I said, Emmanuel, I’m ten years old.

He said, “And you’re the only one who thinks that makes a difference, Gurion.”

The only one? I said. I said, There’s millions of Israelites who don’t even know who I am, let alone—

“There are millions of Israelites who call Torah “the Old Testament” and think that means the Ten Commandments. Millions who think Moses was an orator and Adam a Jew. Rashi an Indian God with a giant shvontz and lots of arms. My father’s own cousin Bernie in Highland Park, Gurion — my family got stuck for the night at his house last January, during that blizzard. In the morning, before davening, I ask Bernie if he has any phylacteries I can use, and after winking slyly, he takes me to the master bathroom and pulls from the cabinet an assortment of condoms. Latex ones, intestines ones, reservoir-tipped, no-tipped, with spermicide or without, anesthetically lubricated purple ones with built-in pleasure-giving rivets. Bernie says I can have as many prophylactics as I want, just as long as I’m safe. Says he won’t tell my parents, I don’t have to worry, it is natural to want to have sex with girls, ‘It is for with girls, right, Emmanuel? Not that if it’s not there’s anything wrong with that,’ he says, chuckling, play-punching my arm, this ability to appreciate a reference to Seinfeld the deepest thing we have in common, two Israelites. So yes. I misspoke. You’re the only one of any relevance —the only scholar with a pennygun — who thinks it matters that you’re ten years old. And before you start talking about your father, or Rabbi Salt, about what they believe, about how that matters, let me do the most obnoxious thing a person can do to his friend. Let me quote you at you. Let me tell you what you told me when I described to you how the implications of Chapter 15 in First Samuel gave me headaches. You said, ‘A prophet is a bright thing, and those who can’t see a bright thing are blind, and those who do see a bright thing can get blind doing so.’ I would suggest to you that your father and Rabbi Salt, wise as they certainly are — they see you and get blind. And let me tell you something else, please, before I lose steam, and this is maybe the most important thing: You’re the only one who thinks you need to be the messiah in order to lead us. It is true that none of us is certain you are the messiah, and it is true that a number of us aren’t even certain you’ll become the messiah — and I have no problem telling you that’s the camp I’m in (though were you to tell me you will become him, I would believe it) — but every single one of us agrees that if you are not already the messiah, you might become him. And not merely because you are a Judite, but because you are Gurion Maccabee. You are the person we want to lead us. We believe you were born to do that. And if following you, as we suspect, turns out to be the environmental condition that makes actual your potential, that would be ideal; but even if following you doesn’t do that, Gurion, we are certain it will still bring about an improvement. We are certain that following you will help bring the messiah, whoever he might be, whether in this generation or the next.”

I really didn’t know what to say. Whenever the subject of my possibly being the messiah got brought up this explicitly at Schechter or Northside, it was always by one of the lesser-abled scholars — most often a first- or second-grader, occasionally a sweet, lower-IQ-type or new kid — and if after I then gave them my thumbnail lecture on potential and actual messiahs, they still failed to take the lesson, I would fix a collar or do some kind of pratfall, and the conversation would end. None of the truly talented scholars had ever brought it up to me directly, let alone Emmanuel, who was the most talented of them all. And after what he’d said, I knew that any of the arguments I came up with would sound like a coy invitation to get annointed. And annointment really wasn’t what I wanted. Like everyone else I knew, I did want to be the messiah, and certainly, at times, I suspected I would be, but at the same time, there was almost nothing I could think of that I wanted less than to be a false messiah. To lose June, to see my parents get hurt — what else besides variations on those two themes? That was it. To be a false messiah would be the third worst thing in the world.

“Rabbi,” said Emmanuel, “You look frustrated. Are you silently pooh-poohing me?”

I said, I just don’t know what to say to you.

“Say that you’ll lead us.”

Lead you how? I said.

“I don’t know,” he said. “ Some how, though. Something needs to be done soon. There is too much strife in the Land of Israel. Everyone agrees.”

