Shortly after we broke up, I returned from an overnight trip to Poland. I was carrying a heavy bag down a railway platform. I don’t know why I still haven’t bought a wheeled suitcase. And here’s another personal fault of mine, to add to the list: whenever I get upset — or, should I say, agitated — whatever I’m wearing at the time becomes etched permanently into my memory, remaining perfectly clear even after decades. So, I was hauling my bag through the station and suddenly felt it getting lighter behind me, and rising into the air … I turned around, and there, on the platform, sleepy-eyed, was the man for whom the world looked, when he was with me, like bright flashes of countryside seen from a speeding train. “You’re meeting someone here?” I asked him. “I am,” he said, looking into my eyes. And I looked into his, but all I saw were my beige stockings, twisted not once but twice; my face bedraggled from two border crossings; the beret covering my greasy hair; and the bandage on the heel of my right foot. And if my bag were to continue the story, the events on the platform might play out like so: “The man carried me to a car and threw me into its empty trunk. But my owner lifted me out again. ‘Don’t be silly,’ the man said. ‘It’s Christmas, look at how many people are waiting at the trolleybus stop, let me take you to Panev  žys.’ The man got into the driver’s seat, flicking the toy spider dangling from his rearview mirror, while the woman walked off, heading for the bus station. Waiting in line for a ticket, she put me down on the muddy floor and then fell right on top of me; I expected my ribs — made up of books, boxes, cans, and shoes — to tear through the skin at my sides. I remembered then that fifteen hours before, at the departures tracks, a different man had seen my owner off. They kissed on the platform. I suppose she must have thought that a different man unexpectedly meeting her on her return was some sort of sin?” I thought about how I would behave now. I would probably have gone to hell with him, that man for whom the naked body, unrelated to the soul, was just another material, like so many others — clay, asbestos, silk. But, then, who really knows where we board the train to hell. Where its tracks begin, where they end, or what’s waiting there?

žys.’ The man got into the driver’s seat, flicking the toy spider dangling from his rearview mirror, while the woman walked off, heading for the bus station. Waiting in line for a ticket, she put me down on the muddy floor and then fell right on top of me; I expected my ribs — made up of books, boxes, cans, and shoes — to tear through the skin at my sides. I remembered then that fifteen hours before, at the departures tracks, a different man had seen my owner off. They kissed on the platform. I suppose she must have thought that a different man unexpectedly meeting her on her return was some sort of sin?” I thought about how I would behave now. I would probably have gone to hell with him, that man for whom the naked body, unrelated to the soul, was just another material, like so many others — clay, asbestos, silk. But, then, who really knows where we board the train to hell. Where its tracks begin, where they end, or what’s waiting there?

There are people with whom it wouldn’t be frightening to travel to hell. One of them is my cousin; for all I know, he’s already been there. The conductor of the universe. He doesn’t have the time for such long trips anymore. He’s working off his debts. He despises wealth, but he can’t stand to live anywhere “cramped.” When he bought his apartment, he borrowed a portion of the money in cash from an American Lithuanian, an old lady who’d been using him as a free computer repair service for years. He’d swear a blue streak about what he went through in her place; sweeping aside all the velvet-framed pictures in of her grandchildren and great-grandchildren in order to reach the keyboard, and then being forced to listen to her endless stories of their victorious college baseball teams … “How are you planning to pay her back all that money?” I asked. “Oh, you’re such a worrier … How, how? I’ll tell you how: the way large sums of money are exchanged in the movies … In a suitcase, in rows, wrapped in little packs.” Back when he had a jeep, we used to drive out to the swamps. My cousin would drag along a suitcase full of unwanted possessions or other leftovers from remodeling his new apartment — broken skis, unused bits of floorboard, computer monitor boxes, other pieces of cardboard, and stacks of paper — dropping them at the nearby dump. But the swamps next to Trakai have been fixed up nicely now. Without even stepping off the boardwalk you can reach a thin, nearly-transparent birch, bend its trunk down all the way to the ground, let it go, and watch it spring back into its original position, since its roots have fixed themselves into the greenery at the bottom of the reservoir. There’s a floating observation post built out on the lake. We’d spread cheese, bread, and tea on the bench and watch, as people say, “junipers growing gin.” There’s never many people there, even in July. Toward evening we met two men from Sweden with a movie camera; they hoped to find some rare birds, perhaps a curlew, in that landscape already browned like a poor-quality photograph. On the narrow path, we passed a silent family whose members seemed as though they’d already been bored with each other centuries ago: a mother, two teenaged boys behind her, and father leading a Great Dane. The dog’s muzzle looked like the bars of a jail; I pictured them all trapped inside. By the time we’d gotten back to dry land, by now the only visitors in sight, my cousin was only carrying his knapsack. “You left your suitcase back there,” I said. “What will you use to carry your next load of garbage to the dump?” “What, what. Oh, you’re such a worrier. I don’t need it anymore. I’ve finally dug my way out. There’s nothing left to throw away.” Whenever I remember returning from somewhere, I take leave of it all over again. I imagine how the place went on, after me, objectively. “The southern part of the reserve extends over 207 hectares, in which there are four small lakes: Baluošas, Piliški  , Bevardis, and Ilgelis. These little lakes are in fact the remnants of what was once a single, larger lake. The Dumbl

