— Today you are to marry the man whom I once loved. Do you know this?

Still the other says nothing.

— I am giving to you possibly the most remarkable man that was ever born and raised in this our land of Russia. He is a king among men. His tastes are the most refined tastes, his passions the most refined passions. I am giving him to you, forcing you upon him, because I know how horrible it will be for him who was once raised above all other men to taste the wares of a creature as despicable as you. What do you have to say to that?

To that, the ugly woman continues to say nothing, and the queen goes away. The light pouring through the window has the sheen of new light, of early light bred away in the east and brought here with a spring in its step. It dances through the window, coming in turn upon the face of the wretched woman and the queen, and delighting in both.

And there in the dawn, the ugly woman smiles.

— Still I will make him happy. Ugly as I am, I will please him, if he is so great a man.

The film reel blurs for a second. It is in black-and-white, and very grainy. The guard is speaking. His voice is distorted.

— There is someone to see you, Kolya.

— Thank you, she answers. I would like that.

Then a young woman enters the room, dressed in a sort of flapper outfit. She sits down beside Kolya and takes her hands into her own.

— THAT’S HER! shouts Selah and jumps to his feet. MORA KLEIN!

— I thought it might be, says Levkin quietly.

— This is how things are going to proceed, says Mora Klein to Kolya.

And bending, she whispers something into Kolya’s ear. The film ends, and behind Selah the reel flaps against the projector.

— It was her, he says again. But how?

— We are not certain, says Levkin, of whether that is: a. actual footage taken from the memory of someone who has not been delivered of the facts of their past life, b. a film shot in the 1950s, or c. a postulation on the part of a cruel and uncertain fate.

— I don’t entirely understand, says Selah. What do you mean?

— Well, says Levkin. Your girl, Mora. She might have been in the event in question. Or she may have been in the original historical occurrence. Therefore, should this prove a filmed reconstruction of the historical occurrence, they would then have had someone playing her with greater or lesser skill. Perhaps enough skill to fool you into thinking you are watching her.

— But, says Selah.

— Or, continues Levkin, she somehow managed to be present both in the historical scene and in its reconstruction and subsequent filming.

— I begin to see, says Selah. I will have to think about this.

Both men stand and look at each other in the darkened room.

— So you’ve been working on pamphlets? asks Levkin.

— I’ve finished it, says Selah.

— What have you finished?

— World’s Fair 7 June 1978. It is my precondition, set at the start of the world.

— Very good, says Levkin. I will have to look at it. I thought, he says, that I saw someone a few days ago carrying a copy. I tried to look closer, but she noticed me watching and hurried away.

— Sif, says Selah. A girl. She came to the apartment of the pamphleteer.

— The pamphleteer? asks Levkin.

— The pamphleteer, replies Selah.

Levkin nods in a Levkin-like-Wednesday-way. Selah continues.

— Selah, she said, I want very much to read your WORLD’S FAIR and I am not about to wait any longer. She was wearing a short dress with very spectacular Roman legionnaire sandals that strap all the way up to the knee.

The pamphleteer had just come from a bath and was wearing a flannel nightshirt.

— How did you get in? he asked.

— Your keys, she said, holding them up.

— I never gave you my keys.

— But I spoke to your super and had copies made. I thought it would be prudent. I knew there would be a time when I would want to enter your apartment without your permission, and now that time has come. Give me the WORLD’S FAIR.

— But it’s not done, he said.

— It will never be done, said Sif.

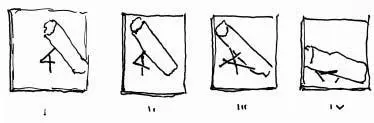

She came closer and grabbed his ear. The gesture was very rapidly done, and it flashed in the pamphleteer’s head that he would like very much to draw a schematic of the action and put it in the World’s Fair 7 June 1978, along with vector lines of force and angles of incidence, etc.

— Here’s the story, she said. I’m more stubborn than you are. I’m telling you now I won’t let go of your ear until you let me read WORLD’S FAIR.

She gave him then her winningest smile.

The pamphleteer smiled too.

— You know, he said, I was thinking of taking all the smiling out of W.F. In Seymour, an Introduction, he goes on about how smiling is just awful and no one should do it, in books, at least. What do you think?

— Smiling is for the birds, said Sif. Now give me the goddamned book.

— All right, said the pamphleteer. I’ll give you an early version. But hold on a moment, because I have to add one more bit.

He walked over to his drafting table. On the butcher paper he quickly sketched out the schematic he had just imagined, complete with a figure indicating Sif and a figure indicating himself.

Sif (still holding on to the pamphleteer’s ear), said,

— Do I really look like that?

— Much cuter, he said. And craftier-looking.

— Do I look crafty? she asked.

— You’re just the craftiest, said the pamphleteer.

This pleased Sif immediately. The pamphleteer rose and crossed the room, Sif hanging on all the while. He proceeded to make a lithograph plate of his schematic. This took some time.

— Can I get a drink? asked Sif. I’m very thirsty.

— All right, just give me a second, said the pamphleteer. He put the plate into the lithograph machine, put some good-quality paper underneath, and made a print. Taking it out, he smiled.

— Not bad, said Sif. Now, to the refrigerator.

They crossed the apartment. Sif took a bottle of iced tea out of the refrigerator. She poured two glasses and returned it. Lifting the glass to her lips, she took a long sip.

With a spluttering laugh, she shook her head and put the glass down.

— Not an American cabernet, she said, an Italian, even a Chilean. American cabernets are fine. But not for this….

She shook her head again.

— You really don’t have the right instincts for this business of putting iced tea into old wine bottles.

— Fine, said the pamphleteer, blushing. Let’s finish this so you can let go of my goddamned ear.

Together they managed a sort of three-legged race over to the printing press. The pamphleteer took a little box from off the top of a pile of little boxes. On the cover it said,

WF 7 J 1978

Out of the box he slid a thick pamphlet. He took the printed schematic sheet and, taking a sewing needle and some thread from off a table, sewed it into the pamphlet. Then, turning, he returned the pamphlet to its box, kissed it once upon its cover, and presented it to Sif.

— For you, he said. You’ll be the first to see it.

Sif let go of his ear and did a little dance.

— I’m so happy, she said. This had better be good. You’ve refused countless outings with a certain girl named Sif on account of you were working on an important book. SO it had better be good.

She threw her arms around his neck and kissed him. Then she danced off to the door. She pulled her bag off a hook on the wall, slipped W.F. into it, and herself slipped out the door.

Читать дальше