— Of course, said Corina. But I don’t like to speak of it.

— You have memorized every inch of Plutarch’s Lives, and you have long imagined that it would be a splendid thing to illustrate the staircase with those splendid books in Greek script stretching the whole way. However, you haven’t the proper brushes or ink to do the job and so it has gone undone.

— Well, I never, said Corina. You are something else.

— I could get brushes and ink for you, said Kleb. You should have said something before.

— All right, said Corina. I would like that very much.

— I was thinking, said the municipal inspector, about writing a book in which whenever a character lies, his or her dialogue is in italics. You would think at first that that might simplify things, but I bet in the end, it would only really complicate them.

— Well, said Morris, who was eating a big piece of buttered corn bread. If it was a detective novel, you would see that someone was lying when that person was talking to the police and then you might think that person was the one who did the murder, but really, everyone lies and maybe the murderer goes through the whole book without telling a single lie. He might just be good at avoiding having to lie. But the readers would be misled into thinking he was not the murderer, just because he seems to tell the truth.

— Yes, said the municipal inspector, thus the business of subterfuge.

Three moments later it was evening. The table had been cleared, the visitors had been shown where they would sleep, and then Kleb had taken the municipal inspector out to the field where the horses graze to sit upon a hill and talk. The guess artist remained with Corina, who was in the midst of baking a sort of sausage bread that the two would take with them on the morrow.

Selah sat on the hill’s crest. Kleb sat beside him and placed between his own two feet the unlit lantern. The last light came from the mirrored vents, and darkness descended.

— I don’t mean to be rude, said Selah. But we are in a bit of a hurry. We’re looking for a girl named Mora Klein. I need to get upstairs, but it seemed like going downstairs was the right way. At least, someone told us so.

Kleb thought about that for a minute.

— I don’t know exactly what you mean, he said. But perhaps after I’ve explained about what I’m set on explaining, it’ll have helped?

— I hope so, said Selah.

— It was a long time ago, said Kleb, that a man named Norburn was digging a well on his property. The year was 1863. The Civil War was on. People were angry. Mobs rioted in the streets. But Norburn began to dig a well. Everyone told him that it was idiotic to try to dig a well through the bedrock in Manhattan, and yet he persevered. Norburn dug down seventy-five feet, which was an extraordinary depth for the time. The digging of the well killed him, for he attempted it in summer, and the heat was too much. He never found water. However, his son, also named Norburn, continued the work. At ninety feet, Norburn struck not water, but an empty passage. The rock fell out beneath him, and he was left clinging to the side of the well. Luckily, there was a rope ladder that he had been using in the first place to get in and out. He climbed back up, fetched a longer rope ladder, and descended. But this got him no farther, for the darkness below was immense, and the space into which he had channeled was huge. He made rope ladder after rope ladder and strung them together, but as far down as he went, the hole went still farther. Finally, his making of ladders, and the business of this well (which was concealed now within a small shelter so that the neighbors would not suspect any strange business) attracted the attention of a federal agent, a man by the name of Bascomb Lefferts.

— How did he find out about it? asked Selah.

— That I don’t know, said Kleb, but find out about it he did. Lefferts was a man of some learning, and of great acuity. He saw immediately that there was something here that needed the highest degree of caution. He would brook no interference from local authorities, and so, after examining the hole and descending as far as was possible (a herculean task, since it involved first gaining the strength of arm to pull oneself up and down a several-hundred-foot rope ladder), he set out for Washington. Now, as we have said, the war had been going on some time. Washington was an armed fortress, and Lincoln’s ear was not easy to get. Yet Lefferts had a certain reputation himself, and one day he was put into Lincoln’s company.

— Sir, he said. Might we speak alone?

Lincoln gestured that the many strange and impetuous avatars and incarnations that accompanied him in the form of bespectacled clerks should be off for a moment about some putative business. They left Lincoln and Lefferts in a pronounced globe of quiet.

— Speak, said Lincoln.

Then Lefferts explained to the great man what it was that he had found. He explained that he had dropped enormous rocks down into the hole, and that no sound had ever been returned up out of it. He explained that one could scale down into the hole for hundreds of feet and be no nearer the bottom. He explained also that lamps lit and dropped also disappeared from sight.

Lincoln then set Bascomb Lefferts at the head of a special task force. He commissioned him with the finding of the bottom of the hole, using any means necessary.

— This may be a godsend in pitiful disguise, he said.

Lefferts never forgot that. He had the phrase engraved on a small metal plaque, and wore the plaque about his wrist as a constant reminder of his mission. Over the next two years he worked day and night, building rope ladders and lowering himself deeper and still deeper into the hole. So long did the rope ladders become that he began to build hammocks that would accompany the rope ladder in order to provide rest for the tired climber. Finally he despaired even of this, and he had a huge cable made, such as was used to bind clipper ships to trading docks. To the end of this he attached the basket from a balloon. He had a massive winch set inside the now formidable enclosure that surrounded Six Quince Street, and down into the hole he had himself lowered, lanterns in tow.

The winch ran out of rope four times, and had to be restrung. Each time the rope was separated, tied off, then strung together with the new rope and lowered. Finally Lefferts reached the bottom, where we now stand.

At that time it was only bare stone, a wide cavern of bare stone, with a stream running through it.

Lefferts cried with joy and laid himself down upon the cavern floor and spoke once more the words that Lincoln had said: This may be a godsend in pitiful disguise.

However, the disguise was no longer pitiful.

Lefferts had himself winched back up out of the hole, and he went immediately again to Washington. He sat with Lincoln and told him all that he had found. Said Lincoln:

— I have thought often of your hole, and of what might lie at the bottom. I am best pleased by this that you have found. Here are my plans for what should be done.

Lincoln had set up a special government branch, sealed from the rest and with only this single purpose in mind: to build a passage down through the hole, and place at the bottom a replica of a meadow and cottage that he had seen once in a dream.

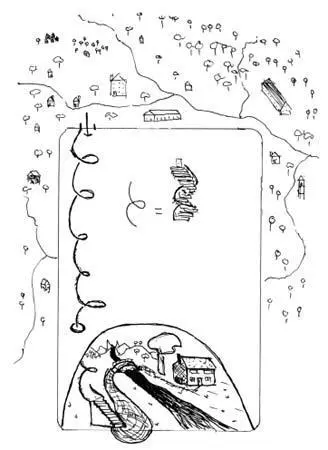

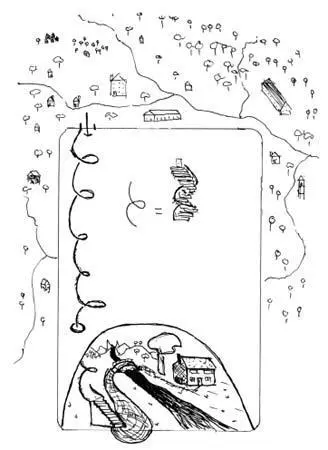

This was the plan that Lincoln had drawn:

Lefferts returned, now flush with cash, and began the work in earnest. He had to keep the proceedings secret, and so the entire area had to be sealed. A large building was built over the hole, and the work went on underneath, done by workers whose children were kept as hostages in a separate federal camp near the Canadian border.

Читать дальше