, Bevardis, and Ilgelis. These little lakes are in fact the remnants of what was once a single, larger lake. The Dumbl  , which has turned into a bog, lies to the north of Ilgelis. All the lakes of the Varnikai reserve are fed by the swamps surrounding them. The swamp water rises nearly a meter higher than the level of Bernardin

, which has turned into a bog, lies to the north of Ilgelis. All the lakes of the Varnikai reserve are fed by the swamps surrounding them. The swamp water rises nearly a meter higher than the level of Bernardin  (Luka) Lake. The excess water flows through irrigation canals to Bernardin

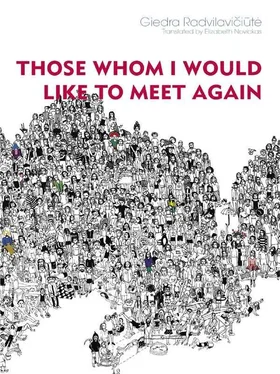

(Luka) Lake. The excess water flows through irrigation canals to Bernardin  Lake, so the lower edges of the marsh have been reclaimed and are now grown over with bushes, while the highland is covered in pine and birch. Indigenous fauna has not been extensively researched, but local lore suggests that many rare species of bird breed in this area.” And, as far as flora, if you were to dive beneath the chill waters of the lake with a movie camera, you’d find everything there: canes, rushes, cattails … While in the formless, saprophytic mass of decomposing plants and animals, you’d also find an abundance of embedded trash, the largest of which is an old suitcase. Inside it — an old lady, sliced up into pieces. Judging from the two gold rings on the nameless lady’s finger, she was an American Lithuanian. Inscriptions: “To Peter, With Love. To Birute, With Love. Detroit, 1950.” I’d like to meet my cousin again, too. But how? “How, how! Don’t be such a worrier. I live, after all, in every one of your stories.”

Lake, so the lower edges of the marsh have been reclaimed and are now grown over with bushes, while the highland is covered in pine and birch. Indigenous fauna has not been extensively researched, but local lore suggests that many rare species of bird breed in this area.” And, as far as flora, if you were to dive beneath the chill waters of the lake with a movie camera, you’d find everything there: canes, rushes, cattails … While in the formless, saprophytic mass of decomposing plants and animals, you’d also find an abundance of embedded trash, the largest of which is an old suitcase. Inside it — an old lady, sliced up into pieces. Judging from the two gold rings on the nameless lady’s finger, she was an American Lithuanian. Inscriptions: “To Peter, With Love. To Birute, With Love. Detroit, 1950.” I’d like to meet my cousin again, too. But how? “How, how! Don’t be such a worrier. I live, after all, in every one of your stories.”

As for the old ladies I’ve met, I’d like to meet almost all of them again. Particularly the ones in Kie  lowski’s movies. With purses of cracked oilskin hanging on their arms, they go up to dumpsters, stand on their tiptoes, and — reaching over the lip with great difficulty — try to get their empty bottles down into the hole, holding these by their tips; they push and shove the way men would shove a heavy rowboat into the water. (This year, by reducing pensions and other such expenses by ten percent, it will be possible for the government to save 510 million. “People don’t earn pensions; they earn the possibility of getting one.”) Come to think of it, I’d like very much to meet one particular old lady who got written up in the newspapers — but they say she doesn’t let anyone near. She’s been afraid of people for sixty years now, since the day she was raped by soldiers. Although she was very pretty, she stayed in a remote village to live in poverty with her half-witted brother, who liked to play the accordion on Sundays. And we know all about those village Sundays, don’t we — a hard-boiled egg steaming; a fly banging into the window; a ray of sunshine, as if it were alive, crawling out from behind the clouds and cleaving the room in two. Tarkovsky could have had his soundman record a tearing cobweb in a remote village, just to check his equipment. Last summer I checked for myself whether this business of hearing a cobweb tear was even possible, given the exploitation of this conceit by writers … not least this one. (A cobweb tears like wet gauze, and the sound can indeed be heard, by ordinary ears, in complete silence … if you aren’t thinking about anything else at that moment.) That old lady never went anywhere, except the cemetery, to visit her father and mother’s graves. When she had tidied the perennials, she would leave her little rake behind a fence and, before heading for home, she would lay down on the loosened soil, the way others would lay on a memory-foam mattress. When some drunken thieves broke down her cottage door, looking for hidden pension money, and beat her brother savagely, she tried to bandage his head with rags, but by the next day he had gone cold. The old lady never even reported the misfortune to the village officials. She was afraid. She wrote a note, put it into the open case of the accordion, and left it on the road. I’d write about this old lady in more detail if someone asked me to compose a text for the national dictation contest. I know what a text like that needs: love for the homeland, a bit of history and hope. Well, and some special grammatical forms, so that people don’t forget that the accusative inflection for nouns gets an ogonek (little tail), and pronominal numerals and adjectives even get two (for example, per Antr

