Probably that is why Maman put a jade bracelet on me when I was still very young. At the time, I didn’t need to soap my hand or to squeeze my palm as do most women who choose to wear the stone, which some people claim is more precious than diamonds. Today, it surrounds my wrist without slipping because the bone has grown to fill the entire rigid circle. Barring some exceptional circumstance, that bracelet will follow me to my final destination. In the meantime, it is my aide-mémoire because it doesn’t absorb the heat of flames and is never scratched. It reminds me to be solid and, above all, smooth.

yêu

love

I HELD THE BRACELET tightly like a lifeline during my sleepless night, because I was dizzy at having accepted Luc’s invitation to see him the next day and also to hear him play clarinet that same evening, without hesitation, without Francine, without fear. I followed his voice just as my grandfather had followed the traces of my grandmother, two people who had never known me.

Maman told me that this father, who sounded strict, had asked to be buried with a ceramic jar that he kept with great care in his cupboard. It contained some earth he’d taken from the footsteps of his wife the first time he’d seen her. He had used a leaf of a plane tree to take the entire print in one go. His hands were shaking because he had come close to never finding her. A soccer match that had gone overtime made him miss the first appointment, arranged by the matchmaker. He had arrived an hour late to a closed door and some deeply offended people. He had left with no regrets, until the moment when he saw my grandmother’s conical hat cross the barnyard. It was a hat like any other, the kind worn indiscriminately by women and men of all ages: ivory, slightly worn, the summit pointing skyward. Yet the strip of cloth on hers, which went under her chin to keep it in place, had ties that hung down on either side. These strips seemed to react differently to the wind, which rendered the hat remarkable and her, his future wife, unique.

In my case, it was Luc’s hand straightening Francine’s collar over her scarf when he came to say hello. It was his twisted face on stage and his bursts of laughter with his musician friends in the light of bare bulbs. Or maybe it was nothing in particular.

thang

staircase

LUC HAD CLIMBED the four floors two steps at a time and arrived at my door instead of being announced by the hotel’s reception desk. That morning, he had texted me: “Do you know the word apprehension ?” I didn’t know the meaning of the word and didn’t know that I was already inhabiting it.

There are words whose meaning I try to deduce from how they sound, like colossal, disconnect, apostil , others by texture, smell, shape. To grasp the nuances between two related words, to distinguish melancholy from grief, for example, I weigh each one. When I hold them in my hands, one seems to hang like grey smoke while the other is compressed into a ball of steel. I guess and I grope and the answer is as often the right one as the wrong. I constantly make mistakes, and until now the most surprising had to do with the French word rebelle , which I thought was a derivative of belle : to be belle again, because beauty is acquired and then lost. Maman often told me that in case of conflict, it’s better to hold back than to insult someone, even if that person is the one at fault. If we taint the other, we soil our mouth, because we must first fill it with anger, blood, venom. Starting then, we are no longer beautiful. I thought that the re in the word rebelle opened the possibility of a redemption, the one that would let us regain our beauty from before.

I was often wrong, so that time I dared not guess the meaning of the word apprehension . I only felt fear when I opened the door to my room.

mặt trăng

moon

HE STOOD IN THE hotel corridor for several breaths before he knocked. In one hand he was holding a coat and in the other, two helmets. Still today I try to remember his first words, in vain; at that precise moment, I was probably somewhere else, maybe on the moon. Vietnamese mothers tell children that a woodcutter lives there, sitting under a banyan tree, playing a flute to entertain the moon fairy. Chinese women show the shadows that form the silhouette of a rabbit preparing the recipe for immortality; Japanese women sew for their daughters hagoromo , feathered robes like those worn by the fairy who has departed the Earth for the Moon, leaving behind her a besotted emperor. He asked his army to take him to the summit of the highest mountain so that he could be closer to her.

Luc took me into those fairy tales by covering me with his down coat, its sleeves coming down to my knees. “I beg you, please don’t protest,” he said, bending down to do up the zipper. I locked the door behind us with the vertigo of an astronaut. I’d read that they sometimes suffer from vertigo in space because they lose the notion of up and down. Worse than that, I had also lost left and right.

thoát

freed

I CLIMBED AWKWARDLY ONTO the scooter behind him and we drove across Paris to his mother’s residence. She wasn’t expecting us. She no longer expected anyone. She didn’t sing now and didn’t care about the person she saw in the mirror. I wondered if she was approaching the state of nirvana, where the soul quietly leaves the body, free of all desire, insensitive to all suffering. Just as Luc was asking me if I was frightened, she placed her hand on my head and started to stroke my hair, slowly, constantly. All around, the walls were covered with photos, including one of her in a bright red T-shirt with a royal blue heart on the chest, sitting at the piano with, in the background, dozing children temporarily freed of their lame bodies.

mồ côi

orphan

HER HANDS WERE WEAK NOW, but they still expressed so much gentleness, perhaps because her gnarled fingers had written hundreds of letters to her orphans, never discouraged though she had yet to receive a reply. All through his childhood, Luc had to share his mother with those ghosts that haunted her. At first, she stopped every Vietnamese woman she ran into on the streets of Paris to ask if she knew the orphanage. If by misfortune the person had lived in the same district, she would be invited over and asked a thousand questions. One day, a lady had told her that the house had been confiscated and redistributed to five families. The children had been chased away when the property was first being divided. Before the lady could describe the silence that reigned in the neighbourhood during the operation, Luc’s mother had stood up from the table. As of that day, she had refused to speak to any Vietnamese, for fear of encountering another one who would confirm the dark destiny of the children. She had also kept Francine and Luc away from possible contact with them.

cá kho

caramelized fish

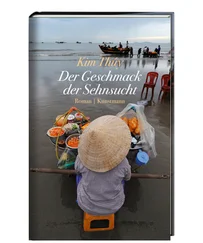

FRANCINE CAME TO ME excitedly, like a little girl disobeying an outmoded and emotionally restrictive prohibition unjustly imposed by her mother. The week before we first met, in the window of her local bookstore, the cover photo of La Palanche —a terracotta bowl half sunk in embers and containing a caramelized fish steak — had moved her to tears. The aroma of fish sauce had struck her as if she were still standing in the kitchenette of the orphanage just as the cook was pouring some into the piping hot mixture of sugar, onion and garlic. That same day, Francine had given the book to Luc. Like her, he had smelled immediately that violent and inimitable aroma that their mother preferred to any other. She fixed that dish at least once a month, with blanched cabbage or sliced cucumbers and steamed rice. As soon as he was able, Luc escaped from the house when cá kho tộ was being prepared. He didn’t know which he hated more, the smell of cooked nước mắm or the atmosphere surrounding this dish that was so heavy with obsession and dependence.

Читать дальше