I said, There has always been strife in the Land of Israel.

“Exactly,” he said. “And always too much, and everyone has always agreed on that. It’s wisdom as old as history. Something needs to be done already.”

The train slowed and we swayed.

“Aren’t you getting off here?” Emmanuel said.

It was our stop, but Emmanuel could not be seen entering our neighborhood with me, so I told him to go ahead, that I would stay on til Loyola and walk from there.

“It makes me angry, Rabbi — at myself. I’m your student. Why should I have to worry I’ll be seen with you?”

Because you’re a good son, I told him.

“It feels like I’m a coward,” he said. “Either way, I’m the one who should walk the extra blocks — not you. And there’s no time to argue.”

Emmanuel was right.

When the doors slid open, I snatched the yarmulke from his head and flung it onto the platform.

He leapt out to get it, grabbed it and kissed it, and it was only after the train pulled away that I saw we’d created needless drama, that things had actually been simpler than they’d seemed. We could have both disembarked at our stop no problem if one of us had just hung back an extra minute while the other one entered the neighborhood.

I stepped off the train at the next stop, Loyola, and gulped down my last sip of coffee. The nearest garbage barrel was twenty feet away. By the time I got to it, the victory spike felt forced, like a knock on wood, and nothing seemed finished at all.

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

6:30–Bedtime

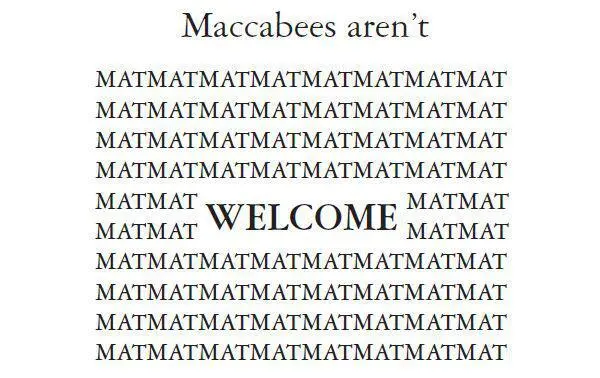

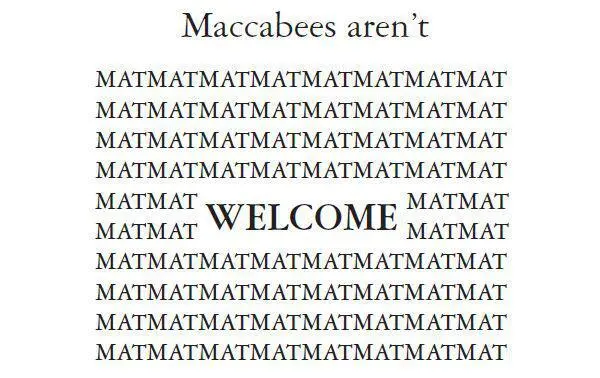

Patrick Drucker wanted to stand on the sidewalk in the Wilmette shopping district and speak through a megaphone while handing out pamphlets about conspiracies. The City of Wilmette didn’t want him to speak or hand out pamphlets, and after he refused a request to desist, the Wilmette police put him under arrest, and Drucker contacted the United Civil Liberties Advocates of America, at which point my father became his lawyer. Patrick Drucker vs the City of Wilmette had been getting publicity for weeks. Closing arguments had begun that morning. My dad was convinced he’d defeat Wilmette, and so was most of the rest of the Chicagoland area — my father always won — but the Israelites of West Rogers Park weren’t happy about that, they never were, and one of them, in protest, had spraypainted “Maccabees aren’t” above the welcome mat on the front stoop of our house. I couldn’t be sure how long the new bomb had been on the stoop — I hadn’t seen the stoop that morning (Tuesday) because I’d left out the back door like my parents, like usual — but I knew it hadn’t been there the afternoon before (Monday), and I had a hard time imagining someone vandalizing a stoop before midnight or after 5 AM, so I figured the vandal had come in the night.

Читать дальше