lowski’s movies. With purses of cracked oilskin hanging on their arms, they go up to dumpsters, stand on their tiptoes, and — reaching over the lip with great difficulty — try to get their empty bottles down into the hole, holding these by their tips; they push and shove the way men would shove a heavy rowboat into the water. (This year, by reducing pensions and other such expenses by ten percent, it will be possible for the government to save 510 million. “People don’t earn pensions; they earn the possibility of getting one.”) Come to think of it, I’d like very much to meet one particular old lady who got written up in the newspapers — but they say she doesn’t let anyone near. She’s been afraid of people for sixty years now, since the day she was raped by soldiers. Although she was very pretty, she stayed in a remote village to live in poverty with her half-witted brother, who liked to play the accordion on Sundays. And we know all about those village Sundays, don’t we — a hard-boiled egg steaming; a fly banging into the window; a ray of sunshine, as if it were alive, crawling out from behind the clouds and cleaving the room in two. Tarkovsky could have had his soundman record a tearing cobweb in a remote village, just to check his equipment. Last summer I checked for myself whether this business of hearing a cobweb tear was even possible, given the exploitation of this conceit by writers … not least this one. (A cobweb tears like wet gauze, and the sound can indeed be heard, by ordinary ears, in complete silence … if you aren’t thinking about anything else at that moment.) That old lady never went anywhere, except the cemetery, to visit her father and mother’s graves. When she had tidied the perennials, she would leave her little rake behind a fence and, before heading for home, she would lay down on the loosened soil, the way others would lay on a memory-foam mattress. When some drunken thieves broke down her cottage door, looking for hidden pension money, and beat her brother savagely, she tried to bandage his head with rags, but by the next day he had gone cold. The old lady never even reported the misfortune to the village officials. She was afraid. She wrote a note, put it into the open case of the accordion, and left it on the road. I’d write about this old lady in more detail if someone asked me to compose a text for the national dictation contest. I know what a text like that needs: love for the homeland, a bit of history and hope. Well, and some special grammatical forms, so that people don’t forget that the accusative inflection for nouns gets an ogonek (little tail), and pronominal numerals and adjectives even get two (for example, per Antr  j

j  pasaulin

pasaulin  ; kar

; kar  [“during the Second World War”]). As far as consonant assimilation, a voiced consonant next to an unvoiced one gets muffled (she stayed to live in poverty with a halfwit).

[“during the Second World War”]). As far as consonant assimilation, a voiced consonant next to an unvoiced one gets muffled (she stayed to live in poverty with a halfwit).

Читать дальше

žys.’ The man got into the driver’s seat, flicking the toy spider dangling from his rearview mirror, while the woman walked off, heading for the bus station. Waiting in line for a ticket, she put me down on the muddy floor and then fell right on top of me; I expected my ribs — made up of books, boxes, cans, and shoes — to tear through the skin at my sides. I remembered then that fifteen hours before, at the departures tracks, a different man had seen my owner off. They kissed on the platform. I suppose she must have thought that a different man unexpectedly meeting her on her return was some sort of sin?” I thought about how I would behave now. I would probably have gone to hell with him, that man for whom the naked body, unrelated to the soul, was just another material, like so many others — clay, asbestos, silk. But, then, who really knows where we board the train to hell. Where its tracks begin, where they end, or what’s waiting there?

