Most Vietnamese believe in the existence of wandering souls who haunt life, who watch for death, who stay wedged between the two. Every year, in the seventh lunar month, people burn incense, paper money and garments to help the ghosts to free themselves, to leave the world of the living, which has not anticipated a place for them. When I threw the false paper money, orange and gold, into the fire, I hoped for both the ghosts and Maman’s sadness to disappear, even if she denied the ghosts’ existence with the same fervour as the Communist Party, which condemned the people’s fear of those roving spirits, unidentifiable and with no witnesses.

It’s true that Maman’s face, like my husband’s, showed neither pain nor joy, to say nothing of pleasure, while I could read everything on Julie’s. When she wept, full of affection, at the birth of my son, her heart was drawn on her cheeks, her forehead, her lips. In the same way, she was moved when she carried children just arrived from faraway lands to greet their new destiny in the cocoons carefully woven for them in Montreal. She took their photos and gave them greeting cards signed by her friends in the adoptive parents’ group. She was the first to say, “I love you,” to my baby who was still curled up in my belly. She was also the one who took my husband’s hand to place it against the little foot that was imprinted on my stretched skin. Then, despite his stiff body language, she was quite ready to take him in her arms when he agreed to sponsor Maman for her immigration to Canada.

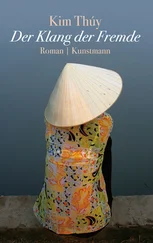

Đông-Tây

East-West

IT TOOK SEVERAL YEARS and countless photos of my two children to persuade Maman to join me. Unlike my boy, my little girl arrived very quickly, at the same speed as the multiplication of catering orders for private and corporate parties. My husband had bought the duplex next door to enlarge our living space. At the same time, Julie was building a large kitchen under the workshop and she turned the two apartments above us into a daycare for her daughter, my children, and now and then the children of friends who found themselves without a sitter. Two ladies from the Philippines took turns helping out during parties that ended too late or mornings that started before dawn.

In the kitchen, Julie had hired Philippe, a pastry chef, to reinvent Vietnamese desserts, because our traditions regarding cream, chocolate and cakes were limited to a few, very basic recipes. As a matter of fact, Vietnamese call birthday cakes bánh gatô , with bánh meaning “bread-cake-batter.” We had to import the word gatô because cake comes from a singular culinary tradition. We had to learn how to use butter, milk, vanilla, chocolate — ingredients that were as foreign to us as the cooking methods. Lacking ovens, Vietnamese women baked their cakes in a cauldron covered with a lid on which they placed chunks of blazing coal. The cauldron was set on a terracotta barbecue the size of an average cachepot so the mixture could be elevated and baked without burning even if the temperature couldn’t be constant or the heat distribution uniform. I was very surprised, then, at Philippe’s thermometer as well as his stopwatch and his set of measuring spoons, not to mention implements as mysterious as they were impressive. I ran my hand over the contents of the drawers and shelves with the fascination of a child stepping into a cockpit.

Slowly, Philippe brought me into his world. He started with hazelnuts, plain, roasted, whole, ground — because I adore nuts. From Chinatown, I would bring him pandan leaves to share with him their intensely green colour and their scent: in Thailand, taxi drivers place a fresh bouquet under their seat every two or three days. As Philippe was already familiar with lychees, I offered him their cousins, longans, whose glossy seeds often serve as a metaphor for a pretty girl’s eyes, and rambutans, with their red peel and hairy surface like a sea urchin, but soft to the touch.

My Vietnamese-style banana cake was delicious, but it looked frightening, sturdy and uncouth as it was. In no time, Philippe softened it with foamy caramel made from raw cane sugar. Thus he married East and West, as with the cake with whole bananas fitted into baguette dough soaked in coconut milk and cow’s milk. Five hours’ baking at a low temperature forced the bread to play a protective role for the fruit as the bananas slowly delivered up the sugar in their flesh. Anyone lucky enough to taste that cake freshly baked could see, when cutting it, the crimson of the bananas embarrassed at being caught in the act.

màu

colour

PHILIPPE ENHANCED AND ENNOBLED the desserts that the Vietnamese call simply by the number of colours in the ingredients: chè three colours, chè five colours, chè seven colours. Each merchant has her own interpretation of the dessert, which is usually eaten as a snack on the sidewalk at a corner, sitting on a small stool when school lets out, or between two destinations with friends. I think that meeting someone for chè usually means a date in a café, except that there it’s made with blends of mung bean paste, tapioca in the shape of pomegranate seeds, red beans, black-eyed peas or the fruit of the nipa palm, all topped with a mountain of crushed ice. A good many secrets were shared between two spoonfuls of chè and a good many love affairs were born in that place, which often had no address.

In our workshop, when they tasted Philippe’s creations, the clients’ confidences scented the air, and sometimes they kissed passionately as if they were alone, set back from time. I had never seen people so much in love so close up before. Nor had I ever heard “I love you” spoken aloud, as Julie did every day. She never hung up the phone without saying “I love you” to her husband and her daughter. I sometimes tried to put into words my gratitude towards Julie, but I was never really successful. I could only show my affection through everyday acts, such as preparing for her, during her numerous appointments and before she even felt the urge, the lime soda she adored, or by unplugging the phones in her office when I made her take a fifteen-minute nap, or by rubbing a turmeric root on a freshly healed sore to prevent it from scarring. I thanked heaven when I had the chance to look after her daughter for five, seven or ten days so she could join her husband in Turkey, Japan or Sri Lanka. I could offer her only my friendship, because Julie lacked nothing, she had so much to give and she gave everything to everyone. She was a merchant of happiness.

mùa

season

THEY SAY THAT HAPPINESS cannot be bought. What I learned from Julie is that on its own, happiness multiplies, is shared, and adapts to each of us. It was within that happiness that the years accumulated one after another, paying no attention to calendar or seasons. I could not say at what moment exactly Hồng took the helm of the restaurant kitchen. I only know that, very early one morning, I opened my eyes and saw a world so perfect it made me dizzy. Beside me, my husband’s face was pressed into the pillow, rested, peaceful, and wrapped in a nearly palpable film of calm and stillness. In the adjacent rooms, my children were fast asleep. I had the impression I could hear their dreams, where even the monsters seem playful or are transformed into gentlemen. Maman had chosen her domain at the end of the corridor joining the two apartments. She involved herself in the children’s homework as rigorously as a substitute teacher. I often caught her smiling discreetly when they called her Bà Ngoại , maternal grandmother. During school hours, she insisted on helping Hồng in the kitchen and refused to join the Vietnamese community seniors’ club.

Читать дальше