Iva, svid , two expressions that could even be left untranslated (as often happens), indicate that we are crossing the threshold of hidden thoughts. According to Renou and Silburn, “the word iva accentuates indetermination, evokes latent values.” In the same way that svid above all accompanies questions in which enigmas are voiced. There were two ways of introducing into discussion that aspect of the anirukta , of the “unexplicit” that is destined to remain so, ever shifting but always encircling the spoken word like a halo. Since thought proceeded by way of identifications, comparisons, equivalences, iva was a reminder that everything said was to be understood “in a certain way,” without becoming fixed in its identity. Which of itself does not exist — or at least only “so to speak,” iva.

* * *

In the troubled history of the Brāhmaṇas, after much insult and abuse, the day of reckoning at last came. It happened in July 1959, at the Indological conference held at Essen-Bredeney. An eminent Indologist, Karl Hoffmann, stood up to deliver a few words that sounded like a long-awaited Supreme Court ruling: “The monuments of Vedic prose (the saṃhitās of the Black Yajur Veda and the Brāhmaṇas) are, as the immensity of the twelve principal works that they contain is already proof by itself, the literary precipitate of a significant period in the history of the spirit and religion, stretching from the Ṛgveda , India’s most ancient literary monument, to the Upaniṣads. The contents of these monuments in prose are made up of theological discussions on the rituals of Vedic sacrifice. The arguments they present often seem devoid of meaning, which is why Max Müller could describe them as ‘the twaddle of idiots and the raving of madmen.’ This may be explained, however, through the magical vision of the world that dominates here (Stanisław Schayer). And they constitute furthermore, as a sort of ‘prescientific science’ (Hermann Oldenberg), the germ cell of the speculative thought of the Indians.”

Unwieldy, solemn, perfectly right. The French school, in truth, from Sylvain Lévi to Mauss, Renou, Lilian Silburn, Mus, Minard, and Malamoud, hadn’t felt the need to issue such a declaration of principle. They all knew that the Brāhmaṇas were an immense and largely unexplored mine of thoughts — and they were not concerned about declaring it. They concentrated instead on the task of bringing the texts to light and connecting them to one another. But we know that German science always needs legitimation. And so, on that July day, Karl Hoffmann assumed the responsibility of formally accepting, after almost three thousand years, the formless and semiclandestine corpus of the Brāhmaṇas among those works of thought that can be classed as indispensable to humanity. It was as if a group of patients had suddenly been moved from a mental hospital to an academy.

* * *

During the early years of the twentieth century, anthropologists were divided in two rival camps: one declared that ritual preceded myth, the other that myth preceded ritual. Childish squabbles — as became apparent a few years later. Mauss saw it as such from the very beginning. For him it was clear that “myth and ritual cannot be dissociated except in the abstract”—and he wrote this in 1903. The important thing was not to set illusory, unfounded precedents — on one side or the other — but to show “the interpenetration of ritual and myth, to reveal the living organism which they form through their union.” And thirty years later he would devote an entire course, using Strehlow’s evidence from Australia, to illustrate cases of perfect interdependence between ritual and myth, that showed “their solidarity, their intimacy.” On the one hand, ritual appeared each time as a “dramatic representation (verbal and physical) of myth,” whereas myth, if construed as a simple story and “detached from its cult necessities,” ended up revealing itself to be “without real foundation, without practical essence and without symbolic flavor.”

But it was exactly this that required an explanation. Why do particular gestures have meaning only if they are based on a story? Why do particular stories need to be told through particular gestures? Here we approach a riddle that lies hidden in the depths of the mind. It is the riddle of the simulacrum , of the eídōlon , of the image that must become visible in order to be effective. This is a characteristic not just of certain cultures, but of whatever culture, in the same way that Pythagoras’s theorem, though formulated in Greece at a particular time, and in Mesopotamia even earlier, did not belong only to the Greek or Mesopotamian cultures, since it is universally applicable. Yet a certain degree of lucidity has to be achieved in a particular place and at a particular time over certain relationships. What Mauss described as the necessary “intimacy” between myth and ritual, the interaction between liturgy and story, had perhaps never been so clear and so effectively put into action as in the time and in the doctrine of the Brāhmaṇas. It should not, therefore, be a case of anthropology bending benevolently over the Brāhmaṇas to extract some still useful relic from the jumble. But the Brāhmaṇas themselves might help anthropology to recognize something on which its whole practice is based.

