Their story covered many years and it was that Mayn spent too much time away. It even once got called that — a cover story; she’d said it to him in a letter while they were still married. (He remembered it when he took his daughter out to dinner some years later, she wanted him to sign a petition to get a Philippine writer out of jail. Jail? It might as well have been the Death House!)

He knew a handout. Some of his work was taking press handouts off a counter or desk in a busy room as far away as it was familiar and nondescript, handouts that were sometimes little more than a friendly pitch Xeroxed off an electric typewriter hustling a product (this was the point), and a newsman could put these handouts on the wire more or less condensed. But he would also go after assignments where you didn’t get a handout because what there was to peddle, to get onto the wire, wasn’t immediately clear, though he didn’t believe in what wasn’t clear, and he kept after the briefing officer of a natural-gas company who would turn away from figures like 7.5 trillion barrel-miles of various gas liquids and anhydrous ammonia being carried through more than two thousand miles of pipeline in 1961 to the claim that this firm was a "future" firm operating in a frame of reference not less than Energy itself and Related Earth Resources, and how can you be anti-Energy? you might as well be anti-American. Joy understood what he tried to do and liked him for it.

In May of ‘60, no longer working for AP, he did with the government story on the overflights what the story did, or said to do. With itself, that is.

Routine report: pass it on.

Mayn was like any company man or stringer.

So Powers, the pilot, was photographing weather — or (like a mechanical part of him) the plane was photographing weather; and the flights over Russia were routine weather observation — NASA said so. Now Mayn knew — or figured — that the story wasn’t true, and he had heard that it was not true from people who ought to know but also from a man he didn’t like named Spence for whom the extreme altitude of the slender U-2 plane gave to it, gave to the plane’s glinting eye, an exponent of threatening force, a light too powerful to see with the naked eye unpeeled.

Ray Spence was far away but approaching Mayn in the form of Mayn approaching him — that’s what Mayn felt. Well, people weren’t always credible.

Spence told Mayn back a story Mayn had told him about the newsman who got the jump on everyone else at the explosion of the Hindenburg. Mayn mentioned this — that Spence had told Mayn back his own story — and Spence laughed, but too long and softly as if it was understood Mayn had made a curious joke. "How’s the family newspaper?" he then said. "Got any good numbers in your book?"

But the government overflights story which everyone knew wouldn’t stick made Mayn, who was fed up with words within words, curious instead about the weather. What had NASA to do with weather and what was there to know?

So he was in Florida and later he was in California. Not into space he said — not space, not science — not ESP — and you could throw in the Fourth Dimension (and he didn’t mean the bar in Brussels of that name for he had a quizzical way of showing off or the book store in Dallas). Weather satellite — that was the size of it. No, not science — as Joy should know, who knew him.

You called the satellite a grapefruit. And all he was seeing was exactly how a four-pound grapefruit covered cloud belts across a quarter of the Earth. Then talking to the Coast Guard. Aboard a white weather ship about to leave for the Bermuda Triangle. Tall, thin meteorologist in the weather shack up on the boat deck facing aft, a Texan (‘‘originally"), with a German uncle in Chile multiplying bees. A German grammar on a folding chair on the rolling deck. A man in khakis with a bad black Texas mustache, no kidding, and an unconvincing habit of in the middle of his talk to Mayn calling out, loud and jolly, to any kid who came by with a wire brush or an electronic technician’s tool kit, then one who materialized below on the quarter-deck photographing a huge seagull standing on the rail. A global network of weather stations. Mayn could get into that. The man with the mustache lent him a manual which Mayn read and forgot about and later decided not to mail back from New York after the cutter had put out for weather station. This global network looked so compact, but put yourself in it and your neighborhood is endless. This thought followed him, not he it.

Up?

The curvature of space he would leave to other minds than his.

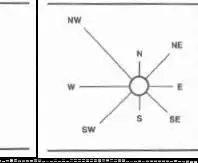

He talked to Joy about the weather. So then he’d be unable to explain his interest in it. That is, to her — at least when she said, "But blue sky in the winter in New York — but in Chicago over the lake, you’ve never seen how the water goes up the sky, it attracts the horizon, it lifts it, my father used to say — why, meteorology — what do these guys know?" ("I know, I tow," said Mayn.) "What about rain against the window—" ("Don’t be an idiot, Joy.") " — against the window the summer we were at the Cape playing Monopoly?" "Look, Joy": he drew her a wind rose:

"The length of the line shows how often you get wind from that direction — during the year, let’s say. And in another type of rose the lines thicken so you see how often the wind was strong or light or moderate." He drew her one of these, too.

"All right, I can see it," she said.

"Helps them decide where to put airports and buildings and vegetative wind screens and factories that smoke up the air. The wind rose shows the horizontal motion of the atmosphere. Now you know all that I know."

She laughed at that, and she didn’t give in. "What about the wind hitting us when the car got past the mesa cliff driving down to Albuquerque, remember how red the cliff was? wasn’t it near the Continental Divide?"

Have to ask a lot of a woman, he knew she was telling him to think. He asked her to please shut up. The one long car trip they’d taken.

And when they had a discussion about the check he’d taken from her checkbook and she said he was a shit but gave it a tired, unimportant sound he didn’t like, he told her that she was really thinking about his being away but, hell, he could be talking about the upper air with the Coast Guard and the civilian meteorologists just as well in Boston or Portland but he was talking with them here at home in New York.

He’d already talked to them in Florida, she said — and, home? she said. Maybe home for him — which made him laugh like the — yes, strangely like the — white pilot balloon ("pibal") that lifted for a second out of his mind complete with information on expansion and air resistance that was safely in his pibal notes — yet what she said stopped him. For wasn’t it her story that he was away from home all the time? But one day he saw (like a — like what singly neither had the words for). . saw like a resilience that the story was his story as much as hers, even if he would claim he’d never been wanted by the FBI like the man who among other things had actually bounced a check on the East Bank of the Mississippi which, granted, was real — that is, a snug, bright blue tavern north of Orion, Illinois, and just below Rock Island he recalled, where the river turns nearly west and the banks are south and north (whence come AP dispatches from the Chicago office to small member papers and radio stations). He pops a joke, but Joy is not put off her track, she goes to the bedroom passing the bathroom doorway through which a child can be seen sitting leaning forward on the John, a child whom the father also sees when he follows his wife angrily, who then brushes past him and leaves that bedroom passing again the bathroom doorway and the child who looks up at her and at the father. Elsewhere in time the decks of D-Day ships snap down into troughs like crevasses blown out by the Sicilian storm and as the decks drop down the silver bags of the barrage balloons snap their cables and rise up, up, so high the sound of the bag exploding is very hard to hear, isn’t it? Sometimes he couldn’t recover her face when he was away from home. Only her whole presence, watching him by just living, by being in a next room drying the lettuce or turning from a child to turn a page of the evening paper — to see anything, to skim some news — to check the horoscope, hers first, but his second, though she disliked horoscopes. He loved her; he could say it to himself and honestly tremble while at the same time he recalled her needling voice after him. "I see you going in in the first wave with your big helmet over your eyes, a gun in one hand and a pencil in the other." What’s a gun? You mean a pistol? a rifle?

Читать дальше