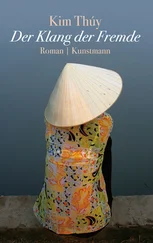

I had all of eternity because time is infinite when we don’t expect anything. And so I had decided on a stuffing with many kinds of roasted nuts and watermelon seeds that I husked by cracking the tough bark of each one very firmly. To avoid touching the delicate flesh inside required a lot of control to stop at the right moment. Otherwise, the flesh would break like a dream on waking. It was painstaking work that allowed me to withdraw into my own universe, the one that no longer existed.

Fortunately, there are no verb tenses in the Vietnamese language. Everything is said in the infinitive, in the present tense. It was easy, then, to forget to add “tomorrow,” “yesterday” or “never” to my sentences to make Luc’s voice ring out.

I had the impression that we had lived a lifetime together. I could visualize precisely the position of his right forefinger pointing up when he was annoyed, his body relaxed in the shadow of the shutters, the way he wrapped his long royal blue scarf around his neck when he was running after his children.

thẻ bài

dog tags

LUC’S ABSENCE HAD LED to the disappearance not only of himself and of “us,” but of a large part of myself as well. I had lost the woman who laughed like a teenager when she tasted the ten flavours of sorbet at the oldest ice-cream maker in Paris, as well as the one who dared to look at herself lingeringly in a mirror to decipher the reflection of the word written in felt pen on her back. Today, when I stand on a stepstool at the bathroom mirror, I can sometimes find the blurry remains of the letters ruoma if I read from the top of my spine to the bottom and amour in the opposite direction.

I don’t recall exactly how much time passed before Maman intervened. In the absolute dark of her bedroom, where she had asked me to spend the night, she put a small metal plate the size of a tea biscuit into my hand. It was one of the two dog tags belonging to Phương, the young boy who’d become a soldier and who had given her a poem when she was a teenager. The tags embossed with the same essential information about him had to be worn around his neck at all times, unless he fell on the battlefield and a comrade in arms pulled one off to take back to the base. Before he left, he’d gone to see her in uniform and given her the plate to offer her “the life he hadn’t lived” and his dream of her that would be eternally a dream if he didn’t come back to retrieve it.

For many years, every time Maman saw a military helmet abandoned by the side of a rice paddy or in some reeds, turned right or wrong side out, empty or filled with rainwater, she thought she would collapse from inside. If her feet hadn’t been obliged to continue advancing in her comrades’ footprints, she’d have knelt beside those helmets and never got up again. Fortunately, the silence of the single file kept her upright, for a false move could trigger a mine, endangering the lives of all those soldiers ready to stop the cannons from sliding down a muddy slope by lying in front of the wheels: sacrificing themselves for the cause of a nation.

hy sinh

sacrifice

WHEN SHE CAME BACK from the jungle, she went to find Phương, who lived in the family house with his aging parents and his child, who was still at his mother’s breast. He had become a doctor, a man respected and loved, according to the people in the village. She had observed him settle down for the noonday siesta in his hammock in the shade of the coconut palms. Bare-chested, shirt hanging on a branch, army chain still around his neck. She had watched him sleep and wake. She had expected him to get up when he moved his arm, but he had stayed motionless amid the rustling of leaves and the plashing of the tails of the carp in the pond. It was in that peaceful, everyday calm that she had noticed Phương’s hand hunt for the clasp on the chain wrapped with ribbon that she’d removed from her hair to give him on the night he left. The ribbon was not satin like those of her young half-sisters, because she’d had to create it by weaving and twisting very tightly the hundreds of bits of embroidery thread her stepmother had thrown out.

Maman made Phương’s head turn not by advancing towards him but by walking two steps away from him. She stood with her back to him until he left for his medical clinic. Out of love, she never returned.

ăn sáng

breakfast

NEITHER MAMAN NOR I slept that night. The next day, I fixed the children’s breakfast as I did every morning, as quietly as possible so as not to waken my husband, who preferred his mornings to be calm and solitary. I handed them their lunch boxes on the doorstep as I did every day, but that morning I sensed Luc’s hand stroking my upper back so that I would bend down to their level and kiss them, as he would have done if he’d been there, as he did with his own children every morning.

And two days later, I slipped a tiny note into their sandwich wrappings, the same one Luc wrote to me at the end of every message, like a signature: “I love you, my angel.”

Since then, I comb my daughter’s hair with the same movements as Luc, who cherished each strand of mine. In the same way, I apply cream to my son’s back, stroking the nape of his neck.

Then, one afternoon, with Julie by my side, I went to see the Vietnamese beautician who had told me that her clients claimed she had the power to thwart destiny and give them new fates by tattooing red beauty marks in strategic spots recommended by “destiny readers.”

yên lặng

silence

ON MY FIRST VISIT, I had a red dot tattooed at the edge of my forehead, a centimetre to the left of my nose. I made a second appointment for a second mark at the top of my inner right thigh on the day I needed a reason to look at the blue sky and wait to see the trail of a plane. The third time, it was in honour of the leaf of a Japanese maple found by chance between two pages of a dictionary that Luc had sent along with the ring we had chosen together. There was an interior garden in the jewellery store, home to the miniature tree. The owner had allowed Luc to take a leaf when he went there a month later to pick up the ring that had been adjusted to fit my finger. The fourth time, it was snowing very lightly. A large flake settled on the tip of my nose that morning, in the same place where Luc had taken another one away with his lips.

Those visits to the beautician allowed me to reproduce on my body those red dots of Luc’s that I knew by heart. I think that on the day when I have all those red dots tattooed, if I were to join them, I would be drawing the map of his destiny on my body. And maybe on that day he will show up at my door, take me by the hand as he always did instinctively, and stop me from saying “Disaster” as he kisses me.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

this page: From Cứa đã mở, Thơ by Việt Phương, 2008.

this page: Nguyễn Du, lines 1–8.

this page: Rumi, Bridge to the Soul , translator Coleman Barks. Copyright © 2007 by Coleman Barks. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

this page: Edwin Morgan, New Selected Poems , Carcanet Press, Manchester, 2000.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND THE TRANSLATOR

Читать дальше