Man’s initial state is formless, opaque, composite, and also “impure.” Man is a being who “speaks untruth.” He could carry on living like this, though leaving no significant trace. Otherwise he must compose a series of connected gestures that make an “action,” karman. The quintessential action, the one that presupposes and assures that gestures have a meaning, is the sacrificial work.

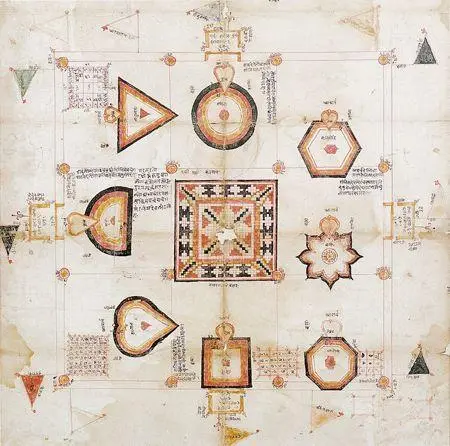

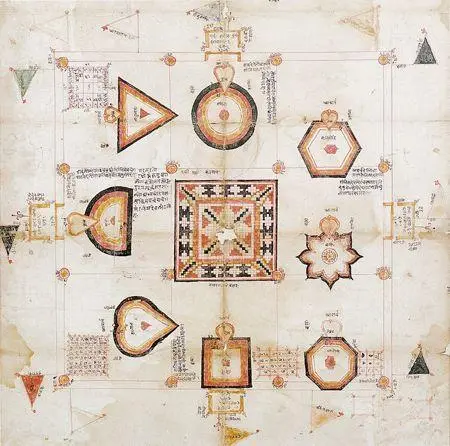

But what is the origin of this work whose first peculiarity is that of being the model for all other work? Desire. Not a general, roving, multifarious, shifting desire — for “mortal man has many desires” and this plurality of desires dwells unremittingly within him from the first to the last moment of his life — but a single desire that seeks to detach itself from every other, to break its ties with the mesh of other desires and find the path to fulfillment. How? By becoming a “vow,” vrata. Entering a vow is like entering another space, that of detached desire, which binds itself, barricades itself from the outside world, and builds a sequence of gestures within the new space that reaffirm it each time. What then is the first of these gestures? To touch water. But not anywhere. To touch it on a point of the invisible line that joins the āhavanīya fire and the gārhapatya fire. This is the line of the fires. The gārhapatya , “domestic,” hearth is circular, sited to the west. There the fire is lit. There burn the embers with which the other fires will be lit. Not far away, to the east, on any type of ground, freshly swept with palāśa branches ( Butea frondosa , Flame of the Forest, but it should also be thought of as brahman ), a square hearth is built, called āhavanīya. On this fire the oblations will be offered — and it can be lit only with an ember taken from the gārhapatya fire. The āhavanīya fire is the sky, the gārhapatya fire is the earth (and it is circular since the earth is a circle at the center of other circles.) Between the two fires is the atmosphere, where we breathe, where we act. In the middle there is also “the trunk of the body,” where the heart, life, beats. There are other fires, but these two must be set up first: āhavanīya and gārhapatya. They provide the tension on which everything rests. Everything is supposed to happen on the invisible line that connects them. The miracle behind everything else can happen only here — only here can things acquire meaning. If man wishes to escape from the untruth in which he is born, and in which he is destined to remain, he must tread that line, touch the water there and formulate a desire. In this way he will enter the vow , enter the hazardous state in which truth can be spoken, in which desire can be fulfilled, in which the gesture assumes a meaning. If every sacrifice is a “ship that sails toward the sky,” the two fires, āhavanīya and gārhapatya , will be the sides of that ship, the limits within which the pilot (each and every sacrificer) must move, from the moment in which he begins to carry out certain movements: those movements, if they take place between the two fires , acquire a meaning that separates them from the ebb and flow of human actions.

Читать дальше