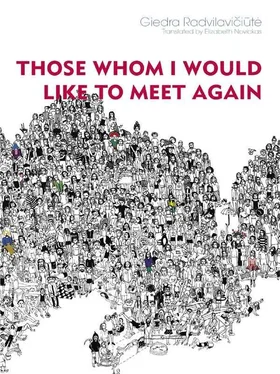

Those Whom I Would Like to Meet Again: An Introduction

Salinger wrote a story called “Seymour: An Introduction.” Seymour Glass, the narrator’s brother — who didn’t actually exist, but then existence isn’t always a requirement for brothers — committed suicide in another story while vacationing with his wife in an ocean-side hotel room smelling of veal and nail polish. When Seymour prepares to go swimming with a small girl staying in the same hotel, no one — neither the other beachgoers, nor anyone reading the story for the first time — suspect that he will shoot himself at the end of the story. That’s the way a story’s ending should be — unpredictable. Perhaps it seems to the reader that she will indeed read a story about a perfect day for catching bananafish: “He unrolled the towel he had used over his eyes, spread it out on the sand, and then laid the folded robe on top of it. He bent over, picked up the float, and secured it under his right arm. Then, with his left hand, he took Sybil’s hand. The two started to walk down to the ocean.” I really do think that great literature has died. Which is why ending a story with death has fallen out of fashion. Almost all contemporary art is intended to help us forget death, after all.

All of those whom I would like to meet again (excepting Seymour) really do exist. I like to remember them when I have a moment to myself — now, for example. I bought food for supper, because here, in the summerhouse, there’s a kitchen. I went swimming twice — strange, it’s the beginning of August, and the water in the sea is sixty-four degrees. Tomorrow it’s supposed to be horribly windy. The smell of seaweed will penetrate the pinewoods. The waves will break in crests, and like in the famous Lithuanian artist’s painting, splash the initials MK  (Mikalojus Konstantinas

(Mikalojus Konstantinas  iurlionis) on the water. I’ll walk barefoot on damp sand that’s like minnow spawn thrown out on the beach. And now I’m waiting for a friend to arrive. In the evening we’ll watch a bad movie starring a good actor — Mickey Rourke, having emerged from the quagmire of alcohol and drugs, plays a wrestler. In his youth, he worked out his anger boxing, incidentally, in the same state where Seymour killed himself. Everything in the world, or almost everything, is connected.

iurlionis) on the water. I’ll walk barefoot on damp sand that’s like minnow spawn thrown out on the beach. And now I’m waiting for a friend to arrive. In the evening we’ll watch a bad movie starring a good actor — Mickey Rourke, having emerged from the quagmire of alcohol and drugs, plays a wrestler. In his youth, he worked out his anger boxing, incidentally, in the same state where Seymour killed himself. Everything in the world, or almost everything, is connected.