žys.’ The man got into the driver’s seat, flicking the toy spider dangling from his rearview mirror, while the woman walked off, heading for the bus station. Waiting in line for a ticket, she put me down on the muddy floor and then fell right on top of me; I expected my ribs — made up of books, boxes, cans, and shoes — to tear through the skin at my sides. I remembered then that fifteen hours before, at the departures tracks, a different man had seen my owner off. They kissed on the platform. I suppose she must have thought that a different man unexpectedly meeting her on her return was some sort of sin?” I thought about how I would behave now. I would probably have gone to hell with him, that man for whom the naked body, unrelated to the soul, was just another material, like so many others — clay, asbestos, silk. But, then, who really knows where we board the train to hell. Where its tracks begin, where they end, or what’s waiting there? , Bevardis, and Ilgelis. These little lakes are in fact the remnants of what was once a single, larger lake. The Dumbl

, Bevardis, and Ilgelis. These little lakes are in fact the remnants of what was once a single, larger lake. The Dumbl  lowski’s movies. With purses of cracked oilskin hanging on their arms, they go up to dumpsters, stand on their tiptoes, and — reaching over the lip with great difficulty — try to get their empty bottles down into the hole, holding these by their tips; they push and shove the way men would shove a heavy rowboat into the water. (This year, by reducing pensions and other such expenses by ten percent, it will be possible for the government to save 510 million. “People don’t earn pensions; they earn the possibility of getting one.”) Come to think of it, I’d like very much to meet one particular old lady who got written up in the newspapers — but they say she doesn’t let anyone near. She’s been afraid of people for sixty years now, since the day she was raped by soldiers. Although she was very pretty, she stayed in a remote village to live in poverty with her half-witted brother, who liked to play the accordion on Sundays. And we know all about those village Sundays, don’t we — a hard-boiled egg steaming; a fly banging into the window; a ray of sunshine, as if it were alive, crawling out from behind the clouds and cleaving the room in two. Tarkovsky could have had his soundman record a tearing cobweb in a remote village, just to check his equipment. Last summer I checked for myself whether this business of hearing a cobweb tear was even possible, given the exploitation of this conceit by writers … not least this one. (A cobweb tears like wet gauze, and the sound can indeed be heard, by ordinary ears, in complete silence … if you aren’t thinking about anything else at that moment.) That old lady never went anywhere, except the cemetery, to visit her father and mother’s graves. When she had tidied the perennials, she would leave her little rake behind a fence and, before heading for home, she would lay down on the loosened soil, the way others would lay on a memory-foam mattress. When some drunken thieves broke down her cottage door, looking for hidden pension money, and beat her brother savagely, she tried to bandage his head with rags, but by the next day he had gone cold. The old lady never even reported the misfortune to the village officials. She was afraid. She wrote a note, put it into the open case of the accordion, and left it on the road. I’d write about this old lady in more detail if someone asked me to compose a text for the national dictation contest. I know what a text like that needs: love for the homeland, a bit of history and hope. Well, and some special grammatical forms, so that people don’t forget that the accusative inflection for nouns gets an ogonek (little tail), and pronominal numerals and adjectives even get two (for example, per Antr

lowski’s movies. With purses of cracked oilskin hanging on their arms, they go up to dumpsters, stand on their tiptoes, and — reaching over the lip with great difficulty — try to get their empty bottles down into the hole, holding these by their tips; they push and shove the way men would shove a heavy rowboat into the water. (This year, by reducing pensions and other such expenses by ten percent, it will be possible for the government to save 510 million. “People don’t earn pensions; they earn the possibility of getting one.”) Come to think of it, I’d like very much to meet one particular old lady who got written up in the newspapers — but they say she doesn’t let anyone near. She’s been afraid of people for sixty years now, since the day she was raped by soldiers. Although she was very pretty, she stayed in a remote village to live in poverty with her half-witted brother, who liked to play the accordion on Sundays. And we know all about those village Sundays, don’t we — a hard-boiled egg steaming; a fly banging into the window; a ray of sunshine, as if it were alive, crawling out from behind the clouds and cleaving the room in two. Tarkovsky could have had his soundman record a tearing cobweb in a remote village, just to check his equipment. Last summer I checked for myself whether this business of hearing a cobweb tear was even possible, given the exploitation of this conceit by writers … not least this one. (A cobweb tears like wet gauze, and the sound can indeed be heard, by ordinary ears, in complete silence … if you aren’t thinking about anything else at that moment.) That old lady never went anywhere, except the cemetery, to visit her father and mother’s graves. When she had tidied the perennials, she would leave her little rake behind a fence and, before heading for home, she would lay down on the loosened soil, the way others would lay on a memory-foam mattress. When some drunken thieves broke down her cottage door, looking for hidden pension money, and beat her brother savagely, she tried to bandage his head with rags, but by the next day he had gone cold. The old lady never even reported the misfortune to the village officials. She was afraid. She wrote a note, put it into the open case of the accordion, and left it on the road. I’d write about this old lady in more detail if someone asked me to compose a text for the national dictation contest. I know what a text like that needs: love for the homeland, a bit of history and hope. Well, and some special grammatical forms, so that people don’t forget that the accusative inflection for nouns gets an ogonek (little tail), and pronominal numerals and adjectives even get two (for example, per Antr  j

j  pasaulin

pasaulin