant fish between us (the eyes now murky), we eat without a word, only the boy asks sporadic questions and gets selective answers. (Why’s it called a one-eyed Jack? Do dogs like cold fish?) Tuuli cuts an apple for him, later the boy climbs from his chair onto his mother’s lap, lays his head on her chest, and closes his eyes (words fail me). Tuuli enfolds him in her arms and hums the Finnish song that I heard through the wall last night, she removes his shoes and holds his little feet, she herself eats with her left hand (their shared calm, my unexpected emotion). The fish is perfect, the wine a little too warm (Elisabeth would send it back). Svensson and I listen to Tuuli’s singing until our plates are empty too, until the boy has fallen asleep, then Svensson gets up and strokes the sleeping child in Tuuli’s arms on the cheek. He could teach the boy how to fish, he says, pointing to the yellow fishing rod, which is leaning, still in its plastic, in the corner of the room.

the demotion of the Fiat

Svensson rekindles the light. Tuuli has brought the boy into the room next to mine and left the door wide open, I wash the plates as if I belonged here. Tuuli is watching me as she smokes my cigarettes (Muratti 2000). These candles, says Svensson, are the last light of the day. He speaks with proud enthusiasm of his house, of the chickens and dogs and chairs, of the view of the opposite shore, he tells about Claasen and Claasen’s wife and Claasen’s sorrow, he talks about the seasons and fishing grounds and plant cycles, about the access road that’s been overgrown for years (the extension of the Via San Rocco into nothingness). He laughs about the demotion of the Fiat from small car to a pen for small animals. Svensson is a feverish storyteller, his stories intertwine, his punch lines flare up in unexpected places, our glasses clink (even Tuuli smiles occasionally). I enjoy listening to Svensson, and he seems to have been waiting for listeners. He pours wine into each of our glasses, he speaks of the local birds and trees and water snakes, there are vipers here too, he says, raising his glass with every joke and then at every sad turn (I’ve given up resistance). If the boy wouldn’t wake up, if the candles wouldn’t burn down, if the next day wouldn’t come, if I didn’t have 3,000 words to write, if Tuuli didn’t have to sleep too (a gap in her teeth when she laughs) — we could sit here forever, I think, why not? But Tuuli downs her glass in one swig and Svensson gets up. He asks for a cigarette, then he leaves. Tuuli refills the boy’s juice glass and pushes it across the table to me ( succo di mele ). Let’s conclude the evening by drinking something sensible, Manteli , she says, or else tomorrow will be a disaster.

apple juice

With a little patience and spit, said Elisabeth, standing up. The digits of the alarm clock at 2:17 AM, down below on Bismarckstrasse the scrape of a bicycle and a mosquito in the room, the summer settled on the roofs. Elisabeth is not a squeamish woman (at first she’d remained dry). I noticed that I was intensely thirsty and Elisabeth’s eventual wetness on my cock was long dry (my own sticky wetness). I first heard the toilet flushing and then the opening and closing of the fridge, Elisabeth was singing “In My Solitude.” Then her singing stopped (it felt as if she were dead). When she returned to the mattress, she pushed me back and kissed me with open lips, from her mouth cold apple juice flowed into me (Elisabeth the woman I’d been waiting for).

Interview (anniversary of a death)

MANDELKERN: So are you a doctor?

TUULI: I’m drunk.

M: What kind of doctor?

T: Surgery. In the Charité.

M: I once read that surgeons are the artisans of the field. Is that true?

T: I’m not a psychologist, I amputate.

M: Really?

T: Yes, Manteli , Lua’s leg was the first body part I cut off. Otherwise Lua wouldn’t be alive today, he would have bled to death ten years ago.

M: I thought Lua had always been here on the lake.

T: Poppycock. Did he tell you that?

M: He did.

T: Svensson changes stories the way other people change shirts. He’s always done that.

M: You’re very young for a doctor.

T: I started early, Manteli , I’m old enough. For surgery and cigarettes, for everything.

M: I’m smoking again too.

T: We’re all going to die.

M: No one said anything about death.

T: I want to tell you something, Manteli: Tänään on se päivä kun hän kuoli .

M: Today is the anniversary of a death?

T: Today death is everywhere. Everything here in Svensson’s house is stories and death. Just take a good look around. The silverware is old, the pictures are of dead animals, the dog will die soon, the access road is overgrown, the chairs are rotten, the house is a ruin. This lake is a grave, and Svensson is sitting on the edge. I can hardly bear it, Manteli . Svensson collects the past so time won’t disappear, so each day isn’t one more day that Felix Blaumeiser is dead, so life won’t go on without him.

M: The anniversary of Felix Blaumeiser’s death?

T: Do you speak Finnish, Manteli ?

a match breaks

Tuuli’s hand then suddenly on my chest, our cigarette in her other one. With this beauty rising toward me I miss the sound of the sliding door and the footsteps on the stairs, but Tuuli jumps back decisively just in time and laughs a mocking “ Idiootti ” into the room (she doesn’t mean me). Svensson is standing in the doorway, to celebrate the occasion, he repeats, showing us the gin bottle in his hand (a somewhat too-long pause), to celebrate this special occasion,

Читать дальше