“Would you agree to cook for my mother?”

cầm

chin

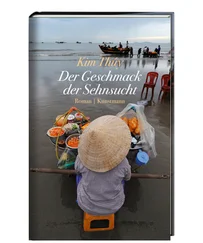

ON THE WAY HOME, Luc pointed to the poppies that coloured the edges of the highways. How could such a fragile flower inch its way through the wild grasses, defying concrete and asphalt? He explained to me that their appearance was deceptive, that poppies could sweep through uncultivated lands or attack a whole wheat field. A number of painters had been captivated by their cockscomb colour, but for Luc the poppy brought to mind Morpheus, who uses the flower as a magic wand. He just has to touch us gently with some petals for us to fall asleep and dream sweet dreams. As for me, I was living a waking dream where I dared not blink for fear it would all disappear. I discovered Monet’s Coquelicots at the Musée d’Orsay, and also the triangle of skin beneath my chin where Luc’s fingers had brushed against me to fasten and unfasten the buckle of the motorcycle helmet.

chợ

market

THE NEXT DAY, between two appointments for him and between two commitments for me, we went to the thirteenth arrondissement to go shopping with his children, who had the day off school. We zigzagged down the narrow lanes, amid baskets and boxes piled according to some obscure logic known only to the store. The children weren’t the least bit intimidated by the size of the crowd or by the din of foreign languages. They were comfortable bombarding me with questions: How do you eat a sapodilla? Where do dragon fruits grow? How many arms does an octopus have? Why are the eggs black? Their enthusiasm drove me to buy with no exception or hesitation everything that had roused their curiosity. Back at their grandmother’s place, we spread the fruit on the garden table before having her sit down with us. To our great surprise, she divided the custard apple in half before eating its milky flesh, spitting the black pits into her hand.

mãng cầu

custard apple

WHEN THE COMMUNISTS WON and the country was reunified, numerous families were reunited.

Many young people had fled the North by crossing the seventeenth parallel, which divided the country in two, leaving behind parents they found again twenty years later. The young people had become parents in turn and their children, little Southerners, knew nothing of the tradition among Northern women of coating their teeth with black lacquer, an operation that took two weeks of diligent work by a professional lacquerer and the same number of days of pain and discomfort. Jet teeth have been celebrated by the poets and considered one of the four criteria of women’s beauty. The dye lasted a lifetime and protected the teeth against any attack by food. Women wore the shiny black smile with pride until the tradition was eclipsed by elegance à la française . The disappearance of that cultural legacy was confirmed for me when I heard a child ask why his grandmother from the North kept the pits of custard apples in her mouth instead of spitting them out. The child couldn’t conceive that his grandmother had black-lacquered teeth and that she was one of the last representatives of a dying tradition.

I was pleasantly surprised, then, to see Luc’s mother scatter the pits on the table and try unsuccessfully to push one between two others. It was a game played by Vietnamese children who didn’t have marbles. I approached her to help continue the movement of her finger, which was refusing to obey her wishes. Luc came to play his turn and, finally, the children. Each one held on jealously to the pits he’d collected and the winner performed a victory dance as if it were the World Cup. They also tried to kneel on the skin of the jackfruit like Vietnamese students being punished, but they jumped as soon as they felt the scales.

While they were playing with wooden swords they’d found when leaving the store, I was caramelizing the fish above a battered, rusty old bucket filled with blazing coals that made it into a kind of grill. I was cooking outside, as they’d done at the orphanage, as is done at most houses in Vietnam. Luc’s mother came and sat on a stone beside me, taking the long bamboo chopsticks from my hands to turn the pieces of fish. Luc took her photo so he would never forget that act, which had been absent from his memory for the past twenty-five years. I prepared two portions, one not so spicy, for the children. On the other, Luc’s mother sprinkled pepper I’d crushed roughly in a mortar. While we had her attention, I whispered a lie: “The children at the orphanage are well. They can’t wait to see you.” I don’t know if she believed me, but she began stroking my hair again.

cải cúc

chrysanthemum leaves

I SUGGESTED THAT WE EAT at the children’s table to re-create the atmosphere of the street restaurants in Vietnam, where the customers sat on very low tables and stools. Luc’s mother was still in the habit of drinking broth with chrysanthemum leaves after the fish, at the end of the meal. For dessert, the children tried unsuccessfully to pick up cubes of mango with chopsticks. They challenged me, so I placed the pieces delicately in their mouths, which raised me to the rank of acrobat or magician. Luc tried to make them laugh by picking up a cube intended for them. His abrupt movement sent the cube flying and, instinctively, we both caught it in mid-air. I found myself one iota from his lips. Until that precise moment, I had never felt the desire to kiss anyone on the mouth. As well, when I kissed, I used my nose in the way that Vietnamese mothers do, inhaling the perfume of milk from their baby’s chubby thighs.

hôn

kissing

MY HUSBAND AND I didn’t exchange kisses as did other couples, either as a greeting or as foreplay. We were still modest, even after two children, even after twenty years of marriage. Language probably contributed to that restraint. We talked about things without naming them. It was enough to say “to be close” ( gần ) to understand that there had been sexual relations. My husband just had to turn towards me and I would understand my wifely duty. It was enough for him to be happy for all of us to be. Our marriage was uneventful, undramatic.

vô hình

invisible

MAMAN HAD TAUGHT ME very early to avoid conflicts, to breathe without existing, to melt into the landscape. Her teachings were essential for my survival, because she was sometimes called away on assignment. We rarely knew when she would leave and even less often when she would come home. While she was away, she sent me to stay with people she knew or who had been ordered to look after me. I learned very quickly to be at once invisible and helpful so that I’d be forgotten, so no one could criticize me, so no one could attack me. I knew exactly when I must set a plate down next to the mother who was on the point of taking the vegetables out of her wok without her seeing my hand, just as I could keep the porcelain filters filled with drinking water with no one seeing me empty the kettles that had cooled down during the night.

I could identify the needs of my foster families in one day, two at most. It was very easy for me, then, to anticipate my husband’s wishes before he was aware of them himself. I saw to it that his underwear drawer always held enough white T-shirts with no shoulder seams, a garment worn by certain working-class Chinese. From habit and nostalgia, he had continued to wear one under his shirt. I replaced the worn-out ones with new ones bought in a store in Chinatown without his realizing it because I washed them twice to soften the fabric, to make them his. Similarly, the ball drawer always had new tennis balls for his Wednesday and Friday game nights and more recently, golf balls for Saturday mornings. The advertising inserts were always removed from his National Geographic s because those pieces of cardboard irritated him particularly and pointlessly.

Читать дальше