‘That’s total shit,’ Shani said. ‘Are you telling me that every time a Jewish parent objects to his child marrying out, what he actually wants is someone to kick him?’

‘In the toches,’ Mick added.

‘No. What he actually wants is his child not to marry out. But what he wants and what he is seeking might not be the same thing. Though it might also be the case that the kicking, if and when it comes, will ultimately harden his conviction that he is a thing apart, a victim of a brutal Jew-hating world, which he is therefore right to save his child from if he can.’

‘Total shit,’ Shani repeated.

Throughout all this my mother regarded me with a prunelike expression. She didn’t like fancy explanations. You won at kalooki if you had a good knowledge of the deck and could anticipate what the other players were thinking. You worked on the straightforward assumption that they wanted to win. If you had to take on board the possibility that what they really wanted was to lose — well, frankly you wouldn’t know where you were.

But she wasn’t going to say anything that might add fuel to the fire. She had grown to love Mick Kalooki. And her brother was her brother. She got up from the table, loped her long Ethiopian stride across the room, sat in an armchair and crossed her legs. When you saw my mother’s ankles you wanted to cry. They were the best argument for Judaism — its golden allure, its sensuality and its fragility — I had ever encountered. Why, then, I was otherwise attracted; why, when I had grown up with this rich aroma of spiced indolence around me I let my nose lead me in the direction of flesh that was by comparison odourless and colourless, I was not at that time — not having yet done ‘Introduction to Psychology II’ — in a position to understand.

As for Tsedraiter Ike, he came out of his room at last and resumed his visits to the houses of the Jewish dead. He never addressed a word to Mick Kalooki again. Nor did Shani — against all Mick Kalooki’s attempts at conciliation — address another word to him. When Ike died, Mick attended his funeral, hung his head and even shed a tear. Shani stayed at home.

5

I never liked the expression ‘stiff-necked’, but yes, as I conceded to Chloë’s mother in the course of what I now realise had been planned as a goodbye and good-riddance tea, we were an implacable people. ‘I doubt we are that by nature,’ I told her. ‘Nobody is anything by nature, Helène, unless we make an exception of your Judaeophobia. But by bitter experience. Kill or be killed.’

‘Bit OTT, your soon to be ex-hubby, Chlo,’ she’d said, taking a scone from my plate and wiping it on the sleeve of her blouse, while I sweated to think of a county that had ‘fuck you’ in it.

But yes. We were, by bitter experience, an implacable people. And we had with reason come to believe that it was only by being implacable that we had survived. True, some of us had had a go at being lenitive. Behold, we are an accommodating bunch. But the last time we had a serious go at that was in Germany. The Haskalah, as we called it. The Enlightenment. Our love affair with the Kraut. And you don’t go making that kind of mistake twice.

I wanted to do my best imaginatively by Channa and Selick Washinsky, anyway. As I wanted to do my best by Manny. A moral balancing act of some complication, I accept. Of course you want to have your son sectioned when he falls in love for the second time with the same shikseh. And of course you, Manny, know that for wanting him sectioned they no longer deserve to be among the living.

It was partly to simplify my own feelings that I said to him later that same afternoon, after we too had broken off for tea, ‘Christ, Manny, did it never occur to them just to go out and buy a gun and have done with it?’

He had been pulling at his fingers throughout our conversation, cracking them one by one, pulling at them as though he meant systematically to take his hands apart. ‘No,’ he said, after taking his time to think about it, not looking in my direction, not looking anywhere, ‘I don’t think so. But it occurred to me .’

I laughed. ‘I don’t see you with a gun, Manny.’

‘Why not?’

‘I just don’t see it. You don’t go together. You and guns? Forgive me — it’s too incongruous.’

‘You think I wouldn’t know how to use one?’

‘I can’t see it in your hand. I can’t picture it. If I imagine a gun in your hand it falls out. I mean that as a compliment.’

‘So why are you laughing?’

‘To express solidarity with your humanity. I can’t picture a gun in my hand either. We were brought up to carry books, not guns,’

‘That’s not what they say in Israel.’

‘Israel’s different. You don’t laugh in Israel.’

‘You wouldn’t laugh here if I was pointing a gun at you.’

‘I don’t know about that, Manny. Maybe I would.’

‘I bet you wouldn’t.’

‘I couldn’t take your money.’

‘Do you want to try?’

I laughed again, though not as easily as I had the first time. ‘No,’ I said, ‘I very much don’t want to try.’

The problem with Bernie Krigstein was that he didn’t have much of a sense of fun. In the end there are only two sorts of Jews, and I don’t mean those who went through the Holocaust and those who only thought they did. I mean Jews who see the funny side of things and those who don’t. The mistake is to suppose that those who see the funny side of things become cartoonists, and those who don’t go into law. It’s often the other way round. Krigstein made history with his comic-book story ‘Master Race’ because it wasn’t comic. Not a line of it that wasn’t sombre. ‘Krigstein didn’t understand the humor,’ said Harvey Kurtzman, who employed him for a while on Mad . By ‘the humor’, he meant pretty well the humour of anything he was given to illustrate. ‘He did funny grimnness,’ Kurtzman went on. ‘Grimness in slapstick.’ Not that there’s anything you can call slapstick in ‘Master Race’. But then you could argue that commandants of death camps don’t as a rule give rise to slapstick much.

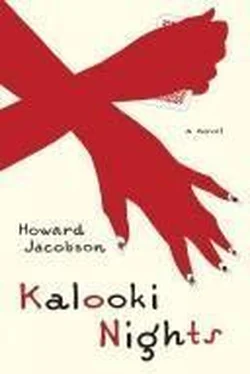

I don’t know. I never knew. It could have been the house I grew up in — my father’s punchy scepticism, my mother’s deathdefying kalooki nights, or just the physical and psychological ludicrousness of Tsedraiter Ike — but for me nothing was so dreadful that I couldn’t see its essential drollery. This could explain why drawing Superman was ultimately beyond me. In my hands Superman’s X-ray vision would only have revealed the absurdity at the heart of things. And that included Manny. Here he was, implying he had it in him to be a hit man, and I was supposed to take him seriously. It was so preposterous that I momentarily forgot he was a hit man, a man accused and convicted of the murder of his mother and father.

Guns were the problem. For me guns belonged to an inconceivable universe. Not only could I never have pulled a gun myself, I couldn’t draw one. I could no more credit a gun with presence than I could the bulge in Tom of Finland’s pants. As for whether Manny had ever owned, or, as he seemed to want to menace me into believing, still owned a gun, I didn’t know what I thought. But the idea was gathering that I ought to be thinking something.

It’s a form of disrespect, of course, I acknowledge that, not being able to grant a person the dignity of taking him entirely seriously. But that comes with the territory. Don’t expect respect from a cartoonist.

Historically, the laugh was on the sort of man I was. Without any doubt I would have been among those who pooh-poohed the idea that Nazism in 1930s Germany posed any personal danger to me. Housed snugly in the Berlin suburbs, penning Grosz-like satires on pig-faced bürgerlich nationalism in the daytime, and slipping out at night to perform cunnilingus on Zoë under a table at Der Blau Angel, I would have hung on until the final hour and beyond, convinced that violence was a joke at heart, that no one beyond the occasional ruffian felt any differently about guns than I did. Even on the Jew Jew train I cannot imagine myself ever really believing that the guns were made of anything but cardboard or that they were taking us anywhere but to the seaside.

Читать дальше