When you’re waiting for the arrival of a very close friend or loved one, you usually do have some idea where she is and what she’s doing. I could call her, of course, but why bother, when I can see her so clearly? At a log-built donut shop and convenience store, next to the freeway, not even having reached Kryžkalnis yet. The grass at the side of the road is beginning to brown. There are colored inserts from the Sunday paper and plastic bottles scattered around. Ideally, the car radio isn’t turned on; worst-case scenario, it’s “Pretty woman, walking down the street,” or “I can’t get no satisfaction, I can’t get no …” My friend looks at a bottle of brandy for a long time, but she resists and buys kvass, a donut, and some real wax candles poured by local craftspeople — one in the shape of an angel, the other of a phallus. She’ll be here in approximately an hour and a half. After parking her car in the lot, across the little lawn, directly across from the window at which I’m sitting, she’ll walk straight through the grass rather than up the sidewalk and around, saving herself approximately two meters, a Parliament cigarette clenched in her teeth all the while: “You couldn’t come out and help?” she’ll say. “Didn’t you see my hands were full? Oh, Tadas called from his ‘sports camp.’ The toilet’s in another building, so he and his roommate pee into a mineral water bottle. I brought him the icing from a donut, towels, gym shoes, and clean bedding, because nothing dries there. You won’t mind if he spends the night here? With his friend? Yesterday someone stole a hundred litai from them, and their gym shoes too.” And she’ll kick the pink crocuses by the door, but by the time she’s finished scattering around the clothes, towels, and mattresses she brought along for the weekend, by the time she’s adorned the dresser with that framed black-and-white photo of a soldier she takes everywhere (I think of it as a portable Tomb of the Unknown Soldier), as well as her prescription glasses (-10.00 / -6.00), by the time she’s poured herself some brandy from the bottle I’ve left on the table, by the time she’s announced that people her age just aren’t cut out for driving three hundred kilometers a day (yesterday she was all the way at the other end of Lithuania, at a funeral), by the time she thinks to have another smoke, her story about the funeral she just attended will have begun to break apart and die away, until it finally sputters out. In the dusk of the room I’ll soon see only my friend’s bare knees, the red point of her cigarette, and her six gesticulating arms. Dusk is my favorite time of day: sounds become muffled, less shrill; the cellophane of the air turns to flannel; ponds begin to reflect the netherworld; things turn into other versions of themselves; and characters from novels pour into the streets … I don’t know where they come from, but they float about as quietly as sentences. “Now, that’s how he’ll take two hectares of land away from me,” my friend will say, pointing at the refrigerator with her middle finger. “As far as I’m concerned, if he couldn’t help carry the coffin yesterday, he shouldn’t get the land — for that reason alone! The coffin was hardly heavy. When he got sick, my uncle turned from an oak to stewed rhubarb.”

Whoever will or won’t get those two hectares will have to remain anonymous to me for now. I’ll have missed a good portion of the story by getting distracted by thoughts of how it happened that this woman became my best friend. A friend who, like the others I would like to meet again, is impossible to write about objectively, because love gets in the way. Salinger isn’t the only one who noticed this contradiction; Seymour: An Introduction has an epigraph from Kafka: “ … I write about them with steadfast love (even now, while I write it down, this, too, becomes false) but varying ability, and this varying ability does not hit off the real actors loudly and correctly but loses itself dully in this love that will never be satisfied with the ability and therefore thinks it is protecting the actors by preventing this ability from exercising itself.”

I could have spent my weekend alone in the quiet, but I invited her here, and I suspect I’ll have to put Salinger aside on the windowsill for the duration. The only things my friend has ever read are Zoshchenko’s stories, and those not very carefully. When she needs to express herself, she resorts to Russian; she came late to Lithuanian. She’s the sort of person who constantly changes channels while watching television, clicking away at the remote control; I can’t stand that. (We’ll go to bed without watching The Wrestler ; it’s obvious what a sbornik , a scumbag, Rourke is, she’ll say.) Her expenses never correspond to her income: she used to say that God had created too little money for the world, so she was borrowing it from the devil. She has no concept of the boundaries of “decent” conversation, crossing them at will. (“If I had to choose between oral sex or jellied carp, I’d go with the fish.”) She’s always playing with words, switching them around, wrong-footing you at just the right moment. (“The exception disproves the rule!”) She likes to steal amusing signs from public places. The most valuable item in her collection is a sign she took from a changing room at a swimming pool: “Please refrain from using the hairdryers for hair anywhere but on your head.” She’s scheduled to have a valve replaced in her heart this year. She’s still waiting, though; the same way I’d wait in a store for them to exchange a pair of shoes for one that’s my size. She’s always imagined she’d die the way her grandfather did. From a heart attack. Playing solitaire on a glassed-in veranda in the evening light. And, in the garden beyond the glass, as on a computer screen, the neighbor’s grandchildren running about. Rain water in a bucket stirred by a fleck of dust. Winter apples strewn here and there by the windowsill. Three zucchini crocodiles and a fattened pumpkin lying on the nearby couch. Her knees bending slowly, she starts sliding sideways from her wicker chair. Her startled cat leaps from her lap into eternity, while a card falls out of her relaxing fingers.

Читать дальше

(Mikalojus Konstantinas

(Mikalojus Konstantinas