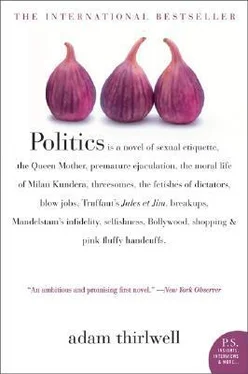

Adam Thirlwell - Politics

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Adam Thirlwell - Politics» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Politics

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Politics: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Politics»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Moshe loves Nana. But love can be difficult — especially if you want to be kind. And Moshe and Nana want to be kind to someone else.

They want to be kind to their best friend, Anjali.

Politics

Politics — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Politics», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Oh Nana, if only things were so simple. If only, just for now, Moshe possessed the necessary calm. But he did not. Instead, Moshe was theatrical. He was theatrical at heart.

Nana’s boyfriend was two emotions. Neither was useful. As outlined above, their common element was hysteria. Moshe was scared and ashamed. He felt ashamed because he had failed her. He had not been a believable fantasy. He was not realistic. And because he thought he had failed her, he also believed she was angry. She must be. And this scared him, because he thought that, due to her anger, she might be sarcastic, or frustrated. This made him particularly scared because if Nana was truly frustrated then he would feel even more ashamed.

On balance, then, he was more ashamed than scared.

But Nana, not sarcastic, not frustrated, was all solicitude. She was friendly and undismayed. ‘Are you okay?’ said Nana.

She is all solicitude! The girl is worried! worried Moshe.

His reaction, however, was simple. He improvised a persona of calm success. Everything, he decided, had gone well. Moshe was an assured seducer. First an astonishing sexual procedure had taken place and now, as they lay there, fulfilled, he decided to woo her all over again, telling her the secrets of his damaged unconscious. It was what people had sex for — the afterwards, the quiet intimacy, the talk.

This was a night to remember. Christ, yes.

Moshe did not answer Nana’s question. He did not describe his mental and physical state. Well, not directly. He gave her a small lecture.

With his eyes averted, because that was a gesture of — no, not embarrassment — sincerity, Moshe said: ‘Once I was with my parents in a small restron somewhere in Normandy. And from the window I saw this kind of mock- up of the Liberation, with a repro army marching through the streets.’ But, and this was the thing, it could also have been the occupation. Maybe they were miming the occupation, said Moshe. Because somehow he could also see a chateau at the top of the village and blond men in dry- cleaned uniforms moving slowly, and a minuscule Moshe somehow or other mixed up in the whole affair.

And that was it. That was his contribution to the catastrophe — an anecdote of miniature Moshe, a secret fear, a novelty.

What was Moshe trying to say? I will tell you. He was trying to say he was sorry. He was asking Nana not to be angry. He was trying to make her pity him. He was saying that Moshe was scared of the Nazis.

But Nana was not angry. She was not a Nazi. She was just confused. She wondered if Moshe was embarrassed. She wondered what other explanations there could be for this set-up — Moshe the conversationalist in bed, telling her about his childhood fears, surrounded by sex aids.

Nana’s arsehole was aching where Moshe’s fingernail had scratched her. This made her wriggle. She tried to get comfortable. She wondered how far Moshe had got inside her arsehole before he. She wondered did this mean she was now infected.

He could see her looking at him — naked, on his back. He was exposed. Moshe worried that Nana was looking at his belly, and looked down and there was his penis. His penis looked silly and slick. It looked depressed. So he got up to find some clothes. It was only nine in the evening, but all he wanted was his pyjamas.

Moshe returned to his travesty of Jewishness. He said, ‘Did you not like the Joosh thing? It was the best I could think of.’

Depressed, Moshe grinned.

She was looking at him, quiet. He was a comic visual diversion. ‘What?’ he said. And she grinned. She said, ‘Cherub, you’re only half Jewish.’

Moshe was standing in front of her with his body swaying slightly forward. He was resting his weight on his right leg, which was by now tartanly pyjama’d. The foot of his left leg was advanced a little. And his knee was gently bent. He was getting into his pyjamas.

Nana was wondering why she was happy, lying there as the street lights switched on, unequally.

‘And you’re not even circumcised,’ she said.

‘Let’s not squabble,’ he admonished her, as he hopped across the room in search of the left pyjama leg.

2. The principals

1

This has gone far too far. I can see that.

Before this experiment with anal sex and bondage, Moshe and Nana met and fell in love. After that happened, but before the anal sex, they also tried the missionary position, ejaculation on Nana’s face, oral sex, use of alternative personae, lesbianism, undinism, the threesome, and fisting. Not all of these were successful. In fact, few of these were successful.

In case this list worries you, perhaps I should explain. This book is not about sex. No. It is about goodness. This story is about being kind. In this book, my characters have sex, my characters do everything, for moral reasons.

After they fell in love but before they experimented with lesbianism and the threesome one of them fell for another girl.

By the end of this story one character will be dying from a brain tumour.

If only things were as simple as they looked. If only events occurred without a backstory.

2

So this was the beginning and the rest of it.

It was a play.

Her Papa had taken Nana to a one-off revival at the Donmar Warehouse. The play was Oscar Wilde’s Vera, or the Nihilists. It was the opening production, explained Papa, in a tribute week of Oscar Wilde’s complete works. This week had been crafted by the famous political playwright David Hare. It was designed to show that Oscar Wilde was our contemporary. He was twenty-first century. A homosexual man, Oscar understood that politics was everywhere.

Papa was on the board of the Donmar Warehouse, and so he had to see it. It was his job, he said. He had no choice. And he did not want to see it on his own. He wanted to see it with Nana. He said it was a treat. This was, he pleaded, a contemporary revival. David Hare had called the play a classic.

But it was not David Hare who persuaded Nana. No. It was Papa. She went because she loved him.

I should explain something here. Papa was a widower. Nana’s mother had died when Nana was four. And Nana’s mother is absent from this story. This is because she was also absent from the relationship of Nana and Papa. She was calmly absent. Nana simply saw her as Papa’s best friend. Whenever Nana imagined her mother, she imagined her chatting to Papa. And Nana did not want to interrupt these conversations between her mother and Papa. She preferred the conversations to carry on without her.

That was why Nana and Papa were such a duo. It is why they went, as a couple, to Vera, or the Nihilists.

And that was the beginning, Nana used to think, later. That play was the beginning.

As the lights undimmed, privileged Papa took Nana behind the scenes. And there Moshe was, straddling a plastic chair, admitting that he was the, yes, the star of the show. But he was tired of it all. He was tired of all the schmoozing.

Moshe was an actor.

The first time Nana saw him was on stage — backlit, melodramatic. Except — she teased him later, when they were in love — she hadn’t really seen him. Nana had almost dozed. She was bored by Oscar Wilde. Instead, she had looked round — at the lighting rig, the showy couple fingering each other on her left. She was annoyed by her bench-seat’s straight back, the stifled coughs behind her.

So that was why when Moshe — the actor who had played Prince Paul Maraloffski — stood up afterwards, backstage, and grinned his Princely grin, she did not notice the allusion. All she saw was a patch of tartar on Moshe’s front two upper teeth. One eye was oddly smaller than the other.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Politics»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Politics» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Politics» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.