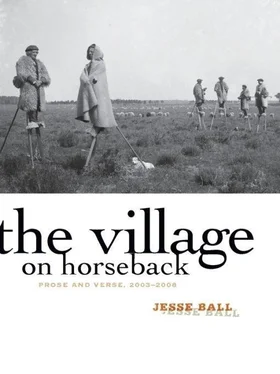

Jesse Ball - The Village on Horseback - Prose and Verse, 2003-2008

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jesse Ball - The Village on Horseback - Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Milkweed Editions, Жанр: Современная проза, Поэзия, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008

- Автор:

- Издательство:Milkweed Editions

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Samedi the Deafness

The Way Through Doors,

New Yorker’s

The Village on Horseback

The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Lubeck’s folks smiled encouragingly at Carr as he went away in the clothes of their murdered son.

Then the dream shuddered, and he woke.

He was lying in bed, in his room. He went to the window and opened it. It was dark out. He’d slept the whole afternoon. The dream was muddled in his head, and sat with unconscionable weight. What was true?

He thought and thought.

The Judge’s wife, he thought. She didn’t come here. Then it was on him again. There was no lie. There had been a miscarriage. He sank to the ground beside the window, and sat back, curled against the wall. They were guilty. They had done it.

There was a knock at the door.

Carr went towards the knocking. Lubeck’s stepfather was standing in the corridor.

— Thought we’d check on you. Everything all right?

Carr shook his head.

— Tomorrow, eh?

Carr indicated that the man should come in.

— No, no, I’m not staying. Just stopped by for a moment.

A thought struck Carr:

— What is the Judge’s house like? Have you ever seen it?

— It’s a small place, near the mill. A stand of birch trees, and a red house left of the curve.

I know it, said Carr. So that’s the house. It’s a small house.

— Yes, said Lubeck’s stepfather. A small house. Are you going there?

— Not me.

Carr related the events of the morning.

— So, tomorrow. The track?

— I am, said Carr. I don’t see a way out.

— I’ll go with you, said Lubeck’s stepfather.

— You don’t have to.

— I know I don’t have to.

— All right.

— Tomorrow then, I’ll come here.

— Tomorrow.

Carr shut the door. The dream had now gone from him completely. He could no longer remember having felt betrayed by the Judge and his wife. His anger at the Judge was vanished in every extremity. In every direction, he could see only what they had done, he, Brennan, Lubeck and Harp, and how it could not be fixed.

No one explains this to you, he thought. That there are so many things without solution.

He lay down again, and lay for some time, with a blankness in his eyes before sleep drew him on like an illshaped coat.

Another dream, and Carr found himself sitting on the lawn of a great, landed estate. He could not turn around. He did not know why. Behind him, someone was speaking. A man was speaking about the construction of a cemetery, of black granite, of the need for the services of a particular sort of stone mason, of the rationale for certain wind direction and distance from the sea. Carr drifted deeper into sleep, and was gone even from his own dream.

the eighth

He lay in bed. He could smell the morning where it was around him. A dog was barking somewhere in the building. A wind was blowing, and the house creaked. Doors locked shut strained to be wall, but they might never be. In a moment he had risen and passed out of the room. He did not permit himself to look at it before he left.

Carr was early. He was outside. It was cold. It was early to have gone outside. There were trees that lined the street. Each had been allotted an area of stoned-in earth. More than a hundred years ago, it must have been, for now the trees’ roots up and down the avenue stretched and crouched and broke at the surrounding stone. The trees rose to make a tunnel of the street in summer. In winter the fingers met in the air all along, winding about each other. He felt the permanence of the street, of the town, the permanence of the trees. The wind came up again and turned him, pushed him a half step. He looked away from the wind. The sky was brightening. The wind blew harder and harder. He turned up his collar and sheltered against the house.

When he looked back, the automobile was waiting. He got in.

Lubeck’s stepfather squinted when he looked at him, put the car in gear and pulled out into the road.

Carr looked down at his clothing. He was wearing his best, a three-piece suit, an overcoat. Why? He himself could not say.

The car wound here and there. Lubeck’s stepfather was taking a different route. Somehow this was a vague hope. He had never thought of driving in a different way to the track. Might that change things?

But soon enough, the ways came together, and it was over the bridge, through the curling country, and then up ahead, they saw, distinctly, through the starkness, a car and two figures waiting.

Lubeck’s stepfather pulled to the side of the road.

— I’m sorry, Leon, he said. I can’t stay.

Carr nodded. He patted the man’s shoulder and got out. He could see through the trees the Judge’s profile. The second figure was a woman.

Up to them went Carr.

He nodded to the Judge. He looked then clearly on the Judge’s wife. She did not look very much like she had in his dream. This woman had clearly been quite ill. What must it have been like? he wondered.

— I’m sorry.

The cloth was laid on the hood. The pistols were there.

The Judge had turned away. He was staring off into the trees.

Carr touched his shoulder.

— I want to say, said Carr. I want to say I’m sorry to you both. We didn’t know what we were doing. It’s strange how luck can be so large and small. One turn, and everything goes. I mean. .

The Judge looked at him wordlessly. The Judge’s wife’s face was drawn and pale. Her hand twitched.

Carr continued.

— I don’t know what this is for you, what your life was, what it would have been. But this, it was something that happened in a street. There are streets and things that happen in them, and no one knows how or why. I want, I mean. .

He looked around him. The day was now come completely and the track stretched away. The trees rose up. The drive curved into the road which ran on and on into the town that he knew, and beyond. Birds sailed effortlessly between cold branches.

— I mean, he said. I mean. .

The Judge’s wife moved. She put her hand on the Judge’s arm.

— Allen, she said. It’s time. Let’s be done with it.

He turned towards her, and his back was to Carr. Her eyes came over the Judge’s shoulder. They were dark and small. There was nothing in them, nothing at all.

— Love, said the Judge quietly, he stopped the other yesterday. Hasn’t it been enough?

Carr could not hear her reply, but the Judge spoke again, and then she spoke. She spoke on and on, her voice rising. The Judge turned back then, and his face was grieving.

— Take one, he said. Take a gun. Let’s be done with it.

Carr took the pistol closest to him. It felt strange in his hands, smooth and heavy.

The Judge took the other revolver and went out onto the track. Carr followed.

The lines were still there where they had been drawn. A sickness was in Carr’s belly. He felt himself thin and weak. He was walking and he was not. He felt that he was watching himself walk to where he would begin.

The Judge was where he would be. Carr heard the Judge’s wife call out the signal.

Then they were walking towards each other. Carr held the pistol out in front of him. He pointed it like a stick and pulled at it with his fingers. He pulled with all his fingers and it went off. It went off again. The Judge was still there. They were at the lines. The Judge fired. He fired again. Carr felt his chest was hurting. He felt his legs hurt. He was firing, and the air was very clear. There was a hole in his chest. He could see it there. When had it happened? This was another thing that could not be fixed. Panic and his face white, and he was on the ground with his hands.

He could not see the Judge. He could not see the Judge’s wife. The cinders of the track were in his hair. He could feel the track beneath him, and stretching out in every direction above there was a depth to the clouds that seemed very far and good. But then he saw that it was shallow.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Village on Horseback: Prose and Verse, 2003-2008» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.